UNDERSTANDING A BREAST CANCER DIAGNOSIS

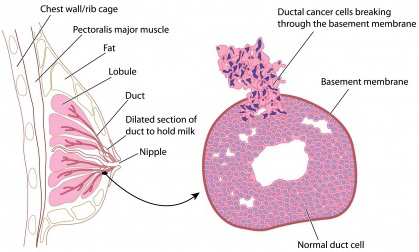

The breast is made up of lobules (glands that produce milk), ducts (tiny tubes that carry milk from the lobules to the nipple), and stroma (connective and fatty tissue that surrounds the lobules and ducts, including blood and lymph vessels). Most of the lymph vessels in the breast lead to lymph nodes under the arm (axillary nodes).

Breast cancer normally arises in the epithelial cells that line the ducts and lobes of the breast, which are in constant turnover. These cells are generated continuously by a basal membrane and normally divide, migrate, and differentiate in a tightly controlled process. Cancer forms when internal (genetic alterations) or external (e.g., environmental and hormonal) factors interfere and the cells undergo an abnormal spectrum of changes, from hyperplasia to preinvasive to invasive and metastatic cancer.

The most common sign of breast cancer is a painless, hard lump with irregular edges. However, two thirds of lumps in the breast are not cancerous; they may be fluid-filled cysts, fibroadenomas (benign tumors), or pseudo lumps.

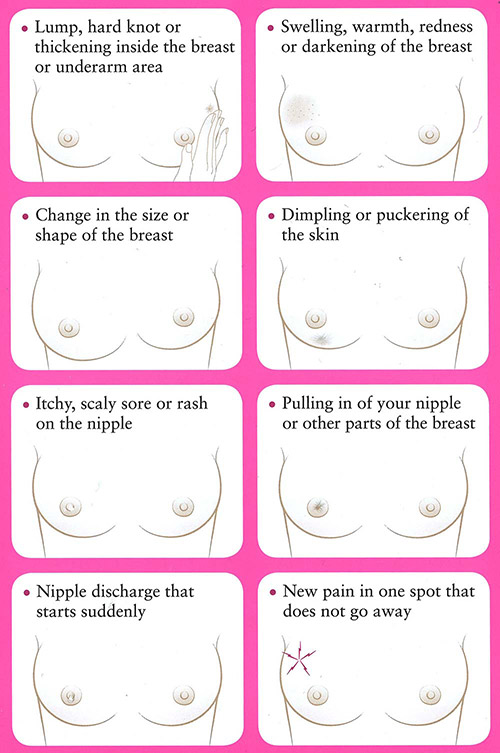

Warning signs of breast cancer may not be the same for everyone. Women should be aware of changes in the look and feel of their breasts as well as changes in the nipple or discharge from the nipple. Possible warning signs of breast cancer include:

- Lump, hard knot, or thickening inside the breast or underarm area

- Swelling, warmth, redness, or darkening of the breast

- Change in the size or shape of the breast

- Dimpling or puckering of the skin

- Itchy, scaly sore or rash on the nipple

- Pulling in of the nipple or other parts of the breast

- Nipple discharge that starts suddenly

- New pain in one spot that does not go away

Warning signs of breast cancer. (© 2016, Susan G. Komen. Used with permission.)

Diagnostics

The process of diagnosing breast cancer may include a complete physical exam, assessment of risk factors, mammographic evaluation, other imaging tests, laboratory tests, and biopsy of the suspicious area. Biopsy is the most definitive step in the process, establishing whether the abnormality is benign (noncancerous) or malignant (cancerous) since no definitive diagnosis can be made without microscopic evaluation. If the diagnosis is breast cancer, the pathologist defines the type of cancer and whether it is invasive or noninvasive (in situ).

BIOPSIES

A biopsy involves removal of a small sample of tissue in the suspicious lesion for analysis in the laboratory. There are different types of biopsies, and each has advantages and disadvantages. Biopsies are performed by surgeons, radiologists, and/or pathologists and evaluated by cytopathologists (pathologists who specialize in cancer). Along with identifying cancerous cells, a biopsy can provide information about the type of cancer as well as hormone receptor status (ER, PR, and HER2), which is important in the process of treatment planning.

There are two categories of biopsies for breast tumors: needle biopsies and surgical (open) biopsies.

