HIV/AIDS ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus, spreads via certain body fluids; specifically attacks the CD4, or T cells, of the immune system; and uses those cells to make copies of itself. CD4 cells, also called helper T cells, are a class of white blood cells that help other lymphocytes (memory B cells) that are responsible for producing an antibody to fight infection based on stored data following past exposure to the antibody. As time passes, the virus can destroy enough of these specialized cells that the immune system no longer is able to fight off infections and disease.

HIV is unique among many other viruses because the body is unable to destroy it completely, even with treatment. As a result, once a person is infected with the virus, the person will have it for the remainder of their life (CDC, 2022b).

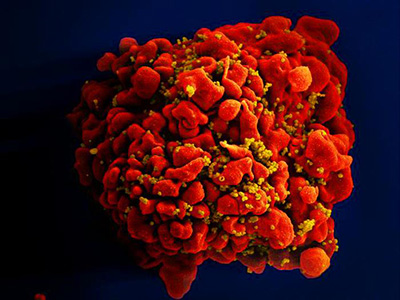

A single T cell (red) infected by numerous, spheroid shaped HIV particles (yellow). (Source: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2012.)

After the initial infection and without treatment, the virus continues to multiply, and over a period of time (which can be 10 years or longer), common opportunistic infections (OIs) begin to take advantage of the body’s very weak immunity. When an opportunistic infection occurs, the person has developed acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Today, OIs are less common in people with HIV because of effective treatment (CDC, 2021a).