PAIN ASSESSMENT

A precise and systematic assessment of pain is important for making an accurate diagnosis and for the development of an effective treatment plan. Pain is a multidimensional phenomenon that produces strong emotional reactions that can affect an individual’s function, quality of life, emotional state, social and vocational status, and general well-being. Therefore, it is recommended that pain be assessed using a multidimensional approach and that these various impacts be addressed and included in the diagnostic formulation.

A comprehensive pain assessment includes a history of the pain, behavioral observations, past medical history, medications, family history, a physical examination, and if necessary, diagnostic testing.

Pain History

A pain assessment begins with the history of the problem and can be obtained from written documents and from interviews with the person in pain as well as family members and other caregivers. Pain is a subjective symptom, and pain assessment is, therefore, based on the patient’s own perception of pain and its severity.

ELEMENTS OF PAIN HISTORY

Because pain is subjective, a self-report is considered the “gold standard,” or the best, most accurate measure of a person’s pain. One method to obtain a complete pain history is the PQRST assessment (see box).

PQRST PAIN ASSESSMENT

Provocation/Palliation (P)

- What were you doing when the pain started?

- What caused the pain?

- What seems to trigger it (e.g., stress, position, certain activities)?

- What relieves it (e.g., medications, massage, heat/cold, changing position, being active, resting)?

- What aggravates it (e.g., movement, bending, lying down, walking, standing)?

Quality/Quantity (Q)

- What does the pain feel like (e.g., sharp, dull, stabbing, burning, crushing, throbbing, nauseating, shooting, twisting, stretching)?

Region/Radiation (R)

- Where is the pain located?

- Does the pain radiate, and if so, where?

- Does the pain feel like it travels/moves around?

- Did it start somewhere else and is now localized to another spot?

- Is it accompanied by other signs and symptoms?

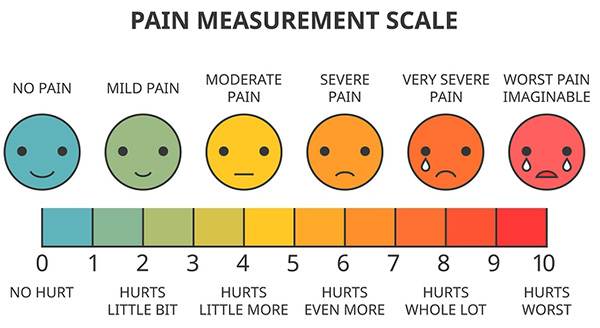

Severity Scale (S)

- How severe is the pain on a scale of 0–10, with 0 as no pain and 10 as the worst pain ever?

- Does the pain interfere with activities?

- How bad is the pain at its worst?

- Does it force you to sit down, lie down, slow down?

- How long does an episode last?

Timing (T)

- When or at what time did the pain begin?

- How long did it last?

- How often does it occur (e.g., hourly, daily, weekly, monthly)?

- Is the pain sudden or gradual in onset?

- When do you usually experience it (e.g., daytime, night, early morning)?

- Are you ever awakened by it?

- Does it ever occur before, during, or after meals?

- Does it occur seasonally?

(Crozer Health, 2022)

ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Pain scores have been accepted as the most accurate and reliable measure for assessing patients’ pain and response to pain treatment. Scales have been developed to estimate and/or express the patient’s pain using two methods: unidimensional and multidimensional measures.

Unidimensional pain scales allow the patient to use either words or images to describe their pain. These scales assess a single dimension of pain, typically pain intensity, through patient self-reporting. These are useful for a patient in acute pain when the etiology is known. Examples of unidimensional scales include:

- Numerical rating scale (NRS)

- Visual analogue scale (VAS)

- Verbal rating scale (VRS)

- Faces scale

(UFHealth, 2022)

Unidimensional visual analogue scale (VAS) measuring pain intensity. (Source: Lukpedclub/Bigstock.com.)

