TREATMENT OF BREAST CANCER

For many years, breast cancer was assumed to be a localized disease, and the treatment of choice was also localized: a radical mastectomy. However, when it was shown that these often disfiguring and debilitating surgeries were not improving survival or decreasing recurrence rates, this practice was abandoned.

As technology gets ever more sophisticated at detecting cancer cells, the view of breast cancer as a systemic disease gains more support. Thus, treatment of breast cancer today generally includes some combination of localized (surgery and radiation therapy) and systemic treatments (chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, targeted biological therapies, or immunotherapy).

Surgery is often the primary treatment for breast cancer, followed by radiation therapy. Depending on a number of factors, chemotherapy and/or hormone therapy may also be administered over weeks or months. The medical oncologist may recommend one or more of these therapies, depending on the patient’s age and the stage and other characteristics of the tumor. The goal of systemic treatment is to destroy any cancer cells that have moved beyond the breast to other areas of the body and to achieve long-term remission of the cancer.

Medical scientists previously thought that a tumor had to reach a certain size before cancer cells moved into the bloodstream and traveled to other parts of the body. However, research has shown that cancer cells can migrate out of the breast very early in the development of a tumor. This is why systemic therapies (chemotherapy, biological therapy, immunotherapy, and/or hormone therapy) are recommended for premenopausal women with breast cancer even if there is no evidence of cancer in the lymph nodes.

Radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted biological therapy are referred to as adjuvant therapy, or therapies given after surgical intervention. However, there are situations when the sequencing of surgery and the administration of systemic therapies may need to be modified.

Some practitioners prefer to administer chemotherapy and/or hormone therapy before surgery to remove the tumor, which is called neoadjuvant therapy. Neoadjuvant therapy may shrink large tumors, thereby enabling patients to have a lumpectomy rather than a mastectomy. It also enables the oncologist to evaluate a drug’s effectiveness in an individual patient.

Timing of neoadjuvant therapy also has implications for lymph node assessment (see below). Current practice is to perform sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) before systemic therapies (ACS, 2021d). If no cancer cells are found in the sentinel node(s), the patient can avoid axillary lymph node dissection and avoid radiation to the axilla. This can reduce the risk of lymphedema, a painful, disfiguring, chronic swelling that can affect the entire arm and hand.

Surgical Interventions

Surgery is a cornerstone of treatment for breast cancer. Whether it precedes or follows systemic therapy, however, depends on a number of factors, including the stage of the cancer, the age of the patient, and the preferences of the treatment team. Patients with breast cancer may have a lumpectomy or one of three types of mastectomy (surgery to remove the breast).

Depending on the patient’s age, general health, and the size, type, and stage of the tumor, they may need only surgery and perhaps radiation therapy. But many patients, especially those who have not reached menopause, may need to consider adjuvant systemic therapy: chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or targeted biological therapy (NCCN, 2022a).

LUMPECTOMY

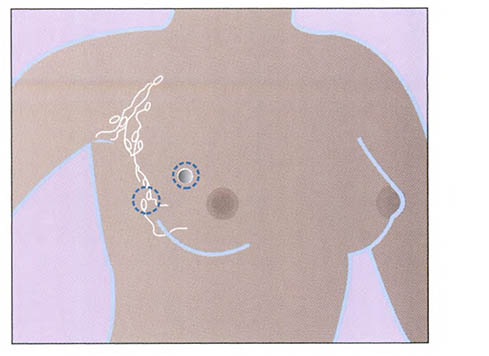

Also called segmental mastectomy or wide local excision (WLE), lumpectomy is the removal of the tumor and a narrow margin of the surrounding tissue. The margin is taken to increase the chance that all of the cancer cells are removed. This type of surgery allows as much of the breast tissue as possible to remain. Because tumors are now detected at an earlier stage and often are smaller in size, lumpectomy is a common procedure.

Lumpectomy may not produce a good cosmetic result for a patient who has a large tumor in a small breast. However, large tumors sometimes can be reduced prior to surgery either by neoadjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or biologic therapy (e.g., HER2-directed), making lumpectomy a viable option. These neoadjuvant therapies also show whether the tumor is responding to a specific therapy.

Current options for treatment include lumpectomy followed by a course of radiation therapy to destroy any remaining cancer cells that could cause recurrence or metastasis. Additional options may include accelerated (hypofractionated) partial breast irradiation and proton beam radiation (see also below under “Types of Radiation”). Radiation therapy reduces the locoregional recurrence rate and risk of breast cancer death.

Some patients, particularly older patients with very small, slow-growing tumors (<1 cm), may choose not to have radiation therapy (NCCN, 2022a).

Lumpectomy. (Source: National Institutes of Health.)

MASTECTOMY

Mastectomy is a general term for removal of the breast. A mastectomy may be performed when a lumpectomy is not possible or based on the preference of the patient. There are three types of mastectomy: simple, modified radical, and radical.

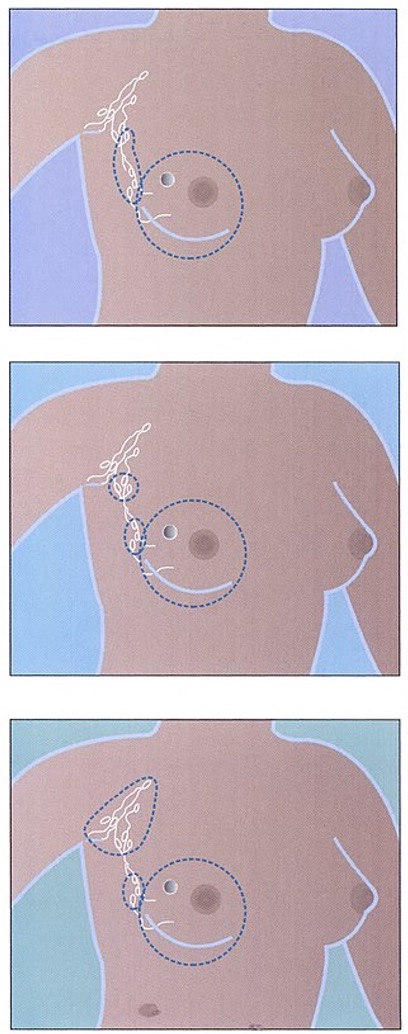

- A simple mastectomy involves the removal of the breast tissue, skin, areola, and nipple, but not the lymph nodes. This procedure is generally used when axillary lymph nodes do not need to be removed, as evidenced by a negative sentinel node examination.

