MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT OF OBESITY IN ADULTS

Effective management, as with all chronic medical conditions, must be based on a partnership between a highly motivated patient and a team of health professionals, which may include a physician, psychologist, psychiatrist, advanced practice nurse, social worker, case manager, pharmacist, physical therapist, occupational therapist, dietitian, and other specialists, depending on the person’s comorbidities. Scientific evidence indicates that multidisciplinary programs reliably produce and sustain modest weight loss between 5% and 10% for the long-term.

Management strategies include:

- Lifestyle interventions using diet and physical activity

- Behavioral therapy, including assessing readiness for change

- Pharmacotherapy

- Surgery

Lifestyle Intervention for Adults

Initially, management requires the recognition that medical advice to “just eat less and exercise more” is not effective for patients to succeed at losing weight and maintaining that weight loss. Most individuals who are overweight or obese have already tried self-help approaches well before medical intervention is considered.

The patient’s weight management history can be a starting point in determining the choice of a treatment plan, which should begin with comprehensive lifestyle management, including diet, physical activity, and behavior modification. This plan should include:

- Self-monitoring of caloric intake and physical activity

- Goal setting

- Stimulus control

- Nonfood rewards

- Relapse prevention

WEIGHT-LOSS GOALS

An individual’s body weight and body fat are steadfastly regulated, and this is the basis of the challenge in losing weight and maintaining weight loss. Because of this, current thinking in the medical management of obesity has moved from a goal of massive weight loss to one of eliminating obesity-related comorbidities or reducing them to a minimum. Data previously suggested that approximately 10% of body weight loss in persons who are obese is associated with substantial health benefits. Newer guidelines indicate that clinically meaningful health improvements can be seen with weight loss in the range of 2% to 5% (Hamdy, 2022).

The weight-loss goal for each patient must be individualized; however, a reasonable goal in the setting of a medical treatment program is approximately 1 to 2 pounds per week. Factors that are considered in setting a weight-loss goal include the weight of other family members as well as the patient’s cultural, ethnic, and racial background. There is evidence that greater weight loss can be achieved with a culturally adapted weight-loss program than with a more general health program.

DIET

Current findings indicate that many types of diet can be successful in losing weight. The best predictor of success is dietary adherence. Therefore, providers are advised to recommend diets to improve adherence according to patient preference.

Diet composition is important, but the key factor in promoting weight loss is a negative energy balance. Conventional diets can be classified broadly into two categories: 1) balanced, low-calorie diets (or reduced portion sizes) and 2) diets with different macronutrient compositions such as low-fat, high-protein, or low-carbohydrate diets (Perreault & Delahanty, 2021).

Low-Calorie and Reduced-Portion Diets

Balanced, low-calorie diets and reduced-portion diets are those that dietitians and other weight-management professionals most commonly recommend. These diets underlie most of the commercial weight-loss programs, such as Weight Watchers, Take Off Pounds Sensibly (TOPS), and Overeaters Anonymous (OA). They are useful for short-term weight loss, but none of them are associated with reliable sustained weight loss. Diet-induced weight loss can result in increased levels of hormones that increase appetite. After successfully losing weight, these circulating levels of hormones do not decrease to levels prior to the weight loss, thus requiring long-term strategies to prevent obesity relapse.

Low-calorie diets involve reducing daily caloric intake by 500–1,000 kcal/day to a level of 800–1,800 kcal/day. They are associated with a mean weight loss of 1 to 2 pounds per week. A low-calorie diet may consist of a mix of meal replacements and regular foods divided among three or more meals throughout the day. Alcohol, sodas, most fruit juices, and highly concentrated sweets are generally prohibited or reduced to a minimum (Hamdy, 2022).

Potential complications of these diets can include:

- Vitamin deficiency

- Starvation ketosis

- Electrolyte derangements

- Cholelithiasis

Low-calorie versions considered healthy include:

- Mediterranean diet:

- High level of monosaturated fat, such as olive oil

- Fish

- Nuts

- Moderate consumption of alcohol, mainly as wine

- High consumption of vegetables, fruits, legumes, beans, and grains

- Moderate consumption of milk and dairy products, mostly cheese

- Low intake of meat and meat products

- Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH):

- 6–8 servings of grain/day

- 4–5 servings of fruit/day

- 4–5 servings of vegetables/day

- 2–3 servings of fat-free or low-fat dairy/day

- 6 or fewer 1-ounce servings/day of lean meats, poultry, and fish

- 4–5 servings of nuts, seeds, and legumes per week

- 2–3 servings fats and oils/day

- <5 servings per week of sweets and added sugars

- Less than 25% dietary intake from fat

Reduced-portion diets may be based on regular, everyday foods; by participation in a structured weight-loss program (e.g., Jenny Craig, Nutrisystem); or by incorporating products such as meal-replacement shakes, prepackaged meals, and frozen entrees (e.g., Lean Cuisine, Healthy Choice). These have adequate amounts of major macronutrients based on the food pyramid from the USDA and recommended daily allowances (RDAs). Alcohol, sodas, most fruit juices, and highly concentrated sweets are calorie dense and nutrient deficient and are generally prohibited or reduced to a minimum (Hamdy, 2022).

Very low-calorie diets (VLCDs) are those with energy levels between 200 and 800 kcal/day, while those below 200 kcal/day are termed starvation diets. Although once popular, starvation diets are not recommended for treatment of obesity. Very low-calorie diets should only be undertaken under a doctor’s supervision and paired with specialty foods to prevent nutrient deficiencies.