Multidimensional scales are more complex. They measure pain intensity, its nature or quality, its location, and its impact on mood or activity. These scales are useful in complex or persistent acute or chronic pain. Examples include:

- Multidimensional Pain Inventory

- McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)

- Brief Pain Inventory Short Form (BPI-SF)

(UFHealth, 2022)

Behavioral Observations

Most people who are experiencing pain usually show it either by verbal complaint or nonverbal behaviors or indicators. It is important, however, to remember that people in pain may or may not display behaviors that are considered an indication of “being in pain,” and making judgments about their honesty is inappropriate. The following table lists some typical behavioral and physiologic indicators of pain that healthcare providers may observe when completing a pain assessment.

| Type of Indicator | Examples |

|---|---|

| (Toney-Butler, 2019; Victoria Department of Health, 2021) | |

| Facial expressions |

|

| Vocalizations |

|

| Body movements |

|

| Activity/routine changes |

|

| Social interaction |

|

| Protective movements |

|

| Mental status changes |

|

| Physiologic changes |

|

Medical and Surgical History

Relevant past medical and surgical history may help determine the etiology of pain (e.g., diabetes, history of cancer, rheumatic disease) and may reveal conditions that affect the choice of therapy. This includes:

- Prior medical illness (e.g., renal or hepatic insufficiency/disease, which affects choice of analgesic and dosing)

- Prior psychiatric illnesses (e.g., depression or anxiety)

- Prior surgeries, scarring, repeated surgeries (may increase sensitivity to pain)

- Past injuries and accidents

- Coexisting acute or chronic illnesses

- Chemical dependence

- Prior problems with pain and treatment outcomes

- Investigations conducted (e.g., medical imaging)

A complete list of current medications (past and present) and usage, including over-the-counter medications and alternative, herbal, and natural products, is obtained, as well as the patient’s report of their effectiveness. Evaluation of physiologic tolerance (diminished response) related to chronic use of some medications and use of alcohol and illicit drugs is also included.

Family history is important, as it may give a clue to any predisposition to pain-causing illnesses and conditions that may involve the connective tissues (e.g., kyphoscoliosis), metabolism (e.g., sickle cell disease), and neurologic system (e.g., familial amyloid neuropathy). Other types of disorders that may cluster in families include fibromyalgia, persistent back pain, irritable bowel syndrome, and some types of arthritis (CASN/AFPC, 2021).

Review of Systems

The review of systems may suggest conditions that are associated with nociplastic sensory hypersensitivity (pain with no clear evidence as to source), and may support a syndromic pain diagnosis such as chronic fatigue, headache, or widespread conditions such as fibromyalgia (Tauben & Stacey, 2022).

The psychosocial history is an important aspect to a review of systems, because what first appears to be a simple problem can become much more complex due to the influence of psychological and social factors. A psychosocial history includes:

- Psychological history: emotional state, personality, self-esteem

- History of mental illness and past traumatic experiences

- Family systems

- Social history: economic factors, education, social class, culture/ethnicity

(Caring to the End, 2022)

Functional Assessment

Components of a functional assessment include:

- Ability to complete activities of daily living: Hygiene, dressing, cooking, eating, walking, transferring, toileting, shopping, housework, etc.

- Mood/mental health: Presence of depression, anxiety, social isolation, lack of energy and/or interest in social interactions

- Mobility: Ability to move (with or without assistance), including bed mobility, transfers, ambulation, stair climbing, etc.; use of mobility and/or assistive devices (e.g., walker, cane); and ability to engage in activities enjoyed before experiencing pain

- Work ability: Occupation, usual housework, home maintenance

- Sleep: Patterns, interruptions, medication use

- Relations with other people:

- Serving in a caregiving role (e.g., childcare, eldercare)

- Ability to fulfill family obligations

- Ability to engage in social activities and interactions

- Ability to have intimate relationships

- Support needed and available

Physical Examination

A systematic, targeted, pain-focused physical examination is most fruitful when the pain history interview and behavioral observations are conducted at the same time. Because pain may be referred from some other area of the body, the examination should include a full visual scan from head to toe.

