ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS OF PEDIATRIC ABUSIVE HEAD TRAUMA

Mechanism of Injury

Abusive head trauma encompasses many mechanisms of injury. Children who present with AHT may have been injured in a number of ways, including shaking, blunt impact, suffocation, strangulation, and others. It is important to remember that no single injury is diagnostic of AHT (Choudhary et al., 2018).

Each type of imposed stress produces a characteristic pattern of injury:

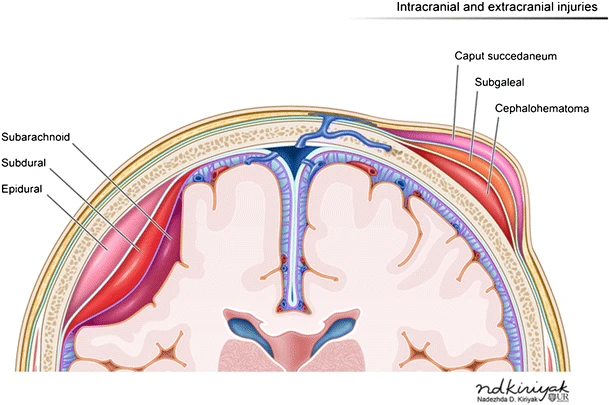

- Acceleration and deceleration through an arc (shaking) produce thin subdural hemorrhage and, commonly, retinal hemorrhages.

- Impact is associated with skull fractures, contra-coup bruising, and unilateral subdural hemorrhage.

- Strangulation causes hypoxia and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy.

These stresses may occur separately or in any combination.

When a baby is shaken, the neck snaps back and forth and the brain rotates, causing shearing stresses on the vessels and membranes between the brain and skull. (Source: Radiologyassistant.nl.)

Clinical Presentations

Healthcare professionals may first encounter young children with AHT in a range of clinical settings, including primary care, urgent care, and emergency departments. Since there are significant variations in the clinical presentation of children with AHT, it is important that professionals are trained to identify potentially life-threatening situations.

While there is an increased awareness now about AHT and how it may present, it is still important to realize that AHT may present with subtle signs and symptoms. A history of trauma is rarely provided in the initial stages, and if it is, it is usually reported as a fall from a distance less than 5 feet (APA, 2020).

Less severely injured infants and young children may present with symptoms that are quite nonspecific and without a history of trauma provided by a caregiver. These symptoms may be transient and improve if the trauma is not repeated. They include irritability, vomiting, and apnea. These and other symptoms of AHT are also seen in other minor medical conditions and can easily lead to a mistaken diagnosis of those conditions instead. Healthcare providers may have difficulty recognizing that such symptoms are the result of abuse, and the infant may return to an abusive environment (see also “Differential Diagnoses” below).

More seriously injured children have symptoms that should lead to rapid diagnosis of intracranial trauma. The caregiver may report a dramatic change in level of consciousness, as in acute collapse, such as unconsciousness, apnea, or seizures. An episode of minor trauma may be given as an explanation for the injury. Examples include falls off beds, being dropped by caregivers, or other minor contact injuries to the head.

Presenting History

Any reported history or statements made by the caregiver regarding the injury should be documented accurately and completely. It is best to include the specific questions asked as well as the responses. Information should be gathered in a nonaccusatory but detailed manner.

There are two general portions of the presenting history that are important to document. The first is the history of the injury event and the second is how the child responded or behaved after the injury.

Questions asked when taking a presenting history should include:

- What happened?

- Who was there when it happened?

- Where did it happen?

- When did it happen?

- What happened afterwards?

- When was the child noticed to be ill or injured? How did the child respond? When did symptoms start? How did you respond?

- What made you bring your child to the doctor (or hospital)?

- When was the last time your child was totally normal or well?

- What has your child been doing and how have they appeared during the last 24–48 hours?

Medical, Developmental, and Social History

Information that may be useful in the medical assessment of suspected physical abuse include:

- Past medical history (trauma, hospitalizations, congenital conditions, chronic illnesses)

- Nutrition history

- Seizure history

- Medications and immunizations

- Family history (especially of bleeding, bone disorders, and metabolic or genetic disorders, which often appear as a history of early deaths)

- Pregnancy history (wanted/unwanted, planned/unplanned, prenatal care, postnatal complications, postpartum depression, delivery in nonhospital settings)

- Familial patterns of discipline

- Child temperament (easy to care for versus fussy)

- History of past abuse to child, siblings, or parents, including history of Child Protective Services or police involvement

- Developmental history of child (language, gross motor, fine motor, psychosocial milestones)

- Substance abuse by any caregivers or people living in the home

- Social and financial stressors and resources (unemployment, divorce/separation, etc.)

- Violent interactions among other family members

(Christian, 2018)

The social history is a critical component of the evaluation. Asking parents about the household composition, other caregivers, siblings, substance abuse, mental illness, and social stressors can provide valuable information. It is preferable to interview caregivers separately; thorough and accurate documentation, including the use of quotes, is critical.