Needle biopsies are generally outpatient procedures and include:

- Fine-needle aspiration biopsy

- Ultrasound-directed needle biopsy

- Vacuum-assisted core biopsy

- Stereotactic core-needle biopsy

Surgical biopsies include:

- Needle-localization biopsy

- Excisional biopsy

IMAGING

Imaging tests are used to evaluate whether the breast cancer has metastasized (spread to any other parts of the body). This includes tissue surrounding the tumor, regional or distant lymph nodes, or other organs. The lungs are a common site for breast cancer metastases. Therefore, a chest X-ray is generally ordered during the diagnostic process. CT scans of the liver and brain are recommended only if metastases are suspected in those areas. Bone scans are done only if laboratory tests suggest the presence of bony metastases or if there are other known areas of metastases coupled with clinical presentation of bony pain. PET scans have proved more effective in detecting soft tissue metastases than metastatic bone lesions. However, the PET/CT combination is replacing CT in detecting soft tissue metastases because of its increased effectiveness (ACS, 2021c).

LABORATORY AND BIOMARKER TESTS

If a breast lesion is large and/or locally advanced—especially if any lymph nodes are involved—then the suspicion factor for distant metastases is raised, and they must be ruled out. The provider may order a number of blood tests to assess for signs of metastasis. For example:

- Serum alkaline phosphatase, which may signal liver or bone metastases

- Calcium levels, in which hypercalcemia may indicate bone metastases

Biomarkers are substances (i.e., hormone receptors or growth factors) that are present in cancer cells and help the cancer grow and spread. Testing for biomarkers can indicate specific characteristics of tumors that may help determine which treatment would be most effective in treating and preventing recurrence of the cancer.

The standard of care is to test breast tumors for hormone receptor status, including estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR), along with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu) oncogene at the time of initial diagnosis (ACS, 2021a). This information is now used in staging breast cancer. Cancer treatments target these specific biomarkers by inhibiting the growth factors or blocking the hormone receptor to stop or slow the cancer growth.

Another important feature of the cancer pathology is the Ki67 expression. This marker is associated with cell proliferations and growth and has been shown to correlate with metastasis and the clinical stage of breast cancer (Brown et al., 2022). Knowing the Ki67 can help the physician understand how aggressive the cancer might be.

Types of Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is categorized based on pathology and the degree to which the cancer has spread. If the cancerous cells are confined to the ducts or lobules, the cancer is called noninvasive or in situ. Breast cancer that has spread through the walls of the ducts or lobules into the surrounding fatty and connective tissue is referred to as invasive or infiltrating.

INVASIVE DUCTAL CARCINOMA

Invasive ductal carcinoma accounts for about 80% of cases and is the most common form of breast cancer (ACS, 2021d). Originating in the ducts of the breast, invasive ductal carcinoma breaks through the wall of the duct into the breast tissue. It commonly forms a hard lump, which feels much firmer than a fibroadenoma (benign breast lump). On a mammogram, it usually appears as a mass edged with tiny spikes (spiculation).

Cross section of breast with detail of ductal carcinoma. (Image © Peter Lamb; used with permission under license. May not be copied or downloaded without permission from 123RF Limited.)

INVASIVE LOBULAR CARCINOMA

Invasive lobular carcinoma is less common and originates in the lobules of the breast, where the milk is produced before it enters the ducts of the breast. It generally does not form a nodule or lump but spreads out and forms an area of thickening and fullness. Lobular carcinoma is also more difficult to see on a mammogram than ductal carcinoma. A number of research studies have linked invasive lobular breast cancer with use of hormone replacement therapy (Vinogradova et al., 2020).

TRIPLE-NEGATIVE BREAST CANCER

Treatment for breast cancer is often directed by characteristics of the cancer pathology (as discussed later in this course). People whose tumor pathology are estrogen receptor-negative, progesterone receptor-negative, and HER2/neu-negative are said to have triple-negative breast cancer. This is a rare subtype of breast cancer more common among younger people and those of African or Hispanic ancestry. It is highly aggressive, with distinct patterns of metastasis, and nonresponsive to hormone therapy or targeted therapy.

Brain and other visceral metastases are more common in triple-negative breast cancer than are bone metastases. Treatment for triple-negative breast cancer is usually surgery followed by traditional chemotherapy. Clinical trials continue to study new targeted therapies and immunotherapy for this type of cancer (CDC, 2021).