- Mental status examination. This includes cognitive function, mood and affect, thought process and content, judgment, and insight. Signs of mental deterioration should match with the patient’s history or should prompt a search for an underlying pathology.

- Vital signs. They can provide objective information about the patient’s general health status, and, if abnormal, may be a relative contraindication to certain interventions. Vital signs may be elevated when a patient is experiencing acute pain. Elevated temperature may signal an infectious cause for pain.

- General inspection. This begins when the clinician first encounters the patient and notes any obvious sign of pain, such as limping, unusual posture of the body, splinting or guarding, facial expression, vocalizations, and the presence of obesity. The examiner looks at skin color and pigment changes, which may indicate inflammation, sympathetic dysfunction, or a prior herpes zoster eruption. Atrophy may indicate guarding and lack of use or denervation. Poor healing indicates poor perfusion possibly associated with ischemic injuries, diabetic neuropathy, or sympathetic dysfunction. Surgical scars should be identified, particularly in the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spinal areas.

- Auscultation of the lungs, heart, and bowel sounds. This should be done as part of a routine examination, and especially if pertinent to the complaint.

- Palpation. Touch is used to gather information such as skin temperature, pulses, internal masses, tenderness, or rigidity. The painful area is demarcated, with the clinician feeling for changes in pain intensity within the area, trigger points, and changes in sensory or pain processing. Widespread pain hypersensitivity to palpation may suggest a more complex centralized pain process.

- Musculoskeletal examination. This includes both inspection and palpation for abnormal movements, range of motion, functional limitations, swelling and tenderness of the joints, temperature and color changes, crepitation, and deformity. Inspection of the affected area is done, noting signs of recent trauma as well as evidence of more remote trauma such as scarring. It is important to determine secondary pain, even in patients whose primary source of pain is musculoskeletal. For example, if there is a knee problem, structures that directly affect the function of the knee (such as the low back, hip, foot, ankle, and supporting structures of the knee) are evaluated.

- Neurologic examination. This includes evaluating level of alertness, degree of orientation, behavior and mood, intellectual function, motor system (muscle tone and strength), and balance. A comprehensive sensory examination includes tests for light touch, pinprick, pressure, vibration, joint position, and heat and cold sensation. The examination also involves observation of the individual’s gait, coordination, and balance and testing for abnormal deep tendon reflexes. Hyperreflexia may be indicative of a number of possible conditions and indicate spinal cord myelopathy (e.g., compression, syrinx, or multiple sclerosis).

- Abdominal, pelvic, or rectal examination. This assesses for suspected disease conditions that can cause pain referred to the back, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, or prostatitis.

(Anesthesia Key, 2019; Tauben & Stacey, 2022)

Diagnostic Testing

Although there are no diagnostic tests available as yet to determine how much pain a person is experiencing, and no test that can measure the intensity or location of pain, there are a number of tests that can be done to determine the cause or source of pain.

LABORATORY TESTS

Routine blood studies are not indicated, but directed testing should be ordered when specific causes of pain are suggested by the patient’s history or physical examination.

- Complete blood count (CBC), to detect the presence of an infection and some kinds of cancer

- Comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), to give a picture of a person’s general health and to consider drug clearance and metabolism in the setting of renal or liver dysfunction that may affect treatment options

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), to assess for inflammation and autoimmune disorders

- C-reactive protein (CRP), to assess for infection, inflammation, and possible elevation due to polymyalgia rheumatica or rheumatoid arthritis

- Vitamin B12, B6, and folate levels, to assess for deficiencies that cause neurologic symptoms

- Fasting blood sugar (FBS) and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), to test for diabetes or to monitor control of diabetes

