RISK ASSESSMENT

The purpose of assessing the risk for developing pressure injuries is to implement early detection and prevention measures. This is of utmost importance, as assessment without intervention is meaningless in the effort to prevent a pressure injury from developing.

Risk Assessment Schedules

The skin is the largest organ in the body, and the clinician must assess it regularly. The assessment of pressure injury risk is performed upon a patient’s entry to a healthcare setting and repeated on a regularly scheduled basis (per facility policy) as well as when there is a significant change in the patient’s condition, such as surgery or a decline in health status.

A schedule for reassessing risk is established based on the acuity of the patient and an awareness of when pressure injuries occur in a particular clinical setting. Recommendations based on the healthcare setting are included below (WOCN, 2022a; Baranoski & Ayello, 2020). A particular facility or setting may have different regulations.

ACUTE CARE

Generally, pressure injuries can develop within the first two weeks of hospitalization, and older adult patients can develop pressure injuries within the first week of hospitalization. The initial assessment is conducted upon admission and repeated:

- At least every 24 to 48 hours

- Whenever the patient is transferred from one unit to another

- Whenever the patient’s condition changes or deteriorates

- Per facility policy

Most medical-surgical units reassess at least daily.

ICU/CRITICAL CARE

Intensive care unit (ICU) patients are at high risk for developing pressure injuries, especially on the heel. ICU patients have been shown to develop pressure injuries within 72 hours of admission. Pressure injuries have been associated with a two- to fourfold increase in the risk of death in older people in the ICU. Pressure injury assessment is to be done at least once every 24 hours (WOCN, 2022a; Baranoski & Ayello, 2020).

PRESSURE INJURIES AMONG CRITICALLY ILL PATIENTS

In a study of factors that placed critically ill patients at the highest risk for developing pressure injury, the presence of diabetes mellitus was found to be the predominant risk factor. In patients with serious healthcare-acquired pressure injuries (HAPIs), almost 30% had diabetes mellitus.

Mechanical ventilation was found to be the most frequent treatment-related risk factor, with the use of vasopressor agents second most frequent. These latter two findings indicate that diminished tissue oxygenation and blood supply are directly associated with pressure injury development. In the United States, respiratory failure necessitating mechanical ventilation is the most widespread cause for admission to intensive care units.

The most frequently occurring type of pressure injury among critically ill patients was found to be deep tissue pressure injury (DTPI).

Two other major findings from the study were that adherence to the implementation of preventive practices decreased the development of HAPI among critically ill patients. Secondly, there is a need to develop a pressure injury risk assessment tool that captures the existence of numerous concurrent conditions in critically ill patients, which are specific risks for pressure injury development (Cox, 2022).

INPATIENT REHABILITATION SETTINGS

The presence of a pressure injury was significantly associated with lower gains in motor function, longer length of stay, and decreased odds of being discharged to the community. Data from one study indicated that 51.1% of patients with spinal cord injury acquired at least one pressure injury during their first rehabilitation stay. Multiple risk factors were identified for the prevalence of pressure injuries in this population, including the severity of the spinal cord injury, development of pneumonia, and longer lengths of stay (Najmanova, 2022). Assessment is on admission and per facility protocol.

LONG-TERM CARE

Nursing home patients are at high risk for the development of pressure injuries. In long-term care settings, most pressure injuries develop within the first four weeks.

- In skilled nursing facilities, initial assessment is conducted upon admission and repeated weekly thereafter.

- In nursing homes with long-term patients, assessment is conducted upon admission, repeated weekly for the first month, and repeated monthly thereafter, or whenever the patient’s condition changes.

Among nursing home residents, it has been found that there is a substantial connection between the occurrence of pressure injuries and the presence of dementia, cerebrovascular disease, and female sex (Elli, 2022).

HOME HEALTH

In home healthcare settings, most pressure injuries develop within the first four weeks. The initial assessment is conducted upon admission and repeated:

- At resumption of care

- Recertification (assessment and approval of the need for continuation of patient care)

- Transfer or discharge

- Whenever the patient’s condition changes

Some agencies reassess with each nursing visit.

An important factor in preventing pressure injury development in the home care setting is the education of family and caretakers about interventions needed to maintain skin integrity. This must be an ongoing process and frequently evaluated by the clinician (Wound Source, 2019).

COMMON QUESTIONS ABOUT PRESSURE INJURIES

Q: Can a pressure injury be treated at home?