- A modified radical mastectomy involves the removal of the entire breast, including the skin, areola, and nipple, along with the axillary lymph nodes, but leaves the chest wall muscles intact.

- A radical mastectomy involves removal of the entire affected breast, the underlying chest muscles, the lymph nodes under the arm (axillary node dissection), along with some additional fat and skin. Radical mastectomies are rarely used today. This type of mastectomy is generally limited to cases when cancer has spread to the chest wall muscles.

Some patients with cancer in one breast may choose to have the other breast removed at the time of their mastectomy. This is called a bilateral mastectomy, and removal of the other breast is considered a prophylactic (preventive) measure. Prophylactic mastectomy reduces the risk of breast cancer developing in the contralateral breast, but it is not an absolute guarantee because of the systemic nature of the disease.

Total (or simple) mastectomy (top), modified radical mastectomy (middle), and radical mastectomy (bottom). (Source: National Institutes of Health.)

PHYSICAL THERAPY AND BREAST CANCER SURGERY

A physical therapist may work with a breast cancer patient before surgery as part of a prehabilitation plan. Prehabilitation is the period of time after diagnosis and before treatment starts. Many patients have a few weeks during this time to start assessments and learn the important steps to take to prevent complications such as lymphedema.

The goals of physical therapy during prehabilitation are:

- Take baseline measurements, such as the circumference of both arms and range of motion (ROM) of shoulder movements

- Identify any individual concerns that may affect recovery, such as muscle weakness, deconditioning, and pain syndromes

- Educate the patient and family on lymphedema and how to prevent complications

- Establish a personalized exercise program for before and after surgery

After surgery, the goals of physical therapy are to minimize side effects of treatment and improve function. This may include:

- Manual therapy: Hands-on treatment to the joints, muscles, and incision areas aimed at reducing range of motion problems, cording, scar formation, and pain and swelling

- Lymphedema treatment: Assisting with manual lymphatic drainage, compression bandaging, assessment for garments, and exercise instruction

- Exercise plan: Continued support with an individualized exercise plan during and after treatment (and into the survivorship period) to reduce side effects such as fatigue, pain, and lymphedema

(Koesters, 2021)

LYMPH NODE ASSESSMENT AND REMOVAL

Lymph nodes are part of the immune system and linked by tiny vessels within the entire lymphatic system. Lymph nodes and the lymph vessels drain the excess fluid that is not absorbed by blood vessels. Lymph nodes filter out foreign substances such as bacteria and cancer cells as part of the body’s immune system.

In addition to performing breast surgery, surgeons examine underarm lymph nodes for cancer cells using either an axillary lymph node dissection or sentinel lymph node biopsy. Lymph node assessment is performed for two reasons: 1) to determine whether the cancer has spread beyond the breast, and 2) to remove any cancerous nodes. Oncologists use this information in staging the tumor and as a basis for planning optimal treatment (ACS, 2021d).

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) involves removal of a large number of axillary lymph nodes for examination by a pathologist. Formerly a part of all breast cancer surgeries, axillary dissection has been replaced in many cases by a newer procedure called sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is also called sentinel lymph node dissection. This newer procedure offers a less-traumatic alternative for determining whether the cancer has spread beyond the breast. The SLNB procedure focuses on locating the specific lymph nodes (sentinel nodes) that are first to receive drainage from the breast tumor.

SLNB is most appropriate for patients with early-stage breast cancer with clinically negative axillary nodes. For patients who have axillary nodes identified positive for cancer cells with the SLNB, ALND completion is performed. Physical examination, imaging studies, and tumor size help determine the most appropriate type of lymph node sampling.

SLNB results in fewer complications and less lymphedema than ALND. The procedure is usually done at the same time as either lumpectomy or mastectomy. Before the tumor is removed, a radioactive substance is injected into the area surrounding the tumor. About an hour later, in the operating room, the surgeon injects a special dye near the tumor and makes a small incision in the underarm area. By tracking the path of the dye and the radioactive substance, the surgeon can identify and remove the sentinel node (or up to three nodes) where cancer cells from a breast tumor would reach first.

The node(s) are sent to the pathology laboratory for examination while the patient is still in surgery. If no cancer cells are found in the sentinel node(s), no further nodes are removed—only the tumor itself. If cancer cells are found, however, the remaining nodes are removed and analyzed using standard axillary dissection technique (NCI, 2022).

LYMPHEDEMA AS A SIDE EFFECT OF SURGERY

Lymphedema is the interstitial collection of protein-rich fluid due to disruption of lymphatic flow. It is a common complication of axillary node dissection and radiation therapy. Breast cancer treatment is the leading cause of secondary lymphedema.

When the patient has an axillary surgery or a SLNB and radiation, the risk of lymphedema increases. Most patients who develop lymphedema will do so within three years of surgery, but it is important that patients understand it remains a lifetime risk.

Signs and symptoms of lymphedema include:

- Fullness, aching, pain, or heaviness in the arm

- Feeling of tightness of the skin of the arm and hands

- Reduced range of motion of the affected arm

- Clothing or rings that no longer fit on the affected side

(Manahan, 2022)

Diagnosis and evaluation of lymphedema is done with imaging of the lymphatic system called lymphoscintigraphy (radionuclide imaging). This type of imaging may be performed on patients at high risk for lymphedema. MRI imaging may also be added to gain additional information about the extent of lymphedema and nodal involvement.

The risk and extent of developing lymphedema depend on whether and how many lymph nodes are removed and whether or not radiation treatment is added to surgery.