- Hemoglobin S (HbS or Hgb), to test for sickle cell disease

- HIV antibodies (ELISA or Western Blot), to detect HIV infection

- HSV antibodies, to assess for herpes simplex virus infection

- Lyme antibody testing, to rule out Lyme’s disease, which can progress to the joints and peripheral nerves

- Rheumatologic tests (rheumatoid factor, ESR, ANA), to rule out rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus) and infections (e.g., hepatitis, syphilis)

- HLA-B27 antigen, a genetic marker, to rule out ankylosing spondylitis and reactive arthritis

(Nnanna, 2021; Asher, 2022)

IMAGING AND ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC TESTING

- Plain X-ray films, to demonstrate bony pathology and some soft tissue tumors

- Ultrasound, to help diagnose strains, sprains, tears, and other soft tissue conditions

- Myelograms using a contrast injected intrathecally, to assess the spinal cord, subarachnoid space, or other structures for changes or abnormalities

- Computerized tomography (CT), to obtain images that give details of anatomic structures

- Discogram, to view and assess internal structure of a disc to determine if it is the source of pain

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for superior soft tissue visualization, to diagnose spinal disc disease or neural compression; best for evaluation of spinal alignment and investigation for infections or tumors

- 18-FDG PET and MRI, a newer PET/MRI method, to pinpoint regions responsible for causing pain

- Functional MRI, to provide data on metabolic and functional measurements in addition to anatomic details

- Bone scans, to help diagnose tumors of the bone or metastatic disease, osteomyelitis, fractures, joint disease, avascular necrosis, and Paget’s disease

- Electromyography (EMG), to detect abnormal electrical activity in many diseases and conditions

- Nerve conduction studies (NCS), to measure changes in the peripheral sensory and motor nerves by stimulating them in various places along their courses and to isolate a specific site of injury

- Diagnostic nerve block, which numbs pain in specific nerve locations, thereby allowing the patient’s response to the nerve block, to help determine the cause and site of pain

- Somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP), to assess for generalized disorders of the nervous system (e.g., multiple sclerosis)

- Electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG), to identify neural pathways signaling chronic pain

(Agranoff, 2020; Wheeler, 2021; O’Connor, 2020)

Psychological Examination

A psychological assessment is intended to identify emotional reactions, maladaptive thinking and behavior, and social problems that can contribute to pain and disability. A psychological assessment includes a semistructured clinical interview and self-report instrument to assess differences in the domains of pain experience, functional impairment, and pain-related disability.

There are three main purposes for psychological and psychiatric evaluations related to assessment of pain. These are to:

- Assess the impact of personality, psychiatric, physical, and motivational factors that can affect symptoms of chronic pain

- Measure psychiatric and psychological distress stemming from pain due to an incident or an injury at work

- Determine eligibility for spinal cord stimulator or morphine pump placement

(Comprehensive MedPsych Systems, 2021; Jamison & Craig, 2022)

PAIN AND RISK FOR SUICIDE

Chronic pain is prevalent in people who die by suicide. Chronic, nonmalignant pain, independent of other factors such as sociodemographic and physical and mental health status, doubles the risk of suicide. Risk factors for suicidal ideation and behavior in those with chronic pain include:

- Multiple pain conditions

- Severe pain

- More frequent episodes of intermittent pain (e.g., migraines)

- Longer duration of pain

- Sleep onset insomnia

Psychological processes relevant to patients with chronic pain who may be at risk for suicide include helplessness and hopelessness, a desire to escape the pain, and problem-solving deficit. Evaluation should include patient and family past histories of suicidal ideation and behavior (Schreiber & Culpepper, 2022).

Barriers to Assessing Pain

Optimal comprehensive pain assessment requires removal of barriers in the healthcare system; among healthcare professionals; and in patients, family, and society.