A: Yes, pressure injuries can be treated at home after they have been diagnosed by a healthcare provider and a plan of care is put in place. This may include help from a home care clinician who is skilled in wound care and who will educate the patient, family, and caregivers in dressing changes, patient repositioning, and other strategies to assist with wound healing.

HOSPICE AND PALLIATIVE CARE

One study showed that of eight pressure injuries that developed during the study, five occurred within two weeks prior to death. Assessment occurs at admission and as patient condition changes. The development of pressure injuries during the end-of-life phase can significantly increase pain and suffering (Seton, 2022). However, preventing pressure injury development at the end of life can be challenging. Skin care must focus on hygiene, promoting comfort, pain control, and limiting distressing symptoms such as wound drainage, bleeding, or odor (Vickery, 2020).

Elements of an Assessment

Prevention of pressure injuries must begin with frequent and routine assessment of the patient’s skin and of the risk factors that, if left unmanaged, will contribute to the development of an injury. Risk assessment without interventions to modify the risk is meaningless.

A head-to-toe, front and back inspection of the skin must be done on admission and at least daily (or per facility regulation). Five parameters for skin assessment are recommended by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services:

- Skin color

- Skin temperature

- Skin texture/turgor

- Skin integrity

- Moisture status

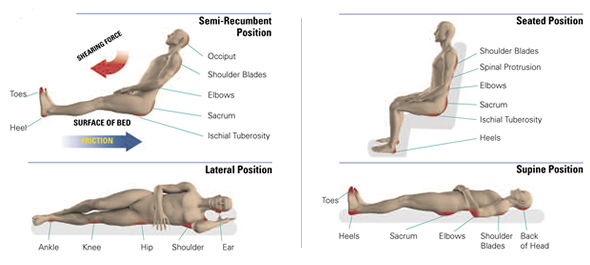

The assessment focuses on high-risk areas such as bony prominences, areas of redness, and under medical devices. The specific areas to assess are shown in the table and diagram below. The assessment must not be limited to a visual inspect of the skin surfaces but also include tissue palpation to determine skin temperature, presence of edema, and overall tissue uniformity (WOCN, 2022a).

| If the patient’s position is: | Then focus on these areas: |

|---|---|

| Lateral | Ear, shoulder, trochanter, knee, ankle |

| Supine | Occiput, shoulder blades, elbows, sacrum, heels, toes |

| Semi-recumbent | Occiput, shoulder blades, elbows, sacrum, ischial tuberosities, heels |

| Seated | Shoulder blades, spinal protrusions, elbows, sacrum, ischial tuberosities, heels |

Bony prominences are high-risk areas for pressure injuries. (Source: © Invacare Corporation. Used with permission.)

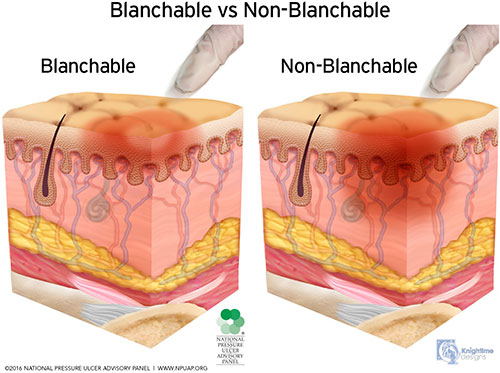

Blanchable erythema is a reddened area that temporarily turns white or pale when pressure is applied with a fingertip. This is an early indication to redistribute pressure. Nonblanchable erythema is redness that persists when fingertip pressure is applied. It means that tissue damage has already occurred. (See image below.)

It can be difficult to identify skin problems in patients with dark skin. Redness may not be easy to see. The clinician needs to compare the at-risk area (such as the coccyx or hip) with skin next to it and look for color differences or changes in temperature or pain (WOCN, 2022a).

Blanchable vs. nonblanchable erythema. (Source: © NPIAP, used with permission.)

ASSESSMENT AND MEDICAL DEVICES

Medical devices such as shoes, heel and elbow protectors, splints, oxygen tubing, face masks, endotracheal tube holders, compression stockings and TED hose, and others must be removed and the skin inspected daily. For example, oxygen tubing can cause pressure injuries on the ears, and compression stockings and TED hose have been known to cause heel injuries.

If the device cannot be removed—such as a nasogastric (NG) tube, urinary catheter, tracheostomy holder, neck brace, or cast—then the skin around the device must be carefully inspected: the nares for an NG tube, the neck for a tracheostomy, the mucosa for a urinary catheter, etc. If the patient complains of pain under an unremovable device, the physician is notified (WOCN, 2022a).