It is critical to recognize lymphedema at the earliest possible stage to educate the patient and initiate treatment to prevent worsening of the condition. The table below describes the stages of lymphedema based on severity.

| Stage | Type |

|---|---|

| (ACS, 2021h) | |

| 0 | No swelling, but subtle symptoms such as feeling the affected area is heavy or full or that the skin is tight |

| 1 | Swelling of the affected area, increased size or stiffness of the arm; swelling that improves when the affected arm is raised |

| 2 | More swelling than stage 1, which does not improve when the arm is elevated; arm hard and larger than in stage 1 |

| 3 | Much more swelling than stage 2, possibly so severe that the patient cannot lift or move the arm on their own without using their other arm; dry and thick skin; fluid leaking from the skin or blisters forming |

Risk of lymphedema is lifelong after breast cancer surgery or radiation therapy, especially when axillary lymph nodes are involved. Therefore, patients must reduce risks of developing the disorder through precautionary measures such as:

- Controlling one’s weight

- Avoiding arm constriction (no restrictive clothing or blood pressure cuffs on the affected side)

- Avoiding punctures (no injections, IVs, blood draws, or acupuncture on the affected side)

- Using compression garments as appropriate

- Avoiding extreme temperatures, such as with hot tubs

- Keeping the arm clean and dry; applying moisturizer daily

- Avoiding resting the arm below the heart or sleeping on the affected arm

- Wearing gloves when gardening or using household cleaners

- Avoiding carrying heavy over-the-shoulder bags or purses on the affected side

- Monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection (fever, swelling, redness, pain, and heat) and seeing a physician for evaluation immediately

(ACS, 2021g)

It is imperative that nurses and healthcare providers instruct patients on the above symptoms to report and precautionary measures to take both before and after surgery as well as reviewing this during treatments and follow-up appointments.

While there is no cure, treatment for lymphedema is available and is best started at the first sign of swelling. Healthcare providers and rehabilitation specialists can work with patients before surgery to focus on prehabilitation when possible and must be vigilant in assessing patients for any problems after surgery during follow-up appointments. Assessment may include asking questions about symptoms, quality of life, and activities; taking measurements on the affected arm; skin inspection; and palpation.

The goal of treatment is to decrease the swelling as much as possible and maintain the limb at its smallest size. This helps prevent or eliminate infections and minimize discomfort. Treatments include complete decongestive therapy, manual lymph drainage, and compression, as prescribed by a physical therapist, occupational therapist, or other certified lymphedema specialist.

Patients with post-treatment edema or early signs of lymphedema are referred to a lymphedema specialist to initiate evaluation and instruction on complete decongestive therapy, which includes four components:

- Manual lymphatic drainage. This is a specific massage technique that uses gentle and progressively directed manual (by hand) massage, following the direction of the natural flow of lymph. It is generally shown to produce excellent results.

- Compression bandaging techniques or wearing of compression garments. Compression bandages or garments are customized to the individual patient and can provide the specific level of support needed to reduce edema. Bandages or garments can be used on a regular basis to help keep swelling and symptoms under good control.

- Exercises to promote lymph drainage. Patients are taught by rehabilitation specialists to perform regular and specific exercises of the shoulder joint, as well as at the elbow, wrist, and hand.

- Skin care. Patients are instructed to keep their skin clean, dry, and hydrated with a gentle moisturizer. Daily inspection for any edema is encouraged. Patients are instructed to report any new swelling, heaviness, or pain to their healthcare provider right away, even if it has been a long period of time since treatment was completed.

(MSKCC, 2022)

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY AND LYMPHEDEMA

Occupational therapy services are an integral part of managing lymphedema treatment. Occupational therapists (OTs) require additional training to become lymphedema certified (CLT-LANA). Once certified, OTs may include the following interventions:

- Conducting baseline assessments and preoperative education on what to watch for and how to prevent postoperative lymphedema

- Ongoing screening and monitoring for any problems

- Education and training on postoperative therapeutic range-of-motion exercises as well as incorporating activities of daily living such as grooming and bathing

- Providing information on how to prevent lymphedema by modifying lifestyle habits and clothing and assessing occupational risks

- Providing treatment with manual lymph therapy

- Referring patients to other support programs

- Providing education on self-care management, including skin care, infection prevention, compression garments, and adaptive clothing

(AOTA, 2021)

RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY

Breast reconstruction is a surgical procedure performed by a plastic surgeon and may require a longer recovery than mastectomy alone. Reconstruction can be performed at the same time as a mastectomy (immediate reconstruction), or it can be done later (delayed reconstruction). Immediate reconstruction may not be possible if the tumor is advanced and radiation is recommended. With immediate reconstruction, chemotherapy treatments are usually delayed for at least two to three weeks after surgery.

Breast reconstruction may be contraindicated for women who have diabetes, smoke, are obese or very thin, or have blood circulation problems.

There are options available with reconstructive surgery, but they are not all appropriate for every candidate. Essentially, there are two categories:

- Implant-based: Reconstruction using a tissue expander inserted into the affected area of breast, which is then injected with saline over a period of months and later replaced with a silicone or saline-filled silicone implant

- Autologous tissue: Reconstruction using the patient’s own tissue (most commonly transferred from the abdomen or the buttocks) to create a new breast mound

(NCI, 2022)

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy particles or rays, which produce at least three main effects:

- Inducing apoptosis, or programmed cell death, by invoking the preexisting signaling cascade through radiation damage, which results in cell self-destruct

- Causing permanent cell-cycle arrest or terminal differentiation (i.e., blocking cancer cells from moving beyond a cell cycle, rendering them unable to proliferate)

- Inducing cells to die as they attempt cell division (i.e., damaging the DNA, which results in an unsuccessful mitotic phase and causes cell death)

There are several reasons radiation therapy is utilized in treating breast cancer:

- After breast-conserving surgery (BCS), to decrease local recurrence rate

- To reduce the risk of recurrence after mastectomy when:

- The breast tumor is >5 cm

- Axillary lymph nodes test positive for cancer cells

- Margins of the tumor site are narrow and test positive for cancer cells

- In recurrent disease, to control metastasis

- To palliate symptoms of metastatic disease

(NCCN, 2022a)

TYPES OF RADIATION THERAPY

The most common way radiation therapy (RT) is delivered in breast cancer patients is through external beam radiation. RT can be delivered in various schedules. A common schedule has been to deliver external beam radiation therapy once per day, five days per week, for five to six weeks starting approximately one month after surgery. If a patient is also receiving chemotherapy, radiation therapy is typically started three to four weeks after completion of therapy (ACS, 2021g).

The daily schedule can present a challenge for patients, especially if they have to travel a distance to reach an RT facility. Travel expense, transportation, employment issues, and even childcare can all contribute to difficulty in complying with the RT schedule. Scheduling radiation appointments early in the day or at the same time each day often assists patients with their work/life schedules. Many patients continue to work throughout radiation therapy. For patients with such concerns, a social worker can assist in developing the plan of care, encouraging the patient to seek assistance from friends and family and referring to local support groups.