INFLAMMATORY CARCINOMA

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is the most malignant form of breast cancer and accounts for about 1%–5% of all breast cancers in the United States. Some experts think IBC may be more common but underreported because it can be difficult to diagnose (ACS, 2022a). IBC is usually classified as stage 3B or stage 4, indicating that it has metastasized to distant sites at the time of diagnosis.

This aggressive subtype may be mistaken for an infection because it is characterized by swelling, pain, and reddened, warm skin over the breast. The inflamed appearance is caused by invasion of cancer cells into the subdermal lymphatic channels. If antibiotics do not rapidly change the appearance, biopsy is performed.

Standard treatment for IBC is chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery to remove the cancer. Radiation is given post surgery. Additional chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or targeted agents may also be recommended as treatment. This is especially true if IBC is advanced (ACS, 2022a).

Like triple-negative breast cancer, IBC is more common in young African Americans. It is also more commonly found in overweight or obese women.

Once a uniformly fatal disease with only an 18-month survival rate from time of diagnosis, IBC can now be treated more effectively. Recent data reports a 41% 5-year survival rate for IBC (ASCO, 2022a).

PAGET’S DISEASE OF THE BREAST

Paget’s carcinoma is a very rare cancer, accounting for only 1% of breast cancer cases. It primarily affects the nipple, presenting as itching or burning with superficial erosion or ulceration. In some cases, there is no breast mass. Like inflammatory breast cancer, Paget’s disease of the breast is often misdiagnosed, in this case as dermatitis, delaying proper diagnosis.

If cancerous changes are confined to the nipple, the prognosis is excellent. If a breast mass is present, the cancer may have spread to the axillary nodes or beyond. Treatment may include lumpectomy or simple mastectomy, depending on the extent of disease. Lumpectomy with removal of the nipple and areolar complex followed by radiation therapy is recommended to reduce the risk of recurrence (ACS, 2021f).

BREAST CANCER DURING PREGNANCY OR LACTATION

Breast cancer during pregnancy or breastfeeding is rare, but it can occur. Even though the tumor may be felt, both the patient and their primary care provider may mistake it for normal pregnancy-related changes in the breast, delaying diagnosis. This delay means that in two thirds of cases, the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes before it is discovered.

Depending on the stage of the pregnancy at the time of diagnosis, some patients may choose to terminate the pregnancy before beginning treatment. Others may choose to have a mastectomy during pregnancy and follow up with chemotherapy after the baby is born. However, studies have shown chemotherapy can be delivered safely during the second and third trimesters. Radiation treatment is not given during any stage of pregnancy due to the high risk of fetal harm.

Understandably, younger patients who have not started or completed their families may be concerned about their subsequent fertility, as well as increased mortality by becoming pregnant after breast cancer. Most research so far has shown that pregnancy is possible and safe for both the fetus and the mother after early breast cancer treatment in young women without increasing the risk of recurrence. It is important for patients to discuss fertility prior to treatment in order to plan for best outcomes.

Staging

Staging describes the extent of cancer in the body. The primary elements are based on whether the cancer is invasive or noninvasive, the size of the tumor (T), lymph node involvement (N), and metastasis (M) to other parts of the body. The stage of a cancer (on a scale of 1 to 4, with 4 being the most advanced) describes how advanced the disease is and helps determine the course of treatment. Many breast cancers today are detected at stage 1 or 2. In situ cancer, usually ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), is called Stage 0. Within a stage, an earlier letter (a) means a lower stage within that number.

The most widely used staging system for breast cancer—the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system—was updated in 2018 to include seven key pieces of information. (These are also referred to as the pathologic prognostic stage group.) The treatment team uses AJCC staging to evaluate the stage of the disease and plan appropriate treatment. This is now quite complex and takes into account many individual factors (ACS 2021a; Giuliano et al., 2018).

AJCC staging includes the following elements to formally stage breast cancer:

- Size of the tumor (T)

- Spread to nearby lymph nodes (N)

- Spread (metastasis) to distant sites in the body (M)

- Estrogen receptor (ER) status

- Progesterone receptor (PR) status

- HER2/neu (HER2) status

- Grade of the cancer (G), based on how normal or abnormal the cells appear when examined microscopically