VLCDs are associated with profound initial weight loss of up to 3 to 5 pounds per week, much of which is from loss of lean tissue mass in the first few weeks, and have been shown to be superior to conventional diets for long-term weight loss. Most VLCDs use meal replacements such as formulas, soups, shakes, and bars instead of regular meals in order to ensure adequate intake of nutrients. VLCDs are “drastic measures” recommended only for adults who are obese and need to lose weight quickly for health reasons. However, if prescribed for children, adolescents, or elderly patients, special precautions should be taken. The use of VLCDs is contraindicated in the following settings:

- Pregnancy

- Protein-wasting states

- Clinically significant cardiac, renal, hepatic, psychiatric, or cerebrovascular disease

- Any other chronic diseases

VLCDs are often used before weight-loss surgery and are only recommended for a period of up to 12 weeks. Compliance beyond a few weeks is poor, and close supervision is required. Adverse effects can include hair loss, skin thinning, hypothermia, cholelithiasis, ketosis, vitamin deficiency, electrolyte derangement, and emotional problems.

Diets with Different Macronutrient Compositions

Macronutrients refer to carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. Some diets emphasize manipulation of these macronutrients in order to promote weight loss. There is moderately certain evidence that, over six months, most macronutrient diets result in modest weight loss and substantial improvements in cardiovascular risk factors. At 12 months, the effects on weight reduction diminishes and blood pressure improvements largely disappear (Long et al., 2020).

Low-Carbohydrate Diets

While all low-carbohydrate diets reduce the overall intake of carbohydrates, there is no clear consensus on what defines a low-carb diet. However, a daily limit of 20–57 grams of carbohydrates is typical with a low-carb diet.

Low-carbohydrate approaches to weight loss are based on the hypothesis that lowering insulin, a critical hormone that produces an anabolic, fat-storing state, improves cardiometabolic function and results in weight loss. Studies thus far have shown low-carb diets, and specifically ketogenic diets, to be superior to other dietary approaches in producing rapid weight loss for the first 6 to 12 months. A low-carbohydrate diet includes:

- Lean meats, such as sirloin, chicken breast, or pork

- Fish

- Eggs

- Nonstarchy vegetables, e.g., leafy green vegetables, cauliflower, and broccoli

- Nuts and seeds, including nut butter

- Oils, such as olive, coconut, and rapeseed

- Some fruits, such as apples, blueberries, and strawberries

- Unsweetened dairy products, including plain whole milk and plain Greek yogurt

When there is a lower intake of carbohydrates, the intake of fat and protein generally increases to compensate for the reduction. It is believed that low-carb diets produce rapid weight loss compared to other diets because fats and protein increase satiety and produce less accompanying hypoglycemia, which reduces hunger and overall food intake.

Types of popular-named, low-carbohydrate diets include:

- Atkins Diet

- Low-carb Paleo

- Whole30

- Low-carb Mediterranean

- South Beach

- The Zone

The ketogenic diet, a specific version of low-carb and high-fat diet, restricts carbohydrates to induce nutritional ketosis (but does not produce metabolic ketosis) and typically limits carbs to 20–50 gm/day. Restricting carbs to under 50 gms induces glycogen depletion and ketone production from the mobilization of fat stored in adipose tissue. Side effects of this type of diet include:

- Constipation due to low fiber intake

- Muscle cramps

- Halitosis (bad breath)

- Risk of “keto flu,” which may include headaches, fatigue, brain fog, irritability, lack of motivation

(Oh et al., 2021)

Low-Fat Diets

Low-fat dietary guidelines recommend a reduction in daily intake of fat to less than 30% of energy intake per day, and very low–fat diets provide less than 10% to 15%. The main premise behind this recommendation is that fat provides a higher number of calories per gram (9) compared to proteins and carbs (4). People who reduce their calorie intake by eating less fat do lose weight, and although the average loss is small, it is considered relevant for health. A low-fat diet may consist of:

- Whole grains, vegetables, and fruit at every meal

- Beans, peas, lentils

- Limited intake (6 ounces per day) of lean meat, fish, poultry without skin, and egg whites

- No more than 3 teaspoons of fat per day (vegetable oils)

- Low-fat or fat-free sweets and snack foods in moderation

- Fat-free or low-fat dairy

(Perreault & Delahanty, 2021)

Restricting fat too much can lead to health problems in the long term, as fat plays a key role in the production of hormones, nutrient absorption, and cell health. Consequences of low-fat eating can include:

- Flaky, dry skin

- Mood imbalances

- Hormone imbalances

- Constant hunger and cravings

- Poor vitamin absorption

- Very low-fat diets have been linked to a higher risk of metabolic syndrome

Types of popular-named low-fat diets include:

- Ornish diet

- Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC) diet

- Engine2

(Long et al., 2020)

High-Protein Diets

High-protein diets have been recommended for obesity treatment because they can help build lean muscle (which increases the number of calories burned throughout the day) and are more satiating and stimulate thermogenesis. High-protein diets may also improve weight maintenance. Like low-carbohydrate diets, high-protein diets can produce a state of ketosis. Some high-protein foods include:

- Legumes

- Dried beans

- Salmon

- Potatoes

- Meat

- Fish

- Eggs

- Dairy

- Peanut butter

- Tofu

(Perreault & Delahanty, 2021)

Popular-named high-protein diets include:

- Protein Power diet

Intermittent Fasting

Intermittent fasting is an eating plan that cycles between periods of fasting and eating on a regular schedule. There are many different intermittent fasting schedules one can follow, such as eating only during an eight-hour period each day and fasting for the remainder. Or, it may involve eating only one meal a day two days a week. After hours without food, the body exhausts its sugar stores and starts burning fat. During times when the person is not eating, water and zero-calorie beverages are permitted.