Newer approaches such as hypofractionated radiation therapy (also called accelerated breast irradiation) administer larger doses over a shorter time span (three weeks versus five to six weeks) for patients with negative lymph nodes after BCS. The hypofractionated radiation schedule appears to be just as effective as standard therapy in preventing recurrence and is more convenient for patients (ACS, 2021g).

Another newer approach called 3D-conformal radiation therapy is given with special machines that deliver radiation to the localized area where the tumor was removed (tumor bed). This allows treatment to a targeted area with less damage to healthy tissue. Treatments are given twice a day for five days. This is considered to be accelerated partial breast irradiation (ASC, 2021g).

External beam radiation can also be given intraoperatively at the time a lumpectomy is performed on early-stage breast cancer. In this approach, a single, large dose of radiation is directed at the lumpectomy site before the incision is closed (ASC, 2021g).

In proton beam therapy, a particle accelerator generates a highly charged beam consisting of positively charged protons. The approximately 5-millimeter beam can be finely controlled in its width, height, and depth so that it is directed specifically within the three-dimensional contours of a breast tumor. Proton beam is being investigated as an adjuvant radiation therapy for early and locally advanced stages of breast cancer. While the role of proton beam is still being discovered, rapid technological advances are poised to improve outcomes for patients with breast cancer (Mutter et al., 2021).

Another form of radiation therapy is internal radiation, or brachytherapy. Brachytherapy uses radioactive pellets, seeds, wires, or catheters that are temporarily placed in the breast tissue adjacent to the cancerous area or in the space where the tumor was removed. This method is often used in conjunction with external beam RT to give an extra “boost” in patients after BCS.

Brachytherapy targets radiation only to the area of the breast around the location of the tumor prior to surgery (generally, the lumpectomy cavity, plus 1 to 2 centimeters beyond the surgical edge). Brachytherapy is given over a period of four to five days and minimizes radiation exposure to other parts of the body. The rationale behind breast brachytherapy is to intensify treatment to the area most at risk for recurrence. Brachytherapy has fewer side effects, better cosmetic results, and improved overall quality of life during the treatment period (ASC, 2021g).

SIDE EFFECTS AND LATE EFFECTS OF RADIATION THERAPY

Both short- and long-term side effects are possible with radiation treatment. The two most common short-term side effects are fatigue and skin reactions in the irradiated area. In most cases, neither effect is noticeable until at least halfway through the six weeks of treatment.

Fatigue is the most common side effect in women undergoing radiation treatment and may last for several weeks or months after treatment. The level and length of the fatigue is as varied as the individuals experiencing it. Patients are taught to anticipate some level of fatigue along with various strategies to conserve energy.

Skin reactions to radiation can range from a mild “sunburn” effect to severe rash and swelling. Patients are taught to protect the radiated skin from exposure to harsh soaps and lotions, to avoid sun exposure, and to protect their skin from extreme temperatures (such as a hot bath or hot shower). Other skin-related side effects may include skin irritation, soreness, peeling, blistering, and decreased sensation or hypersensation (NCI, 2021). Healthcare providers may prescribe or recommend topical ointments and medicated creams to help treat skin damage.

Patient self-care strategies for skin care include:

- Wash the radiated area gently with warm (not hot) water and a mild soap.

- Do not shower more than once per day; limit baths to twice weekly for less than 30 minutes per bath.

- Avoid rubbing, scrubbing, or scratching the skin.

- Be careful not to wash off the ink markings needed for radiation therapy.

- Wash off any lotions or creams from sites prior to RT, as their presence can intensify burns.

- Gently pat skin dry after bathing.

- Avoid deodorant or talcum powder on the radiated side.

- Wear soft clothes and use cotton sheets.

- Avoid adhesive tape, bandages, or other types of sticky tape on the treatment area.

- Avoid chlorinated swimming pools and hot tubs during radiation treatment.

- Always protect the radiated area from exposure to the sun or tanning beds, even after treatment ends.

- Promptly report pain, swelling, exudate, or other skin changes to one’s primary care provider.

More serious (uncommon) side effects include swelling in the arm, lung damage, nerve damage, heart damage, and increased chance of rib fracture (NCI, 2021).

There is a slight risk of developing pneumonitis (a transient lung inflammation) following chest-wall irradiation. The risk can be greater depending on the exact field that is radiated. Patients undergoing RT are instructed to report a persistent dry cough, shortness of breath on exertion, the inability to take a full breath, chest pain, fever, malaise, or weight loss. Lung problems can occur anywhere from four weeks to 12 months after treatment.

Other short-term side effects of internal radiation include redness, bruising, breast pain, infection, weakness, rib fracture, and breakdown of fat tissue in the breast (NCI, 2021).

Radiation therapy can also have serious long-term complications. As mentioned earlier, radiation therapy increases the risk of lymphedema, which is chronic and can appear even years after treatment.

Radiation therapy for breast cancer can also slightly increase the risk of secondary malignancies, including leukemia, lung cancer, a small risk of contralateral second breast cancer, esophageal cancer, or a rare type of cancer called angiosarcoma. These cancers may develop 10 or more years after treatment in the tissue that has been radiated (ACS, 2022b).

Systemic Therapies

Treatments for breast cancer also include systemic therapies, which use the body’s circulatory and lymphatic systems to deliver therapies directly to the site of disease at a cellular level. Systemic therapies can be used in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings or to treat cancer that has metastasized outside the original tumor site.

Systemic therapies include endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapies, biologics, and/or a combination of therapies.

ENDOCRINE THERAPY

Decades of research indicate that the hormone estrogen is linked to the development of a certain type of breast cancer and to the likelihood of its recurrence. That is why in the past, surgical removal of the ovaries (oophorectomy) often caused breast cancers to regress, and oophorectomy is still offered to estrogen receptor–positive (ER-positive) patients with extensive disease.

Today, however, the primary long-term treatment for ER-positive breast cancer is the use of drugs that interfere with the production of estrogen, which reduces the chance of recurrence or metastasis of ER-positive breast cancer. Two groups of drugs that affect estrogen production in the body are selective estrogen response modulators (SERMs) and aromatase inhibitors.

Options for premenopausal patients who are ER-positive include treatment with SERMs, ovarian ablation, or a combination of ovarian suppression in combination with SERMs. Aromatase inhibitors are also recommended for premenopausal women with metastatic ER/PR-positive breast cancer (after medical or surgical menopause) (NCCN, 2022a).

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modifiers

Selective estrogen receptor modulators include tamoxifen, raloxifene, and toremifene. SERMs stop estrogen from stimulating breast cancer cell growth by blocking the estrogen receptors.