Healthcare professional barriers: Studies have found that nurses rely on physiologic parameters or observed behaviors rather than using formal pain assessment tools. Deficits in knowledge related to pain assessment and management were found most frequently to be related to:

- Behavioral pain indicators

- Perceptions of a patient’s pain tolerance

- Use of verbal and nonverbal pain assessment tools

- Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain management

Although self-reporting is the gold standard for pain assessment, nurses have been found to perceive self-reporting of pain as an inaccurate measure of intensity and tend to encourage patients to endure pain as long as they can before offering analgesia (Rababa et al., 2021).

Another barrier is healthcare provider bias, which may manifest as prejudice against a particular group or the use of stereotypes to categorize a particular patient as not having pain or a particular illness as not causing pain. For instance, research has shown that Black Americans are systematically undertreated for pain relative to White Americans and that this is related to false beliefs such as “Black people’s skin is thicker than White people’s skin” (Hoffman et al., 2016).

Patient and family/caregiver related barriers: The most frequently reported barrier is the patient’s inability to communicate (see also “Assessing Pain in Special Populations” below). Also, the biopsychosocial nature of pain means that a person’s knowledge and personal beliefs about pain and its treatment may greatly influence how well their pain can be managed. A patient history of substance abuse, alcoholism, or suicide attempt may impede pain management as well.

System-related barriers include a lack of standardized assessment forms and tools for critically ill and nonverbal patients, lack of standardized guidelines and protocols for pain evaluation and control, heavy workloads of nurses, and nursing staff shortages (Rababa et al., 2021; Lee, 2022).

Assessing Pain in Special Populations

Accurate pain assessment can be challenging in certain populations, including infants, children, and cognitively impaired individuals, due to communication barriers. Because pain is a subjective experience, being unable to obtain this subjective information can lead to a less-than-optimal assessment.

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN IN NEONATES

Since the 1980s, evidence has shown that preterm and term infants experience pain and stress in response to noxious stimuli. As general rule, anything that causes pain in adults or older children will also cause pain in neonates. Effective neonatal pain assessment is essential for optimal pain management and requires appropriately sensitive and accurate clinical pain assessment tools as well as clinical staff that is trained to detect neonatal pain using such tools.

Neonatal pain assessment tools rely on surrogate measure of physiologic and behavioral response to pain or noxious stimuli. Examples of scales most commonly used for acute pain assessment include:

- PIP-R (Premature Infant Pain Profile-Revised)

- N-PASS (Neonatal Pain Agitation and Sedation Scale)

- NIPS (Neonatal Infant Pain Scale)

- CRIES (crying, requires oxygen, increased vital signs, expression, sleepless)

- NFCS (Neonatal Facial Coding System)

- BIPP (Behavioral Infant Pain Profile)

There are challenges, however, that limit the accuracy of using such tools, as they require evaluation by observers among whom there may be significant variability. These tools also require observation, mental calculation, and recording of 3 to 10 parameters in real time, all while the provider is performing a painful procedure. At this time there is no “gold standard” established for assessment of pain in the neonate (Anand, 2022).

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN IN INFANTS AND CHILDREN

Assessment of pain severity in children is performed by self-report or by behavioral observational scales in those unable to self-report. Self-reporting relies on the cognitive ability to understand that pain severity can be measured along a continuum. Younger children (ages 3 to 8 years) are capable of quantifying pain and translating it to a visual representation. Visual analogue pain scales based on a series of faces showing an increase in distress or pain are used for this age group. The reliability of pain assessment increases with age and cognitive ability of the child.

Assessment of pain in older children (ages 8 to 11 years) is generally performed utilizing visual analogue tools that rate the intensity of pain on a horizontal or numeric scale. Adolescents can also rate pain using a numerical scale, and a description of pain can usually be obtained from pain history.