Consider all adults with medical devices to be at risk for pressure injuries.

- The Joint Commission Quick Safety defines a medical device–related pressure injury (MDRPI) as an event that results from the use of devices applied to patients for diagnostic or therapeutic reasons (TJC, 2022). Studies indicate that as many as 50% of HAPIs are associated with medical device use (Sermersheim, 2021).

- The most frequently used medical devices that cause pressure injuries in adults include those related to respiratory care, tubes and drains, braces, compression wraps, and splints (Pittman, 2020).

- The most commons sites for MDRPIs are the ears, nose, face, chin, and lips (Brophy, 2021).

- Among pediatric patients, the prevalence of MDRPIs has been reported to be as high as 70%. This population is at high risk for serious injury related to medical devices due to factors such as immature skin development (especially in the neonate population), the lack of availability of correctly fitting medical devices, and the use of attachment and immobilization products (Stellar, 2020).

Injuries caused by medical devices are reportable to state and federal agencies, just as are those caused by pressure on bony prominences (EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

ASSESSMENT AND MOBILITY

Immobility is the most significant risk factor for pressure injury development. More frequent monitoring to prevent pressure injuries is conducted for patients who have some degree of immobility, including those who are:

- Nonambulatory

- Confined to bed, chairs, wheelchairs, recliners, or couches for long periods of time

- Paralyzed and/or have contractures

- Wearing orthopedic devices that limit function and range of motion

- Dependent on assistance to ambulate or reposition themselves

(WOCN, 2022a)

COMMON QUESTIONS ABOUT PRESSURE INJURIES

Q: Can patients who are conscious and alert still develop pressure injury?

A: Yes. The primary cause for the development of pressure injury is immobility. Patients who are alert and conscious but are fully or partially immobile are at risk for pressure injury development.

ASSESSMENT FOR FRICTION VS. SHEARING

Friction is the rubbing of one surface against another. Patients who cannot lift themselves during repositioning and transferring are at high risk for friction injuries. Friction may contribute to the development or worsening of a pressure injury due to the shear it creates. There are two types of friction:

- Static friction is the force that resists motion when there is no sliding; for example, static friction prevents an individual from sliding down in bed when the head of the bed is elevated.

- Dynamic friction is the force between two surfaces when there is sliding, for example, when a person is sliding down in bed. Skin trauma can result.

Shear is the mechanical force that is parallel to the skin; it can damage deep tissues such as muscle. Shear can result when friction stretches the top layers of skin as it slides against a surface or deeper layers when tissues attached to the bone are pulled in one direction while the surface tissues remain stationary.

Shearing most commonly occurs when the head of the bed is elevated above 30 degrees and the patient slides downward. Friction is most common when patients are turned or pulled up in bed (WOCN, 2022a; EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

ASSESSMENT FOR INCONTINENCE

Moisture from incontinence can contribute to pressure injury development by macerating the skin and increasing friction injuries. Fecal incontinence is an even greater risk for pressure injury development than urinary incontinence because the stool contains bacteria and enzymes that are caustic to the skin. When both urinary and fecal incontinence occur, the fecal enzymes convert the urea in the urine to ammonia, which raises the skin’s pH. When the skin pH is elevated (alkaline), the skin is more susceptible to damage. Pressure injuries are four times more likely to develop in patients who are incontinent than in those who are continent (WOCN, 2022a).

COMMON QUESTIONS ABOUT PRESSURE INJURIES

Q: Are in-dwelling urinary catheters used to prevent pressure injury?

A: Indwelling urinary catheters are not recommended as a means of preventing pressure injury due to the risks associated with their long-term use, such as infection. Short-term use of an indwelling catheter may be recommended when healing an existing pressure injury, but this is done on an individual basis and after thorough wound assessment and consideration of other options.

ASSESSMENT FOR NUTRITIONAL STATUS

Although individual nutrients and their specific roles in preventing pressure injury have not been determined, malnutrition is associated with overall morbidity and mortality. A nutritional assessment is conducted upon admission or when there is a change in the patient’s condition that would increase the risk of malnutrition, such as:

- Patient’s refusal to eat or eating less than usual

- Prolonged NPO status

- Development of a wound or other conditions that increase metabolic demand

- When a pressure injury is not progressing toward healing

The clinician must also keep in mind that patients who are overweight or with obesity can be malnourished and should undergo a nutritional assessment.