Tamoxifen (Nolvadex) is the mainstay of hormone therapy for breast cancer and can be used in many ways, including:

- To treat women with invasive or noninvasive ER-positive breast cancer. Tamoxifen is used along with surgery to reduce the chance of recurrence. It can also reduce the risk of cancer in the opposite breast. Tamoxifen can be given either as neoadjuvant therapy or adjuvant therapy and is usually taken for five to ten years. For early-stage breast cancer, this drug is mainly used for women who have not yet gone through menopause.

- To treat women with advanced-stage ER-positive breast cancer. Tamoxifen can help slow or stop cancer growth and shrink tumors.

- To treat women who are at a higher risk for breast cancer. Tamoxifen can be used as a preventive medicine to lower the risk of developing breast cancer.

Unlike chemotherapy, tamoxifen does not cause neuropathy or mucositis, but it does have side effects that can alter quality of life and even be life threatening. The most common side effects are hot flashes, vaginitis, nonbloody vaginal discharge, induced menopause, sexual dysfunction, depression, and mood swings. While rare, in some patients tamoxifen can hasten the development of cataracts or cause fractures, blood clots in the lungs or legs, stroke, and/or endometrial (uterine) cancer.

Depending on the age of the patient and tumor characteristics, the oncologist may recommend chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy as well as tamoxifen. The preferred sequencing for tamoxifen is initiation of the medication after chemotherapy is complete (NCCN, 2022a).

Raloxifene (Evista) is a newer drug than tamoxifen. It was approved in 1997 to prevent osteoporosis after menopause. However, early studies of raloxifene also suggested that the drug reduced the risk of breast cancer without the risk of uterine cancer that tamoxifen carries, but with a similar risk of blood clots. Subsequent studies confirmed these findings, so raloxifene is sometimes prescribed to reduce the risk of breast cancer in women who do not have breast cancer but are at high risk for developing the disease and who are postmenopausal with an intact uterus.

Toremifene (Fareston) is indicated in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women with either ER-positive or unknown status. It is not likely to work well if tamoxifen has been used and stopped working.

Selective Estrogen Receptor Degraders (SERDs)

SERDs block and damage estrogen receptors with an anti-estrogen effect in the entire body.

Goseraline acetate (Zoladex) is used in pre- or perimenopausal women with ER-positive advanced disease to induce menopause. It is injected into the subcutaneous abdominal tissue either every 28 days or every three months if given in the depot form. Adherence to the treatment schedule is important with Zoladex, especially in the nondepot form. Long-term use may cause osteoporosis.

Fulvestrant (Faslodex) is indicated for postmenopausal women with metastatic ER-positive breast cancer that has failed first-line, anti-estrogen therapy. It is administered as an intramuscular (IM) injection once monthly and comes in a prefilled syringe.

Newer oral SERDs are also being developed. Elacestrant (Orserdu) gained FDA approval in 2023 for postmenopausal women or adult men with ER-positive, HER2-negative, ESR1-mutated advanced or metastatic breast cancer who have undergone at least one line of endocrine therapy. Elacestrant is an oral pill taken daily until no longer tolerated or disease progression.

Aromatase Inhibitors (AIs)

Aromatase is an enzyme produced in body fat and other tissue, particularly the breast. After menopause, when the ovaries no longer produce estrogen, aromatase converts hormones called androgens, produced by the adrenal glands, into estrogen. This conversion serves as the body’s main source of estrogen after menopause and therefore raises the risk of breast cancer and recurrence. For this reason, it is thought that excess body fat in postmenopausal women may increase the risk of breast cancer (ACS, 2021i).

AIs inhibit (block) the conversion of androgens to estrogens, thereby limiting the amount of estrogen that can reach cancer cells. This can lead to regression or stabilization of a tumor. However, AIs also act on other estrogen-sensitive tissues, which may account for some of the drugs’ side effects, such as muscle and joint pain and bone loss. Bone loss can increase fractures of the hip, spine, or wrist (ACS, 2021b). Additional side effects of AIs include hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and vaginal atrophy.

While tamoxifen is still an option for adjuvant endocrine treatment in postmenopausal women, AIs have been found to be more effective in preventing cancer recurrence in the first two years following breast cancer surgery. Aromatase inhibitors are not associated with the thromboembolic events and uterine cancers that are seen with tamoxifen (ACS, 2021b).

Currently, it is recommended that patients with ER/PR-positive breast cancer take an AI for at least five years. For those who do not tolerate or for other reasons do not want to take an AI, tamoxifen for at least five years is recommended (ACS, 2021b).

Three aromatase inhibitors have been approved by the FDA for use in advanced cancer: anastrozole (Arimidex), letrozole (Femara), and exemestane (Aromasin). Anastrozole has also been approved as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with hormone-responsive-positive breast cancer. This is an oral therapy taken daily. Aromatase inhibitors can increase the risk of osteoporosis; therefore, it is recommended that women have a dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan when treatment is initiated and continuing every two years to evaluate bone density (ACS, 2021b).

PREVENTING AND TREATING AI-INDUCED BONE LOSS

Zolendronic acid (Zometa), a bisphosphonate, and denosumab (Xgeva, Prolia), a monoclonal antibody, are both approved drugs used to prevent and/or decrease AI-induced osteoporosis and risk for bone loss in breast cancer patients.

Bisphosphonates work by inhibiting resorption of bone by osteoclasts and have been studied extensively in breast cancer patients. These drugs have also been shown to decrease risk of bone metastasis and may increase overall survival. Bisphosphonates are generally administered intravenously every six months for three years, for a total of six doses. Occasionally, bisphosphonates are administered orally to patients who have or develop osteoporosis.

Denosumab is a human monoclonal antibody that targets the RANK ligand (RANKL) protein, which acts as the primary signal promoting bone removal. By inhibiting the development and activity of osteoclasts, denosumab decreases bone resorption and increases bone density. Denosumab is also given every six months for three years (Eisen, 2022). Denosumab cannot be stopped without starting bisphosphonates, as there is a risk for rebound fractures.

Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may also be indicated in patients treated for breast cancer to aid with bone mineral density.