The following pain-location tools can be used to determine location of pain in both children and adolescents. These tools use a graphic outline of the body, and the patient is asked to color in the area of the body where pain is being experienced:

- Adolescent and Pediatric Pain Tool

- Pediatric Pain Questionnaire

The following observational tools are used for assessing pain in infants and children who are unable to self-report. They are based on facial expressions, ability to be consoled, level of interactions, limb and trunk motor responses, and verbal responses:

- rFLACC (Revised Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) for nonverbal children

- NCCPC-PV (Non-Communicating Children Pain Checklist–Postoperative Version) for nonverbal children

- NAPI (Nursing Assessment of Pain Intensity) for newborn to 16 years of age

- PPP (Pediatric Pain Profile) for nonverbal children

- INRS (Individualized Numeric Rating Scale)

Pain can also be assessed by identifying the impact it has on daily life, including participation in school activities, sports, and relationships (Hauer & Jones, 2021).

Extremely immature and chronically ill infants and children who have been exposed to repeated painful experiences have difficulty generating a pain response. Caution should be taken not to interpret this response as an indication that the patient is not in pain. Also, chronic pain can sap energy, causing an infant or child to be withdrawn and become still and quiet (Martin et al., 2019).

In children ages 3 to 4 years, self-report measures may be used. However, children may underreport their pain to avoid future injections or other procedures aimed at alleviating pain (Kishner, 2018).

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN IN THE COGNITIVELY IMPAIRED

Many conditions can lead to cognitive impairment that can make pain assessment difficult, such as head trauma, memory deficits, unconsciousness, and delirium. Dementias are the leading cause of impaired cognition in older adults. These individuals may have communication barriers and challenges when complex pain assessment tools are used. In these instances, behavioral observation–based assessments are optimal. Behaviors include:

- Facial expressions (e.g., frowning, grimacing, rapid blinking)

- Verbalizations/vocalizations (e.g., moaning, sighing, verbal abuse)

- Body movements (e.g., rigid, tense, guarding, fidgeting, inactive, pacing)

- Altered interpersonal interactions (e.g., aggression, resistance to care, disruption, withdrawal)

- Activity patterns (e.g., changes in appetite or sleep, cessation of regular routines)

- Mental status changes (e.g., increased confusion, irritability)

There are various pain rating scales available, with none yet shown to be clearly superior. Clinicians, therefore, should choose one tool and use it consistently to ensure uniformity among healthcare providers across shifts. Examples include:

- Doloplus-2

- Assessment of Discomfort in Dementia Protocol (ADDP)

- Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD)

- Checklist of Nonverbal Pain Indicators

- Pain Assessment for the Demented Elderly

- Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC)

- Abbey pain scale

(Wilner & Arnold, 2022)

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN IN THE OLDER ADULT

Pain is prevalent in older persons, and this increases with age, but pain in the absence of disease is not a normal part of aging. Pain is of significant intensity in about one fifth of older adults, and pain is the most common reason for an older person to consult a physician.

Issues that can make assessment of pain in this population difficult include comorbidities, polypharmacy, and cognitive dysfunction. Older adults may believe that their pain is a normal part of aging or that it cannot be treated, or they may not report it. They may also be concerned that treatment will lead to expensive tests and/or increased medications.

Multiple accompanying medical comorbidities can make it difficult to distinguish acute pain caused by a new illness from that of an existing condition. It is important to learn what the patient’s baseline level of functioning is, and obtaining a focused history will help determine this.

Communication may be impaired as a result of decreased hearing and vision, which may limit verbal communication as well as the use of written pain assessment tools. Recognizing that some patients require extra time to consider a posed question and formulate an answer and speaking more slowly or distinctly are important considerations.

Family members, advocates, or caregivers can provide information about the patient’s baseline cognitive and physical functioning and can validate history. They may also provide some of the best evidence for heightened or chronic pain, which can include increased agitation; changes in functional status, body posture, or gait; and social isolation.

The best pain assessment is obtained by using a standardized tool validated for use in the older adult. It should be sensitive to cognitive, language, and sensory impairments. Commonly used assessment tools for this age group include:

- Visual analogue scales

- Numeric rating scales

- McGill Pain Questionnaire

- Pain Attitudes and Beliefs Scale

- Brief Pain Inventory

- Geriatric Pain Measure

(Buowari, 2021)