Parameters to assess include:

- Current and usual weight

- History of unintentional weight loss or gain

- Food intake

- Dental health

- Ability to swallow and/or feed oneself

- Medical interventions (such as surgeries of the gastrointestinal tract that may affect absorption of nutrients such as vitamin B12)

- Psychosocial factors (such as the ability to obtain and pay for food)

- Cultural influences on food selection

Serum albumin and prealbumin are no longer considered reliable indicators of nutritional status, as there are multiple factors that will decrease albumin levels even with adequate protein intake. These include inflammation, stress, surgery, hydration, insulin, and renal function. Therefore, laboratory evaluation is only one part of a nutrition assessment (WOCN, 2022a; Baranoski & Ayello, 2020).

ASSESSMENT FOR PREVIOUSLY HEALED PRESSURE INJURIES

During patient assessment, the clinician notes the presence of scar tissue or evidence of wound healing over bony prominences, such as the sacral area, and if possible, determines if this is a healed pressure injury. The existence of a previously healed pressure injury places a patient at greater risk for pressure injury recurrence. As a pressure injury heals, it decreases in depth, but the body does not replace the lost bone, muscle, subcutaneous fat, or dermis. Instead, the full-thickness injury is filled with granulation or scar tissue and then covered with new epithelium (EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

Various studies have indicated that patient populations most at risk for pressure injury reoccurrence include those with spinal cord injury and patients with surgical reconstruction, such as flap-closure. Diabetes mellitus and scoliosis were also found to be risk factors for pressure injury reoccurrence (Tsai, 2023).

CASE

Mr. Frank is a 90-year-old man who has been admitted to the hospital with pneumonia. He fell at home three months ago and was also hospitalized at that time. His equally elderly wife denies that she is having any difficulty caring for him and says that he eats well and takes all his medications.

The admitting nurse finds Mr. Frank to be very thin and that he weighs 10 pounds less than when he was hospitalized after his fall. His incontinence brief is saturated with urine, and his perineal skin is raw. He does not move himself in the bed. The nurse recognizes that Mr. Frank is at high risk for developing a pressure injury due to his poor nutrition, his immobility, and his incontinence. The nurse discusses with the physician the patient’s need for a dietitian referral, a pressure reduction mattress, and a barrier product to protect his skin. She alerts the discharge planner that Mr. Frank may also require home health, with personal care services daily if that is available with his insurance coverage.

The physician also requests physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) evaluations and recommendations to improve the patient’s mobility and address self-care needs in order to reduce Mr. Frank’s risk for developing a pressure injury. Prior to discharge, a physical therapist and occupational therapist evaluate and work directly with Mr. Frank on various aspects of mobility and activities of daily living (ADL) performance. They also provide pertinent education and hands-on training for Mrs. Frank in order to optimize her ability to safely care for her husband at home.

For instance, the physical therapist begins to teach Mrs. Frank how to safely assist her husband with bed mobility, transfers to/from a bedside chair and/or commode, and ambulating household distances with an appropriate walker. The occupational therapist teaches Mrs. Frank how to safely assist her husband with ADLs (such as dressing, bathing, and toileting). Both therapists recommend continued PT and OT services in the home setting in order to progress the patient’s functional mobility and independence with ADLs.

If Mr. Frank and his wife continue to have difficulty with his care at home, additional home-based help or an alternate level of care placement may eventually need to be considered.

Risk Assessment Tools and Scales

Several risk assessment tools or scales are available to help predict the risk of a pressure injury, based primarily on those assessments mentioned above. These tools consist of several categories, with scores that when added together determine a total risk score.

The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk is the most validated and widely used pressure injury risk assessment tool in the United States. It was first published in 1987 and has thus been in use for decades across a variety of settings. Two other common scales are the Norton Scale and the Waterloo Scale (Baranoski & Ayello, 2020; WOCN, 2022a).

The Cubbin-Jackson Scale was created specifically to determine pressure injury risk in critically ill patients. In one study, it was found to have comparable prognostic validity to the Braden Scale, and in a second study, its prognostic validity was found to surpass the Braden Scale when used in a group of critically ill trauma patients (Higgins, 2020).

The clinician uses these tools to help determine risk so that interventions can be started promptly. These tools are only used for assessing adults, although the Braden-Q Scale has subcategories that relate to assessing children.

It is important that when the clinician uses a scale, the scale must not be altered in any way, meaning there cannot be shortcuts or changes to the definitions. Any changes would alter the accuracy and usefulness of the scale in predicting the risk of developing pressure injuries. The same scale should be used consistently throughout the facility, and if this is not a standard practice, it is one that clinicians should advocate for.