CHEMOTHERAPY

Administration of chemotherapy generally occurs after surgery for breast cancer; this is called adjuvant chemotherapy. However, patients with large tumors may receive chemotherapy before surgery to shrink the tumor and perhaps avoid a mastectomy; this is called neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Neoadjuvant therapy also allows for an early evaluation of the effectiveness of systemic therapy. In addition, neoadjuvant therapy may provide the opportunity to obtain tumor specimens and blood samples prior to and during the preoperative treatment. This has enabled researchers to identify tumor- or patient-specific biomarkers in order to plan appropriate targeted therapies (ACS, 2021j).

Statistically, chemotherapy treatment can reduce the relative risk of recurrence by about one fourth to one third. For example, a patient with a larger, more aggressive tumor and more lymph nodes involved might have a 75% chance of recurrence without chemotherapy. With chemotherapy, the statistical risk of recurrence might be reduced to around 50%. In contrast, a patient with a small tumor and negative lymph nodes might have a statistical risk of recurrence reduced from 12% to 8%. The higher the statistical risk of recurrence, the greater potential benefit from chemotherapy (NCCN, 2022a).

The medical oncologist generally quantifies a patient’s statistical risk of recurrence and the percentage of benefit the patient might expect from chemotherapy. This may be determined by pathology results and other information about the tumor, such as genomic information provided by the Oncotype DX test. This statistical analysis does not guarantee a particular outcome, and chemotherapy may have a greater or lesser effect on the risk of recurrence than predicted.

Common Treatment Regimens

Chemotherapy treatment is generally given in cycles of either every 21 or 28 days over the course of three months, six months, or one year, depending on the individual patient situation. The time between treatments allows the bone marrow to recover. At times, two or three different chemotherapy drugs are given in combination in order to increase effectiveness in eradicating cancerous cells (ACS, 2021j).

Oncologists have found that giving certain chemotherapy regimens closer together can lower recurrence rates and improve survival. Chemotherapy treatments are given as often as every two weeks with this regimen, called dose-dense chemotherapy. However, a dose-dense chemotherapy regimen can lead to more severe side effects and can be difficult to tolerate. Growth factors to help the white blood cell count recover may be given as well. Patients who are HER2-positive receive trastuzumab (Herceptin) on a weekly schedule, while receiving their chemotherapy every 21 days (ACS, 2021j).

In most situations, chemotherapy is most effective when combinations of one or more drugs are used. Many combinations are currently being used, and it is not clear that any single combination is the best. Clinical studies continue to compare current treatments with new agents and combinations.

| Name | Drugs |

|---|---|

| (ACS, 2021j; NCCN, 2022a) | |

| CMF | Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil |

| CAF (or FAC) | Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and 5-fluorouracil |

| AC | Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) |

| EC | Epirubicin (Ellence) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) |

| TAC | Docetaxel (Taxotere), doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) |

| AC-T | Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) followed by paclitaxel (Taxol) or docetaxel (Taxotere); trastuzumab (Herceptin) may be given with the paclitaxel or docetaxel for HER2/neu-positive tumors |

| CEF (or FEC) | Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), epirubicin (Ellence), and 5-fluorouracil; may be followed by docetaxel (Taxotere) |

| TC | Docetaxel (Taxotere) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) |

| For HER2/neu-positive tumors | |

| TCH | Docetaxel (Taxotere), carboplatin, and trastuzumab (Herceptin) |

| AC-TH | Doxorubicin (Adriamycin), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), paclitaxel (Taxol), and trastuzumab (Herceptin) |

| AC-THP | Doxorubicin (Adriamycin), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), paclitaxel (Taxol), trastuzumab (Herceptin), and pertuzumab (Perjeta) |

| TCHP | Docetaxel (Taxotere), carboplatin , trastuzumab (Herceptin), and pertuzumab (Perjeta) TH Paclitaxel (Taxol) and trastuzumab (Herceptin) |

Different chemotherapy regimens are associated with particular risks and side effects, so it is important that each patient be informed and educated about the potential side effects of the regimen the oncologist recommends in order to make an informed decision about treatment. An instructional session that includes the significant other and/or caregiver by a knowledgeable, experienced oncology nurse or practitioner is crucial before chemotherapy commences. Other patients who have been through chemotherapy can be helpful resources as well, together with local support groups or online blogs, to help patients anticipate and cope with potential side effects.

Side Effects of Chemotherapy

Most chemotherapy drugs used to treat breast cancer have toxic side effects. Nausea and vomiting, hair loss, and fatigue are the most common. Increased risk of infection and anemia due to bone marrow suppression are other commonly seen toxicities and can actually become dose-limiting. Chemotherapy-induced menopausal symptoms, neuropathy, and cognitive changes are also frequent complaints.

NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Despite advances in antiemetic therapies, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) remains one of the most feared and expected side effects of chemotherapy. Preventive use of antiemetic therapy is important because CINV may lead to reduced quality of life, increased use of healthcare resources, and challenges to treatment adherence.

Healthcare professionals can be proactive in teaching coping skills for CINV. It can be helpful for patients to eat small, frequent meals and avoid foods that are fried, high in fat, strong tasting, strong smelling, gas forming, spicy, or acidic.

It is vital that caregivers are aware of the risk factors for severe nausea (female gender, young age, and vomiting during previous chemotherapy treatment) and that the patient knows to contact the healthcare provider promptly if CINV is not well-controlled. Studies show CINV is most successfully treated with a preventive, proactive approach.

HAIR LOSS

Generally speaking, if hair loss occurs, it will begin about 10 to 20 days after chemotherapy treatment begins. It can affect not only scalp hair but also body and facial hair, although eyebrows and eyelashes can take much longer to fall out. It is important to explain that the scalp needs protection with either a hat or sunscreen when exposed to the sun and in order to minimize loss of body heat when it is cold.

Usually, hair regrowth begins about three to six weeks after chemotherapy is completed. It is not uncommon for hair to grow back a different color or texture (known as “chemo-curl”), but typically, after about a year, it returns to its previous state. For older patients, however, if their post-chemo hair growth is white or grey, it may stay that color indefinitely.

FATIGUE

Fatigue is the most commonly reported side effect of chemotherapy. It is also the most debilitating side effect, affecting all other areas of a patient’s life. This distressing symptom may or may not be associated with anemia. There is much research concentrated on the exact physiologic cause of cancer-related fatigue and ways to combat it.

It is important for healthcare providers to assess fatigue levels using a fatigue scale (much like a pain scale) in order to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions and to be alerted to the potential for more serious problems (i.e., disease recurrence or progression) if the fatigue level is high.