It is recommended that individuals who are undertaking intermittent fasting for weight loss use the Mediterranean diet as a guide for the types of foods to be eaten.

Research to date has found that intermittent fasting:

- Boosts working and verbal memory

- Improves blood pressure and resting heart rates

- Improves physical endurance

Intermittent fasting is not recommended for:

- Children and teens under age 18

- Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding

- People with diabetes or blood sugar problems

- Those with a history of eating disorders

(Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2022)

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Physical inactivity is a primary contributor to obesity and is often targeted for intervention because it is modifiable at the individual level. Creating a negative energy balance by decreasing calorie consumption and increasing activity is a common strategy in the management of overweight and obesity. Physical activity is an important lifestyle behavior associated with long-term weight loss and prevention of weight gain following initial weight loss.

Weight loss by diet without physical activity, especially in older people, can increase frailty due to age-related losses in bone density and muscle mass. Adding aerobic and resistance activity counters such loss.

Physical activity prevents obesity by:

- Increasing total energy expenditure

- Decreasing fat around the waist and total body fat

- Slowing the development of abdominal obesity

- Helping build muscle mass, which increases energy burned even when at rest

- Reducing depression and anxiety, which can help with motivation

(Harvard T.H. Chan, 2022a)

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services makes the following recommendations for physical activity:

- Moderate-intensity aerobic activity: 150 minutes per week of moderate activity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous activity. This can be spread out over the course of the week in sessions at least 10 minutes long.

- Strength training: At least twice a week, no specific amount of time is specified.

- Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity: 60 minutes or more daily for children and adolescents ages 6–17 years.

(CDC, 2019; CDC, 2020)

For those who are keeping track of calories taken in and expended, it is helpful to know approximately how many calories are burned during a chosen activity in 30 minutes (see table below).

| Activity | 125-pound person | 155-pound person | 185-pound person |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Harvard Medical School, 2021) | |||

| Sleeping | 19 | 22 | 26 |

| Sitting/Reading | 34 | 40 | 47 |

| Cooking | 57 | 70 | 84 |

| Food shopping | 85 | 106 | 126 |

| Low impact aerobics | 165 | 198 | 231 |

| High impact aerobics | 210 | 252 | 294 |

| Walking 3.5 mph | 107 | 133 | 159 |

| Hiking cross country | 170 | 216 | 252 |

| Biking 12–13 mph | 210 | 252 | 294 |

| Running 5 mph | 240 | 288 | 336 |

| Swimming | 180 | 216 | 252 |

THE ROLE OF PHYSICAL THERAPY

Physical therapists are an important part of the multidisciplinary team working with individuals with obesity. Physical therapists assist patients to become more physically active by teaching ways to exercise without causing pain and that are enjoyable. Therapists determine an appropriate treatment program for each individual that includes aerobic exercise and strength training.

Physical therapists also help patients explore the underlying reasons for their behaviors and to identify barriers to developing more healthy habits. They work with the patient to set individualized, realistic goals and assist the patient to stay with the program. The following are ways in which physical therapists work with bariatric patients:

- Pain reduction. By designing a personalized exercise program, the therapist can help with the performance of activities with the least amount of pain. Although the person may experience pain with activity, the activity itself may help reduce pain.

- Cardiovascular health. Physical therapists develop aerobic exercise programs that are heart-healthy, elevate metabolism, and burn more calories.

- Movement. Physical therapists work with patients to help restore normal range of motion of the joints, progressing from passive exercises to active exercises.

- Muscle strength. Physical therapy helps to improve muscle strength by addressing muscle weakness and developing gentle and low-impact resistance forms of weight training to improve overall strength and relieve joint discomfort. Because muscle burns more calories than other body tissues, muscle-building exercises can benefit weight-loss efforts.

- Flexibility and posture. The physical therapist works with patients to gently stretch tight major muscles and to improve and maintain proper posture, which is essential in performing difficult activities with ease, less discomfort, and respiratory function.

(APTA, 2021)

Behavioral Modification

Changing behavior—especially long-term, habitual patterns—and getting oneself to do something different even when it is known to be the best thing to do, depends on an individual’s mindset. Mindset refers to the belief in one’s limitations. A fixed mindset focuses on what is known and the belief that basic abilities and talents are fixed traits that cannot be changed. A growth mindset focuses on improving what and how one does things. In order to lose weight and keep it off, people often must learn to think differently about what they eat, when they eat, and how they eat.

ASSESSING READINESS TO CHANGE

Efforts aimed at behavioral change begin with the clinician’s determination of a patient’s readiness to change as well as the readiness of parents and families of obese children and adolescents to change. One model for assessing such readiness is the Transtheoretical Model, which explores the individual’s feelings, awareness, judgments, perceptions, and behavior, and describes the process of change using five stages.

- Precontemplation. Individuals in this stage have no intention of changing or taking action within the near future. People are often uninformed about the consequences of overweight and obesity, they may have failed in the past to make changes or lose weight, or they may avoid seeking any information that would help change behavior. People in this stage often underestimate the pros and place more emphasis on the cons of changing behavior.

- Contemplation. The person is considering making changes within the next 6 months and is aware of both the positive effects of making change and the negative effects of failing to change. Even with this recognition, people may still feel ambivalent toward making changes.

- Preparation (Determination). An individual in this stage of readiness is determined to take action within the next month and has usually begun to prepare a plan of action, such as a weight-loss or exercise program. At this stage they believe changing their behavior can lead to a healthier life. Individuals in this stage require assistance in the development and implementation of specific action plans and in setting realistic goals.

- Action. The person in this stage of readiness has made significant modifications in behavior and lifestyle over the past 6 months or longer and intends to keep moving forward. Assisting a person can include providing problem-based learning experiences, support, and feedback.