Explanations that are of concern for AHT include:

- Any infant or young child whose history is not plausible or consistent with the presenting signs and symptoms (i.e., explanation that is inconsistent with the pattern, age, or severity of the injury or injuries)

- History of behavior that is inconsistent with the child’s physical and/or developmental capabilities

- Presence of a new adult partner in the home

- History of delay in seeking medical attention

- History or suspicion of previous abuse

- Absence of a primary caregiver at the onset of injury or illness

- Physical evidence of multiple injuries at varying stages of healing

- Unexplained changes in neurologic status, unexplained shock, and/or cardiovascular collapse

(CDC, 2018)

Physical Assessment

There are various signs and symptoms of AHT that can be recognized in a physical assessment of the child. Depending on the severity of the clinical presentation, initial assessment is often focused on identifying and treating life-threatening issues. This initial assessment focuses on the airway, breathing, circulation, and neurologic status.

As noted above, the consequences of less severe cases may not be brought to the attention of healthcare professionals and may never be diagnosed. In the most severe cases, which usually result in death or severe neurological consequences, the child usually becomes immediately unconscious and suffers rapidly escalating, life-threatening central nervous system dysfunction.

Common presenting signs and symptoms of AHT are:

- Lethargy/decreased muscle tone

- Extreme irritability

- Decreased appetite, poor feeding, or vomiting for no apparent reason

- Grab-type bruises on arms or chest (rare)

- No smiling or vocalization

- Poor sucking or swallowing

- Rigidity or posturing

- Difficulty breathing

- Seizures

- Head or forehead appears larger than usual (disproportional growth may be demonstrated on a growth chart if data are available) or soft-spot on head appears to be bulging

- Inability to lift head in an age-appropriate manner

- Inability of eyes to focus or track movement or unequal size of pupils

(NCSBS, 2018)

Complete physical exam for any young child with suspected AHT includes:

- Inspection of all body parts, scalp, ears, and hair

- Inspection of the mouth (lip, tongue, buccal) to look for frenula tears or dental injuries

- Palpation of legs, arms, hands, feet, and ribs to feel for crepitus or deformities

Nursing neurologic assessment of the child with head trauma includes evaluation of:

- Eye opening

- Arousability level or irritability/consolability

- Symmetry of facial expressions

- Movement of upper and lower extremities

- Increased weakness or pitch in cry/vocalizations

- Fontanels

- Each pupil separately for size, shape, equality of reaction to light

- Ability to track objects

- Muscle tone for rigid extension or flexion of extremities, flaccidity, and/or unusual posturing

Research has identified several specific types of injuries as being associated with AHT. These include retinal hemorrhage in 85%, subdural hematoma in over 70%, and hypoxic-ischemic injury and cerebral edema as significantly associated with AHT (O’Meara et al., 2020).

RETINAL HEMORRHAGE (RH)

Retinal hemorrhage is bleeding in the back wall of the eye. Retinal hemorrhages are a common but not universal finding in AHT. Clinical and pathological studies have shown strong associations of severe RH and AHT, especially in infants. It is important to understand, however, that RHs can result from other causes, including medical disease (coagulopathy or leukemia) or accidental or birth trauma.

Retinal hemorrhages can vary in size, number, and location within the retina itself. An examination by using indirect ophthalmoscopy is required in the evaluation of AHT, preferably by an ophthalmologist with pediatric or retinal experience. Distinguishing the number, type, location, and pattern of RHs is important in evaluating a differential diagnosis. Hemorrhages that extend to the ora serrata and involve multiple layers of the retina are strongly associated with AHT. Because some RHs can be transient, it is important to conduct the eye exam as soon as possible if AHT is suspected (Christian, 2015; Christian & Levin 2018).

SUBDURAL HEMATOMA (SDH)

Subdural hematoma is bleeding inside the skull but outside the brain. SDH is found in the majority (up to 90%) of victims of pediatric AHT. Although SDH is not exclusive to abusive trauma, a number of studies have demonstrated a significant and strong association of SDH with abuse compared with accidental injury. This is because inflicted injuries with or without impact can lead to tearing of cerebral convexity bridging veins at the junction of the bridging vein and superior sagittal sinus, and also because rupture of the arachnoid membrane allows cerebrospinal fluid to enter the subdural space (Choudhary et al., 2018).

A subarachnoid hemorrhage can be seen in the subarachnoid space between the dura mater and pia mater layers of the meninges. (Source: ND Kiriyak, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.)

FRACTURES

The possibility of concurrent fractures in other parts of the body is important to consider in children presenting with possible AHT. A multi-center study found fractures in 32% of AHT cases. The skull (43%) and ribs (48%) were affected most frequently, but only 8% of the cases showed classic metaphyseal lesions. In 48% of the cases, healing fractures were present (Feld et al., 2021).

Understanding the unique physiology of children’s skeletal injuries is crucial for correctly differentiating between injuries incurred from normal childhood trauma and those from abusive trauma in general. Fractures in children can be divided into the following three categories based on the relative likelihood of accidental vs. abusive origin:

- Highly specific injuries include metaphyseal fractures (such as classic metaphyseal lesions [CMLs]), rib fractures (especially posterior), skull fractures, scapular fractures, sternal fractures, and outer-third clavicular fractures.