Strategies to cope with cancer-related fatigue include:

- Prioritizing tasks and activities in order of importance

- Delegating errands and household chores to family and friends

- Taking short rest periods (20–30 minutes or less) during the day when needed

- Planning activities that require higher energy during peak energy times

- Incorporating moderate exercise (e.g., walking)

- Avoiding caffeine, as it can interfere with sleep

- Developing a bedtime routine to aid in sleep

- Taking in adequate fluids, as dehydration can contribute to fatigue

- Eating a balanced diet; limiting high-fat and high-sugar foods

(Gebruers, 2019; MSKCC, 2021)

Patients may also be encouraged to seek ways to decrease stress, which can contribute to fatigue, through relaxation techniques, quiet music, guided imagery, massage, meditation, etc.

INFECTION

Chemotherapy attacks rapidly dividing cancer cells. Unfortunately, it affects normal rapidly dividing cells as well.

White blood cells, a vital part of the immune system, are some of the most frequently dividing cells in the body, so they can be profoundly impacted by chemotherapy. Low white blood cell count (neutropenia, or low neutrophils) can result in decreased resistance to infection in people who are receiving chemotherapy.

For this reason, patients on chemotherapy treatments must be diligent in avoiding infection. The number-one preventive measure they and those in their households can take is frequent and thorough handwashing. A good reminder to give patients is to be sure hand hygiene is performed before eating, food preparation, and contact with eyes, nose, or mouth, and after using the toilet, contacting pets, and gardening.

Patients should also avoid crowds and people (especially children) with active colds or infections. Avoiding pet waste, such as changing cat litter boxes, is also recommended. Other precautions include prompt attention to cuts/injuries and to any signs of infection, wearing gloves while gardening, washing fruits and vegetables before consumption, and avoiding raw or undercooked animal products or seafood.

General signs and symptoms to watch for related to neutropenia include fever, chills, sweating, sore throat or sores in the mouth, abdominal pain, cough, and shortness of breath.

LIBIDO, INFERTILITY, EARLY MENOPAUSE

Chemotherapy can affect sexuality, intimacy, and fertility. It can cause vaginal dryness, pain, and discomfort during sexual activity. Premenopausal patients may experience infertility and early menopause induced by chemotherapy. The younger the patient, the more likely their menstrual periods will return when chemotherapy is finished. The closer they are to the age of natural menopause, the more likely chemotherapy will bring about menopause, with hot flashes, vaginal dryness, mood swings, and sleep disturbances. There may also be increased risk of osteoporosis.

Many of these factors, along with body image changes due to surgery and radiation, may impact a patient’s sexuality and intimacy. It is important to recognize and initiate a discussion about fertility and sexual changes as part of pretreatment education to address issues patients may face or are already experiencing. By normalizing the subject of intimacy and approaching it as a quality of life issue, healthcare providers may find patients become more comfortable in discussing their concerns. Patients with breast cancer should be encouraged to visit with a specialist in treating menopausal symptoms and sexual dysfunction that occurs as a result of the cancer or its treatments.

COGNITIVE EFFECTS

Many patients who have received chemotherapy treatment notice cognitive changes, or “chemo brain”—the forgetfulness, loss of concentration, and decrease in mental functioning that often accompany chemotherapy. Consequences of cancer treatment—such as low blood counts, fatigue, infection, menopause, poor nutrition, and sleep issues—may also trigger cognitive symptoms. The medical community recognizes these symptoms as real. Cognitive changes that begin during cancer treatment may last months and even years after treatment is complete.

CHEMOTHERAPY-INDUCED PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY (CIPN)

Chemotherapy drugs used to treat breast cancer, including taxanes and platinum agents, can cause damage to the nerves, leading to peripheral neuropathy. The most common symptoms associated with CIPN are sensory neuropathies, including paresthesias (burning, tingling, and numbness) and pain starting in the fingers and toes, which can spread proximally. CIPN can begin weeks to months after initial treatment and reach a peak at or after the end of treatment. In some cases, the pain and paresthesias completely resolve after treatment is stopped. However, in most cases, CIPN is only partially reversible and can be permanent. CIPN may be prevented with the use of frozen gloves/socks worn during drug infusion with weekly paclitaxel.

TARGETED THERAPIES

Targeted therapy is a type of treatment that uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells without harming normal cells. Monoclonal antibodies, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, and PARP inhibitors are types of targeted therapies used in the treatment of breast cancer (ACS, 2022c).

- Lapatinib (Tykerb) is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks the HER2 protein as well as other proteins inside tumor cells. It may be combined with other drugs to treat patients with HER2-positive breast cancer that has progressed after initial treatment with trastuzumab. When treatment with trastuzumab fails for patients with HER2-positive metastatic disease, lapatinib may improve progression-free survival. Lapatinib works by inhibiting intracellular cell signaling.

- Pertuzumab (Perjeta), like trastuzumab, is a monoclonal antibody that attaches to the HER2 protein. Pertuzumab targets a different part of the HER2 protein and can be used in combination with docetaxel and trastuzumab for first-line treatment in advanced-stage breast cancer patients.

- Ado-trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) is a monoclonal antibody linked to a chemotherapy drug. This combination is called an antibody-drug conjugate. This drug is used to treat recurrent HER2-positive breast cancer.

- Naratinib (Nerlynx) is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks the HER2 protein as well as other proteins inside tumor cells. It is used to treat patients with early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer after initial treatment with trastuzumab.

- Palbociclib (Ibrance) is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor used with the drug letrozole to treat recurrent breast cancer that is ER positive and HER2 negative. It is used in postmenopausal women whose cancer has not been treated with hormone therapy.

- Ribociclib (Kisqali) is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor used with letrozole to treat recurrent or metastatic breast cancer that is hormone receptor positive and HER2 negative.

- Abemaciclib (Verzenio) is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor used to treat hormone receptor–positive and HER2-negative breast cancer that is advanced or metastatic. It may be used alone or with other drugs.

- Everolimus (Affinitor) is a targeted therapy (for advanced HER2-positive or -negative cancers) that blocks mTOR, a protein in cancer cells that promotes growth. By blocking this protein, everolimus can stop cancer tumors from developing blood vessels and limit growth. Everolimus is usually given along with exemestance (Aromasin) in women who have disease progression while on either letrozole or anastrazole.

- Olaparib (Lynparza) is a PARP inhibitor used to treat patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. PARP inhibitor therapy is also being studied for the treatment of patients with triple-negative breast cancer.