- Maintenance. The person has made significant modification in behavior and lifestyle and has actively worked to prevent a relapse for more than 6 months. The individual is confident that change can be maintained. At this stage, it is important to continue to provide support, assist with problem-solving, positively address slips and relapses, and employ reminder systems or performance support tools.

(LaMorte, 2019)

INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

Interventions aimed at behavioral modification are considered essential in the management of the patient who is overweight or obese. Behavioral modification methods can be used either alone or in conjunction with other treatments, working to create goals, helping to maintain goals that have already been achieved, preventing possible relapses, and managing difficult situations.

Behavioral modification interventions include face-to-face contact and are often conducted in group sessions, which may be available at local hospitals, through commercial programs, or in office settings. While some patients might prefer individual therapy, the group setting may be more cost effective, and there is insufficient evidence to conclude that one is better than the other. All interventions use similar strategies, which include the following elements:

- Collaborative setting of realistic and achievable goals, which is meant to increase motivation and adherence. These goals are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Reasonable, and Time-bound (SMART) and should be within a patient’s control.

- Self-monitoring of food intake, weight, and activity, which is the most important step in successful behavior therapy. Self-monitoring slows down decision-making, allowing time to make healthier choices and alerting the individual about overconsumption and nutritional content of foods. Tools for self-monitoring can include keeping food diaries and activity records, internet applications, smartphone applications, and digital scales for self-weighing and recording.

- Stimulus control, which alters the person’s environment to help make better choices. Participants are educated in selecting fresh fruits and vegetables; preparing easy-to-eat, lower-calorie foods; placing them prominently in the refrigerator or on the counter; and removing less-healthy foods from the home. Stimulus control also includes setting the environment so the individual can concentrate on eating.

- Eating style, which involves slowing down the eating process to give time for physiologic signals for fullness to arise. Practicing “mindful eating” allows one to concentrate on tastes and textures of food and savor what is being eaten by chewing more slowly. Other techniques might involve leaving the table briefly during a meal and drinking water between bites or just prior to the meal.

- Portion control and meal planning, which provide a defined meal structure and can result in greater weight loss than the absence of such a structure. Use of portion-control plates or meal replacement are examples.

- Regular weighing as a self-monitoring strategy. This has been recommended in some studies. Concerns have been raised that regular weighing might lead to anxiety and weight regain, but this has not been observed in a systematic literature review.

- Increasing physical activity. Along with self-monitoring, increasing physical activity is a key element in successfully losing weight.

- Nutrition education and meal planning with a registered dietitian for assessment of knowledge and preferences.

- Social support enhancement to improve long-term weight loss. Behavioral programs that include strong family support provide both short- and long-term benefits.

- Other behavioral tools may include:

- Cognitive restructuring, such as changing self-talk (see below)

- Problem-solving, such as managing food intake in difficult situations

- Assertiveness training, such as learning to say “no”

- Stress reduction, by identifying and reducing stressors that are triggers for eating

MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING (MI)

While behavioral interventions provide a variety of strategies for change, motivational interviewing addresses the specific challenges of motivation, confidence, treatment readiness, ambivalence, and resistance. It is an approach that has also been shown to be successful for individuals with substance abuse disorders.

MI assumes that behavior change is affected more by motivation than by information and that no lasting change will be achieved unless the patient sees the need to change. MI is person-centered and goal-directed, and it increases the person’s motivation for commitment to behavioral change. The hallmark of MI is working with and through a person’s ambivalence about making a change and recognizing that it is the patient who decides whether and how to change.

The core principles of MI are:

- Expressing empathy

- Supporting the person’s self-efficacy

- “Rolling” with resistance

- Developing discrepancy

MI has four fundamental processes that describe the flow of interaction. These include:

- Engaging: Establishing a productive working relationship

- Focusing: Both patient and practitioner agree on a shared purpose (negotiating/collaborating)

- Evoking: Exploring and assisting the patient to find their own “why” of change

- Planning: Providing support and exploring the “how” of making change

MI requires four communication skills that support and strengthen the process of eliciting “change talk.” Change talk are statements that the person makes that indicate being in favor of change. These skills include:

- Asking open-ended questions

- Affirming

- Reflective listening, mirroring

- Summarizing

(MINT, 2021; Ingersoll, 2022)

(See also the “Case” on motivational interviewing later in this course.)

TECHNOLOGY AND BEHAVIORAL CHANGE

Technology can also be enlisted to enhance the success of behavioral change efforts. One example, Mobile health (mHealth), with its portable, easily accessible, and ubiquitous nature, is used to monitor and promote weight loss by changing behavioral factors that contribute to a healthy lifestyle. It is supported by devices such as phones, tablets, personal computers, personal digital assistants, biosensors, and others to track and monitor diet and physical activity. Text messages are used to provide reminders or encourage certain behaviors.

MHealth has shown positive results in both adult and childhood obesity. Use of this technology provides education, clinical decision support, health promotion and awareness, remote monitoring and data collection/analysis, and integrated care and diagnostic support.

Another example, eHealth, involves internet-based programs such as web-based interactive voice response systems, a virtual world, and internet-based virtual coaching to provide an interactive platform for communication and education on diet, physical activity, and exercise.

The type of technology used has been found to be associated with weight loss. MHealth shows more instances of statistically significant association with weight loss, as compared to telehealth/telemedicine and eHealth (House et al., 2019).