Assessment tools notwithstanding, if a patient has other major risk factors present (such as age, fever, poor perfusion, etc.), the patient may be at higher risk than a risk score would indicate. Clinicians must work to assure that, regardless of the specific risk assessment tool being used, the professionals using it are proficient in its use and knowledgeable regarding potential risk factors within their patient population that are not accounted for in the assessment tool they are using (WOCN, 2022a).

BRADEN SCALE

The Braden Scale consists of six categories:

- Sensory perception: Can the patient respond to pressure-related discomfort?

- Moisture: What is the patient’s degree of exposure to incontinence, sweat, and drainage?

- Activity: What is the patient’s degree of physical activity?

- Mobility: Is the patient able to change and control body position?

- Nutrition: How much does the patient eat?

- Friction/shear: How much sliding/dragging does the patient undergo?

There are four subcategories in each of the first five categories and three subcategories in the last category. The scores in each of the subcategories are added together to calculate a total score, which ranges from 6 to 23. The higher the patient’s score, the lower their risk.

- Less than mild risk: ≥19

- Mild risk: 15–18

- Moderate risk: 13–14

- High risk: 10–12

- Very high risk: ≤9

It is recommended that if other risk factors are present (such as age, fever, poor protein intake, hemodynamic instability), the risk level be advanced to the next level. Each deficit that is found when using the tool should be individually addressed, even if the total score is above 18. The best care occurs when the scale is used in conjunction with nursing judgment. Some patients will have high scores and still have risk factors that must be addressed, whereas others with low scores may be reasonably expected to recover so rapidly that those factors need not be addressed (WOCN, 2022a).

(See also “Resources” at the end of this course.)

NORTON SCALE

The very first pressure injury risk evaluation scale, called the Norton Scale, was created in 1962 and is still in use today in some facilities. It consists of five categories:

- Physical condition

- Mental condition

- Activity

- Mobility

- Incontinence

Each category is rated from 1 to 4, with a possible total score ranging from 5 to 20. A score of less than 14 indicates a high risk of pressure injury development.

WATERLOO SCALE

The Waterloo Scale, mainly used in Europe, was developed in 1987. This scale consists of seven items:

- Weight for height

- Skin type

- Sex and age

- Malnutrition screening

- Continence

- Mobility

- Special risk factors

Potential scores range from 1 to 64. The tool identifies three categories of risk: at risk (score of 10–14), high risk (score of 15–19), and very high risk (score of 20 and above).

CUBBIN-JACKSON SCALE

The Cubbin-Jackson Scale consists of ten items:

- Patient age

- Patient weight

- Skin condition of the entire body

- Mental status

- Mobility

- Nutrition

- Respiratory status

- Incontinence

- Hygiene

- Hemodynamic status.

It utilizes a four-point scale, with scores ranging from 10 to 40. The lower the score, the higher the risk for pressure injury (Choi, 2013).

THERMAL IMAGING

Research has shown that changes in temperature frequently occur before there are changes in skin color. Thermal imaging has therefore become an established tool in the assessment of deep tissue pressure injury (DTPI). Human skin produces infrared radiation, which allows long-wave infrared thermography (thermal imaging) to detect changes in skin temperature. It has been found that alterations in skin color related to unrelieved pressure more often develop into a pressure injury when the temperature of the area at baseline is below that of the adjacent skin.

In a study of 114 patients in an ICU, thermal imaging was used along with clinical assessment to evaluate anatomical sites at high risk for DTPIs, namely, the coccyx, sacrum, and bilateral heels. Thermal assessments were performed using the Scout Device, which is FDA approved for this procedure. Detecting early changes in skin temperature before there were any visible signs of DTPI allowed for proactive interventions, and data from the study demonstrated about a 60% reduction in the number of DTPIs compared to the unit’s usual rate.

Study authors pointed out that thermal imaging can result in significant cost savings, reduced expenditure in treating pressure injury, and reduced settlements related to legal liability for hospital-acquired pressure injury. Clinicians require training in the correct use of thermal injury equipment (Koerner, 2019).

Another study demonstrated that infrared thermography has the ability to identify tissue damage one day before visual discovery of a pressure injury. It was found that the infrared thermography model used in the study could perform an objective evaluation of subcutaneous tissue abnormalities. Early-stage detection allows for rapid implementation of preventive measures (Jiang, 2022).