- Talazoparib (Talzenna) is a PARP inhibitor used to treat patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations with HER2-negative advanced-stage or metastatic breast cancer.

(ACS, 2022c)

BIOLOGIC THERAPY/HER-2 DIRECTED THERAPY

Rather than destroying cancer cells (and other cells), biologic therapy interrupts the tumor process. In 1998, research into biologic therapies showed promising results, and the FDA approved the drug trastuzumab (Herceptin) for metastatic breast cancer.

Fifteen to twenty percent of newly diagnosed breast cancers have amplification or overexpression of the HER2 oncogene (ACS, 2022c). Trastuzumab was a major breakthrough in the treatment of this usually aggressive tumor type, improving progression-free, disease-free, and overall survival.

Trastuzumab is a targeted approach to treatment that is classified as a monoclonal antibody. Originally FDA-approved for use in metastatic breast cancer, trastuzumab is now also approved and used as standard treatment in the adjuvant setting in combination with chemotherapy. Patients with HER2-positive breast cancer with nodal involvement and patients with HER2-positive tumors >2 cm without nodal involvement are appropriate candidates for first-line adjuvant treatment with trastuzumab. Patients with metastatic disease that is HER2-positive can also benefit from trastuzumab, sometimes as monotherapy, with very good results (NCCN, 2022a).

There are several types of epidermal growth factor receptors, but HER2 overexpression is most highly associated with breast cancer growth. Trastuzumab interrupts this cancer cell division by deactivating the protein on the surface of the cell that fuels its growth, in essence acting as a “false key” in the lock that fits the receptor but does not turn. The attached monoclonal antibody then also signals for cell destruction by the patient’s own immune system.

Side Effects and Contraindications

Because trastuzumab works differently than cytotoxic chemotherapy, it is not associated with the same side effects. Instead, the most common side effect appears to be infusion reactions—including shaking, chills, fever, headache, abdominal pain, and dyspnea, especially with the first dose—which can appear during infusion and up to 24 hours after infusion. Other possible but less common infusion reactions are vomiting, dizziness, rhinitis, hypotension, and rash.

Additional considerations are asthenia (loss of strength), left ventricular (LV) cardiac dysfunction, diarrhea, and increased incidence of leukopenia, anemia, neutropenia, and infection when used in combination with chemotherapy. Rarely, severe hypersensitivity reactions occur, in which case trastuzumab should be discontinued indefinitely. Also, pulmonary toxicities such as interstitial pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are uncommon but documented in patients receiving trastuzumab.

Because of the cardiac toxicity potential, patients who are to receive trastuzumab therapy are required to have either a multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan or a cardiac echocardiogram to determine baseline LV ejection fraction prior to start of therapy and at regular intervals throughout treatment. This monitoring is especially important for patients who also receive anthracyclines and/or chest irradiation. Patients must be educated to report urgently upon noticing any signs and symptoms of heart failure (ACS, 2022c).

Oncologists have specific guidelines for when to hold trastuzumab and when and how to restart therapy as testing shows improvement of LV function, although not standardized. Patients who have existing heart failure prior to treatment should not be started on trastuzumab, and those who show clinical signs of heart failure while on therapy should have therapy discontinued.

IMMUNOTHERAPY

Immunotherapy is a type of treatment that uses the patient’s own immune system to target the cancer. These substances are made both by the body or in a laboratory and used to direct the body’s defense system against the cancer. This type of treatment is also called biologic therapy.

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) are PD-1 inhibitors used to treat metastatic breast cancer. PD-1 is a protein on the surface of T-cells that helps to keep the body’s immune system in balance. When PD-1 attaches to a protein on the surface of a cancer cell called PDL-1, it triggers the T-cells to attack the cancer cell (ACS, 2021k; NCCN, 2022a).

While generally well tolerated, immunotherapy can have significant adverse reactions that require prompt evaluation and treatment. Immune-related adverse events (IrAEs) occur when the over-activated immune system targets normal tissue and organs of the body. These events can occur anywhere in the body, but more common areas are the lungs (pneumonitis), skin (dermatitis), and thyroid (thyroiditis). Generally, the treatment for IrAEs is high-dose steroids with long, closely monitored tapers. Depending on the significance of the IrAE, therapy may need to be held or permanently discontinued (ACS, 2021k).

Integrative Care

Integrative therapies generally refers to strategies or treatments used in conjunction with conventional medicine as a complement to prescribed cancer treatment. The goal of these therapies is not to cure cancer but to work in concert with traditional cancer treatment to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

It is estimated that up to 80% of patients with cancer and long-term survivors of cancer use integrative therapies during and after cancer treatment (ASCO, 2022b). Many people with cancer choose one or more integrative therapies to reduce the side effects of chemotherapy and radiation, relieve pain, boost their immune system, improve quality of life, reduce stress, and promote healing. Integrative treatments can also help patients in coping with their cancer, as it can increase their sense of empowerment and wellness.

Integrative therapies may include nutritional supplements, dietary changes, herbal supplements, essential oils, exercise, yoga, tai chi, guided imagery, mindfulness meditation, massage, or acupuncture used in addition to conventional medicine. Nutritional supplements are the most frequently chosen therapy.

It is essential for healthcare professionals to obtain a complete list of all supplements a patient is utilizing to avoid possible interactions with or detrimental action against conventional cancer treatments. Assessment and monitoring throughout the illness trajectory is very important in protecting patient safety.

Unlike conventional medicine, which treats a specific problem by standard methods—such as surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy—integrative therapy views the patient as a whole entity and the body as more than the sum of its parts. More recently, this holistic approach has been referred to as mind-body medicine or integrative medicine.

Alternative therapies are unconventional treatments used in place of conventional, mainstream medicine. By definition, alternative therapies have not been scientifically proven, often have little or no scientific basis, and in some cases have even been disproved. Alternative therapies are too numerous and too controversial to address fully in this course. However, some common examples of alternative therapies for the treatment of cancer that patients may hear about include high-dose vitamin C, laetrile, and other herbal remedies.

Patients should be warned about the potential harm as well as the possible negative financial impact of using alternative therapy in place of evidence-based therapies exclusively for the treatment of cancer. The use of alternative therapies in place of conventional medicine may decrease the chance of remission or cancer cure. It is important to encourage a discussion of any and all treatment decisions in a nonjudgmental manner so as to keep the lines of communication open.