THE ROLE OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

Occupational therapists treat patients for the prevention and management of obesity, including helping with weight-loss efforts and adaptations for occupational challenges caused by obesity. Occupational therapists assist patients who are obese in making necessary lifestyle changes by focusing on health promotion, disease prevention, remediation, adaptation, and maintenance. Outcomes often include increased participation, increased ease when performing activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living that require physical activity and endurance, improved self-esteem, and decreased symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Occupational therapists enhance the person’s functional abilities in the following areas and manner:

- Activities of daily living, including strategies for maintaining good hygiene

- Supporting increased physical endurance

- Offering strategies for safe mobility in the home and in the community

- Teaching ways to conserve energy and to simplify work

- Instructing in the use of proper body mechanics to avoid injury

- Monitoring and maintaining skin integrity

- Recommending and assisting with adaptive equipment and methods to facilitate instrumental activities of daily living

- Home modification to promote participation in activities, improve environmental access, and ensure safety

- Assisting with setting routines for healthy food selection, shopping, and meal preparation

- Assisting with the establishment of sleep routines, relaxation, and positioning to increase comfort and promote adequate rest

- Providing wellness groups for patients and families to facilitate health promotion and social support

- Teaching coping strategies for management of pain, stress, and anxiety

- Addressing sexual health concerns

- Assisting individuals to participate in the community by identifying appropriate businesses and social gatherings

- Assisting individuals in making task and environmental modifications to maintain participation in roles and occupations at current body weight, and to accommodate weight management

(Dieterle, 2018)

Pharmacology

There are only a few drugs available for the treatment of obesity, and their effectiveness is limited to palliation rather than cure. Benefits fade when they are discontinued. All medications carry more risks than diet and physical activity interventions, and medications are used only in those patients for whom the benefit justifies the risk. They are not used during pregnancy or when breastfeeding.

Weight-loss drugs are considered for patients with a BMI >30 or a BMI >27 with a serious medical condition related to obesity (e.g., diabetes, hypertension).

Weight-loss drugs may not be effective for everyone. When used as part of a diet and exercise plan, typical weight loss is 5%–10% of body weight over a 12-month period.

Currently, there are three major categories of drugs used to manage obesity:

- Anorexiants are drugs that act on the brain to suppress appetite. They have a stimulant effect on the hypothalamic and limbic regions of the brain that control satiety.

- Stimulants are drugs that increase dopamine, which accelerates the autonomic nervous system and results in an increased energy expenditure.

- Lipase inhibitors impair the gastrointestinal absorption of ingested fat, which is then excreted in the stool.

| Drug | Category | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|

| *Approved for long-term use. (Perreault, 2022; Hamdy, 2022; Mayo Clinic, 2020a; Anderson, 2021) |

||

| Phentermine (Adipex, Lomaira) | Anorexiant and stimulant | Increased blood pressure and heart rate, insomnia, nervousness, restlessness, dependence, abuse or withdrawal with long-term use |

| Diethylpropion | Anorexiant and stimulant | Constipation, restlessness, dry mouth |

| Gelesis100 (Plenity)* | Absorbs water, increases fullness. Considered a medical device but functions as a medication | Diarrhea, abdominal distension, infrequent bowel movements, constipation, abdominal pain, flatulence |

| Phentermine and topiramate ER (Qsymia)* | Anorexiant, decreases binge eating behaviors | Constipation, restlessness, dry mouth, increased blood pressure and heart rate, insomnia, nervousness, restlessness, dependence, abuse or withdrawal with long-term use |

| Liraglutide subcutaneous injection (Saxenda)* | Anorexiant, increases satiety | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, headache, heartburn, fatigue, dizziness, stomach pain, gas, dry mouth, low blood sugar in type 2 diabetes, increased lipase |

| Buproprion and naltrexone (Contrave)* | Anorexiant, decreases cravings | Nausea, vomiting, headache, fatigue, constipation, dizziness, insomnia, dry mouth, diarrhea, increased blood pressure, anxiety, tremor, hot flush, unusual taste |

| Orlistat (Alli OTC, Xenical)* | Lipase inhibitor | Oily spotting, flatulence, fecal urgency, soft stools, fecal incontinence; vitamin A, D, E, and K deficiency |

| Semaglutide (Wegovy)* subcutaneous injection | Anorexiant, increases satiety | Nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, headache, fatigue, dizziness, bloating, belching |

| Setmelanotide (Imcivree)* | Anorexiant, for patients 6 years and older with obesity due to three rare genetic conditions | Injection site reactions, skin hyperpigmentation, headache, gastrointestinal side effects, spontaneous penile erections in males and adverse sexual reactions in females, depression and suicidal ideation |

| Phendimetrazine (Bontril PDM) | Anorexiant | Dizziness, dry mouth, difficulty sleeping, irritability, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation |

Medical Devices

Considered medical devices, hydrogels are orally administered products. These are taken twice daily prior to meals, and expand in the stomach and intestines to create a sensation of fullness. They are not systematically absorbed and are eliminated in the stool. Hydrogels are indicated for use as weight management aids for adults with a BMI of 25–40 and are to be used in conjunction with diet and exercise. There is no restriction on how long the product can be used for weight management (Perreault & Apovian, 2021).

Weight Loss Surgical Procedures

Bariatric surgical procedures are increasingly common around the world. It is estimated that there were 394,432 bariatric procedures performed worldwide in 2018, the majority of which were performed in the United States and Canada. Surgical procedures for obesity are major, life-changing events. An individual who is considering bariatric surgery must undergo an evaluation to determine if the health benefits of surgery outweigh the potentially serious risks, and if the person is medically and psychologically able to undergo such procedures.

Candidates for bariatric surgery must meet at least one of the following criteria:

- BMI ≥40 or ≥100 pounds overweight

- BMI ≥35 and at least one obesity-related comorbidity (type 2 diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea, other respiratory disorder, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, osteoarthritis, lipid abnormality, gastrointestinal disorder, heart disease)

- Inability to achieve a healthy weight loss sustained for a period of time with prior weight loss efforts

It is recommended that surgery be performed by a board-certified surgeon with specialized experience/training in bariatric and metabolic surgery and at a center that has a multidisciplinary team of experts for follow-up care (ASMBS, 2022a).

Bariatric surgical procedures are contraindicated in those with:

- Untreated major depression or psychosis

- Uncontrolled and untreated eating disorders

- Current drug and alcohol abuse

- Severe cardiac disease with prohibitive anesthetic risks

- Severe coagulopathy

- Inability to comply with nutritional requirements, including lifelong vitamin replacement

Bariatric surgery in patients over 65 years is controversial but is considered when comorbidity is severe. Bariatric surgery for patients younger than 18 years is becoming more common for severe obesity (Lim, 2022).

TYPES OF BARIATRIC SURGERY

Bariatric surgical procedures cause weight loss by restricting the volume of food the stomach can hold, by causing malabsorption of nutrients, or by a combination of the two. They are performed with small incisions using minimally invasive surgical techniques (laparoscopic and robotic surgery). These advancements result in a better overall experience with less pain, fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, and a faster recovery. The operations are extremely safe, with complication rates that are lower than more common operations such as cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, or hip replacement.

The goal of the surgical procedures is to modify the stomach and intestines in order to treat obesity and related diseases. The operations may make the stomach smaller and also bypass a portion of the intestine. This results in less intake of food and changes how the body absorbs food for energy, resulting in decreased hunger and increased satiety.

After bariatric surgery, around 90% of patients lose 50% of excess body weight and keep this extra weight off long-term. In large, scientific studies of hundreds of thousands of patients, weight-loss surgery has been shown to lower a person’s risk of death from any cause by over 40% (ASMBS, 2020).

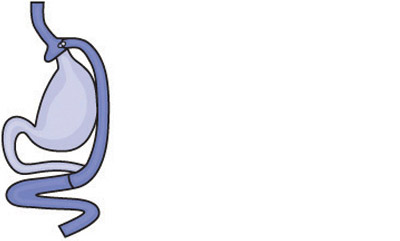

Gastric Bypass (Roux-en-Y)

The gastric bypass combines both restrictive and malabsorption approaches. The surgically created stomach pouch is smaller and able to hold less food, which means fewer calories are ingested. Also, the food does not come into contact with the first portion of the small intestine, and this results in decreased absorption.

The operation involves sealing off the upper section of the stomach from the lower section and then connecting the upper stomach directly to the bottom end of the small intestine. The procedure is completed by connecting the top portion of the divided small intestine to the small intestine further down so that stomach acids and enzymes from the passed stomach and first portion of the small intestine will eventually mix with the food.

Gastric bypass (Roux-en-Y). (Source: National Institutes of Health.)

With this procedure, weight loss usually exceeds 100 pounds or about 65%–70% of excess body weight and about 35% of BMI. Weight loss generally levels off in one to two years, and a regain of up to 20 pounds from the weight loss nadir to a long-term plateau is common. Gastric bypass is considered irreversible but has been reversed in rare cases.

Advantages:

- Reliable and long-lasting weight loss

- Effective for remission of obesity-associated conditions

Disadvantages:

- Technically more complex procedure and difficult to reverse

- More vitamin and mineral deficiencies than other procedures

- Risk for small bowel complications and obstruction

- May increase the risk of alcohol disorder

- Risk of developing ulcers, especially with NSAID or tobacco use

A significant risk for this procedure is dumping syndrome, which involves food emptying too rapidly from the stomach into the intestines before it is properly digested. Approximately 85% of people who have this procedure develop some dumping. Symptoms include nausea, bloating, pain, sweating, weakness, and diarrhea, and are often triggered by sugary or high-carbohydrate foods (Saber, 2021b; NIH, 2020).

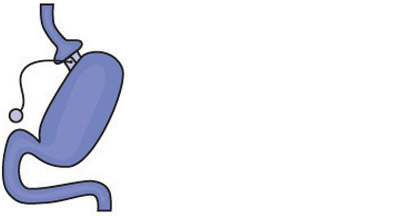

Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band

This is a restrictive procedure that involves the placement of an adjustable silicone band with an inner inflatable balloon around the top of the stomach, creating a small pouch that allows for a full feeling after eating a small amount of food (approximately one ounce). The balloon is filled with sterile saline solution, and the size of the opening from the pouch to the rest of the stomach can be adjusted as needed to reduce side effects and improve weight loss by injecting or removing the saline through a plastic tube that runs from the balloon to a small port placed under the skin.

Gastric banding. (Source: National Institutes of Health.)

Advantages:

- Lowest rate of complications early after surgery

- Done laparoscopically

- No diversion of stomach or intestines

- Patients go home the day of surgery

- The band can be removed if needed

- Has the lowest risk for vitamin and mineral deficiencies

Disadvantages:

- Band may need several adjustments and monthly office visits during the first year

- Slower and less weight loss than with other surgical procedures. (The impact on obesity-related diseases and long-term weight loss is less than with other procedures, and its use, therefore, has declined over the past decade.)

- Risk of band slippage or damage to the stomach over time (erosion)

- Requires a foreign implant to remain in the body

- Has a high rate of need for re-operation

- Can result in swallowing problems and enlargement of the esophagus

(Saber, 2021b; NIH, 2020)

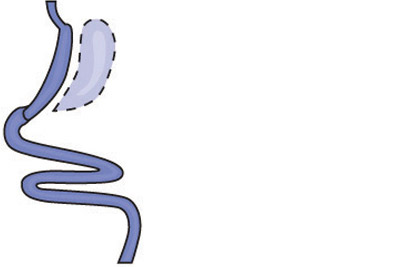

Gastric Sleeve

Gastric sleeve, also known as vertical sleeve gastrectomy, involves removal of 80% of the stomach, leaving a narrow tube or sleeve the size and shape of a banana, which is then connected to the intestines. This restricts the amount of food that can fit in the stomach, creating a feeling of fullness. Removal of part of the stomach also affects gut hormones and other factors such as gut bacteria that may affect both appetite and metabolism. This surgical procedure is not reversible.

Gastric sleeve. (Source: National Institutes of Health.)

Advantages:

- Technically simple, with shorter surgery time

- Can be performed in certain patients with high-risk medical conditions

- May be performed as the first step for patients with severe obesity

- May be used as a bridge to gastric bypass or SADI-S procedures

- Offers effective weight loss and improvement of obesity-related conditions

Disadvantages:

- Nonreversible

- May worsen or cause new-onset reflux and heart burn

- Has less impact on metabolism compared to bypass procedures

- Risk of long-term vitamin deficiencies

(Saber, 2021b)

Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch (BPD-DS)

This is a malabsorption procedure with two components: 1) a surgery similar to the gastric sleeve creates a small tubular stomach pouch, and 2) the duodenum is divided just past the outlet of the stomach. A segment of the distal small intestine is then brought up and connected to the outlet of the newly created stomach pouch, so that when the person eats, food passes through the tube and empties directly into the last segment of the small intestine. This second surgery redirects food to bypass roughly three quarters of the small intestine. The bypassed section is then reattached to the first part of the small intestine, allowing bile and pancreatic enzymes necessary for the breakdown and absorption of protein and fat to mix with food.

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. (Source: National Institutes of Health.)

This procedure is more involved than a gastric bypass but can result in even greater and more rapid weight loss. Much of the stomach is removed. However, what remains is larger than the pouches formed during gastric bypass or banding, and larger meals may be eaten with this surgery. The BPD-DS is considered to be the most effective approved metabolic operation for the treatment of type 2 diabetes.

Advantages:

- Among the best results for improving obesity

- Affects bowel hormones to cause less hunger and more fullness after eating

Disadvantages:

- Slightly higher complication rates than other procedures

- More complex surgery, requiring more operative time

- Highest malabsorption and greater possibility of vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies

- Reflux and heart burn can develop or worsen

- Risk of looser and more frequent bowel movements

(Saber, 2021b; ASMBS, 2021b)

Single Anastomosis Duodenal-Ileal Bypass with Sleeve Gastrectomy (SADI-S)

SADI-S is the most recent procedure to be endorsed by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. It is similar to BPD-DS, but the SADI-S is simpler and takes less time to perform, as there is only one surgical bowel connection.

The operation begins the same way as the sleeve gastrectomy, making a smaller tube-shaped stomach. The first part of the small intestine is divided just after the stomach, and a loop of intestine is measured several feet from its end and is then connected to the stomach.

When the patient eats, food goes through the pouch and directly into the latter portion of the small intestine. Food then mixes with digestive juices from the first part of the small intestine, allowing enough absorption of vitamins and minerals to maintain healthy levels.

Advantages:

- Offers good weight loss with less hunger, more fullness, blood sugar control, and diabetes improvement

- Simpler and faster to perform than gastric bypass or BPD-DS

- Excellent option for a patient who already had a sleeve gastrectomy and is seeking further weight loss

Disadvantages:

- Vitamins and minerals are not absorbed as well as in sleeve gastrectomy or gastric band

- Newer operation with only short-term outcome data

- Potential to worsen or develop new-onset reflux

- Risk of looser and more frequent bowel movements

(ASMBS, 2021a)

OTHER SURGICAL INTERVENTIONS

Intragastric Balloon Systems

These temporary devices are saline-filled silicone balloons that limit how much the stomach can hold, making the person feel fuller faster. There are three FDA-approved systems available. Two of these devices are placed endoscopically, while the other is swallowed. All three are removed endoscopically in six months.

An intragastric balloon may be an option for a person who:

- Has a BMI of 30–40 and one or more obesity-related comorbid conditions

- Has failed weight reduction with diet and exercise alone

Side effects and adverse events include nausea, vomiting, reflux, balloon migration, balloon intolerance, balloon leak, and intestinal or stomach perforation.

Balloons are typically filled with saline that is dyed blue, so if the patient’s urine turns blue or green, a leak should be suspected. This requires immediate medical attention, as the balloon would then be at risk for migrating and causing an intestinal obstruction. One of the devices (ReShape) is a two-balloon device so that if one breaks, the second balloon can prevent migration (Perreault & Apovian, 2021; Lim, 2022).

BARRIERS TO BARIATRIC SURGERY

Bariatric surgery is expensive. Even though patients may spend only two days in the hospital, these operations require the use of expensive, high-technology equipment as well as advanced nursing and surgical training. The average cost of gastric bypass surgery in the United States from 2020–2022 was $24,288, but there is a big cost difference between the states, ranging from $15,300 in Arkansas to $57,500 in Alaska.

| Type of Procedure | Average Price without Insurance |

|---|---|

| Gastric bypass | $24,288 |

| Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band | $15,180 |

| Gastric sleeve | $19,228 |

| Gastric balloon | $8,248 |

| Duodenal Switch | $27,324 |

The decision to pursue a surgical solution for treatment of obesity is often one taken by middle- to upper-income patients, since most low-income people cannot pay the cost for these procedures.

Many disabled obese patients have their healthcare coverage through Medicare. Obesity-related illnesses are primary reasons for disability coverage under Medicare. Medicare officials are very aware of the increased cost of treating all of the comorbid illness associated with obesity. Up until recently, Medicare had a clause stating that “obesity is not an illness” in their policy statement. This clause was recently deleted, with the implication that obesity therefore must be considered an illness.

Nearly all private insurance carriers in the past accepted the guidelines for weight-loss surgery. However, the recent explosion in the number of surgical procedures has resulted in many carriers adding qualifiers, such as 6 or 12 months of a continuously medically supervised diet. Most patients seeking weight-loss surgery have experienced years of failed diet treatments, but these attempts are rarely associated with written documentation and therefore do not qualify.

Precertification has become a complicated, long-term process often requiring a full-time staff person. Because bariatric surgical procedures are complex and associated with potentially serious complications, malpractice coverage has been increasingly difficult to obtain and very expensive. This increased overhead has driven many surgeons to drop out of HMOs and accept only patients with out-of-network coverage. These patients, however, are likely to pay a portion of the surgeon’s fee out-of-pocket.

After-surgery costs must also be considered. Nutritionist appointments are often out-of-pocket or negotiated before surgery. These can range from $50 to $100 per visit. Also, gastric bypass patients typically lose weight very fast and must be prepared to purchase new clothing. Long-term costs include lifelong nutritional supplements which can total $50/month (Obesitycoverage, 2020; PMPH, 2022).

THE ROLES OF OCCUPATIONAL AND PHYSICAL THERAPY IN BARIATRIC SURGERY

Occupational therapists provide lifestyle modification interventions to reduce weight before surgery and improve postsurgical outcomes. Occupational therapists also assist patients with occupational changes following surgery, including new habits and routines required when eating much smaller quantities of food, taking supplements, building and maintaining strength through physical activity, and social eating. Occupational therapy lifestyle interventions are also beneficial for patients who experience weight gain after the initial loss (Dieterle, 2018).

Physical therapists assist in the management of patients who are candidates for bariatric surgery. Therapists help prepare patients for the surgery and recovery by developing and instructing them in individualized preoperative and postoperative programs. Preoperatively, therapy may involve strength training and aerobic conditioning. Postoperative programs often begin with deep breathing and lower-extremity exercises to gently increase strength and aerobic conditioning. Physical therapists help to minimize pain, regain motion and strength, and return to normal activities as soon as possible (APTA, 2021).

CASE

Eric, Age 63

Eric is a 63-year-old man with type 2 diabetes who is referred by his primary care physician to the Kensington Bariatric Center for evaluation for bariatric surgery. The bariatric center is staffed by a team of obesity specialists that includes internists, registered dietitians, nurses, and a psychologist, all of whom are involved in a comprehensive evaluation of the patient.

Eric’s medical history indicates that his current medications include 70 units of NPH insulin before breakfast and 70 units before dinner, Metformin 850 mg twice a day, atorvastatin, nifedipine, aspirin, and allopurinol. He has sleep apnea but is not currently using his continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine. His reported morning glucose levels are between 100–130 mg/dl, hemoglobin A1C level is 6.1% (within normal limits), and his triglyceride level is 201 mg/dl. He weighs 342 pounds, is 5 feet 6 inches tall, and has a BMI of 55.2.

Eric reports that he became obese as a child and that he has gained weight every decade since. He is currently at his highest adult weight, and there are no indications that medications or medical complications contribute to his obesity. His family history reveals that his father, two of his sisters, and one of his daughters are also obese.

Eric describes his past weight-loss to have included both commercial and supervised medical weight-loss programs. He has been unable to sustain any weight he lost on these programs after a few months of discontinuing them. He has been to weight-loss sessions with a registered dietitian and has also taken part in a hospital-based, dietitian-led, group weight-loss program, where he lost weight. But again, he regained it all. He has been on many self-directed diets throughout the years but has never lost any significant weight while on them, and whatever weight he did lose, he once again regained.

A food intake history reveals that Eric eats three meals a day, with dinner being the largest. He sometimes eats between meals, especially if there is food available at his workplace. He eats a snack before bedtime to avoid hypoglycemia. He eats in restaurants once or twice each week but does not frequent any fast-food places. He does not drink alcohol. He admits to binge eating on occasion, even when not hungry, and attributes this to stress.

Eric is a widower who recently began a new relationship. He and his girlfriend have known each other for many years, and she is normal weight. He reports that both he and his girlfriend are concerned about his weight and his diabetes, and he is now willing to consider weight-loss surgery.

Following his evaluation, it is determined that Eric meets the criteria for surgery according to current clinical guidelines because he has clinical severe obesity (BMI ≥40 with comorbid conditions), has failed with less invasive methods of weight loss, and is at high risk for obesity-associated morbidity/mortality. He is found to have no contraindications for surgery.

Eric attends an orientation session where he learns about his surgical options, is given a description of the procedures, including their risks and possible complications, and is encouraged to ask questions. He is referred to the surgeon for evaluation, and it is decided that he will pursue the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. He is set up for a surgical date and also encouraged to lose weight before the surgery.

Eric does well after surgery, eats without difficulty, and reports feeling no hunger. At two months post surgery, his fasting and pre-dinner blood glucose levels have been consistently less than 120 mg/dl, with no other diabetes medications required.

One year following surgery, Eric’s weight is 254 pounds, a loss of 88 pounds, and he continues to lose weight at approximately 1 to 2 pounds each month. His diabetes, sleep apnea, and hypercholesterolemia are resolved, and his blood pressure is controlled.