- Moderate-specificity fractures include multiple fractures (especially if bilateral), fractures of different ages, epiphyseal separations, vertebral body fractures, digital fractures, spinal humeral fractures, and complex skull fractures.

- Common but low-specificity fractures include middle clavicle fractures, long-bone shaft fractures, and linear skull fractures.

(Knipe, 2020)

Moderate- and low-specificity fractures become highly specific when a credible history of accidental trauma is absent, particularly in infants.

SKIN LESIONS AND BRUISING

Bruising is the most common injury from physical abuse, and also the most common injury to be overlooked or misdiagnosed before an abuse-related fatality, and/or resulting in an error in medical decision making that leads directly to poor patient outcomes. A multicenter study found skin lesions (hematomas and abrasions) in 53% of AHT cases, with the face (76%), scalp (26%), and trunk (50%) being the major sites. In 48% of cases, healing skin lesions were observed. Nearly 80% of the cases with fractures also showed skin lesions (Feld et al., 2021).

The mnemonic TEN-4-FACESp was developed as a bruising clinical decision rule for distinguishing abusive from nonabusive trauma in children based on the characteristics of their bruising. Any bruising on a child age 4.99 months or younger is considered an affirmative finding. Likewise, an affirmative finding in children age 4.99 years or younger for any one of the following three components indicates a potential risk for abuse and warrants further evaluation by the medical team:

- Is there bruising on the TEN (torso, ears, or neck) region?

- Is there bruising or injury involving the FACES region (frenulum, angle of jaw, cheeks, eyelids, subconjunctivae)?

- Is the bruising patterned (P)?

(Pierce et al., 2021)

ORAL INJURIES

The mouth should be fully examined and any missing or abnormal teeth recorded. It is also very important to be aware of normal dentition in a child and to be alert to subtle changes (e.g., the most common oral injuries described are bruising or lacerations to the lips). Other possible oral injuries include unexplained bruising to the cheeks, ears, neck, or trunk in association with a torn frenum. A torn frenum may occur with force-feeding an infant.

SPINAL INJURIES

Evaluating for spinal injuries is a common practice in the diagnosis of AHT and is seen as both clinically and forensically valuable. Spinal injury has been associated with more severe injury, and spinal subdural hemorrhage might support a mechanism of severe acceleration/deceleration head injury and a diagnosis of AHT (Rabbitt et al., 2020).

ABDOMINAL INJURIES

Liver lacerations and other abdominal organ injuries are often seen in AHT cases but are commonly missed because the internal injuries are not visible to the naked eye. Blood tests (liver transaminase levels, pancreatic amylase and lipase) can immediately alert clinicians to the possibility of an occult abdominal injury (Lindberg et al., 2015; Kempe Center, 2015).

Diagnostic Procedures

All infants and children with suspected AHT require cranial CT, MRI, or both.

CT SCAN

A CT scan is usually the first modality of choice diagnostically in symptomatic children due to its availability, rapidity, and ability to look at brain parenchyma, vascular structures, bone, and scalp. The CT in AHT, usually performed without contrast media, may demonstrate intracranial bleeding, both parenchymal or extra-axial (between the brain and skull). A CT of the head will identify abnormalities that require immediate surgical intervention and is preferred over MRI for identifying acute hemorrhage and skull fractures and scalp swelling from blunt injury. Three-dimensional (3D) image reconstruction is better than plain films in identifying and delineating skull fracture.

Abdominal CT scan is the most sensitive imaging mode and is recommended when abdominal injury is suspected.

MRI

MRI is the optimal modality for assessing intracranial injury, including cerebral hypoxia and ischemia, and is used for all children with abnormal CT scans, asymptomatic infants with noncranial abusive injuries, and for follow-up of identified trauma (Christian, 2015). There is increasing data to support MRI of the spine since spine MRI can identify ligamentous changes, spinal subdural hemorrhage, and other diagnostic evidence of abusive head trauma. Full spine is recommended rather than c-spine alone because of the tendency of subdural blood to track down (Rabbitt et al., 2020).

SKELETAL SURVEY

Skeletal surveys are recommended as the “universal screening/examination” in cases of known or suspected physical abuse and in serious head trauma in children younger than 2 years of age because they can help detect otherwise occult trauma to the bones. Skeletal surveys are conducted per the American College of Radiology parameters. Full-body “baby grams” (radiographs that include the whole body or the chest and abdomen on a single image) should be avoided in place of a skeletal survey since they are not sufficient to rule out fractures (ACR, 2021). Images are reviewed by someone with adequate expertise in the field (i.e., pediatric radiologist). If an adequate study cannot be readily obtained, transferring or referring a patient to a pediatric center with expertise in performing and reading skeletal surveys should be strongly considered.

The diagnosis of abuse may be made or supported if unsuspected or occult traumatic injuries are found in other parts of the body. Such accompanying skeletal fractures are seen in roughly half of the cases of abusive head injury. Rib fractures may be the only abnormality in about 30% of the children. A repeat limited skeletal survey after two weeks can detect additional fractures and can provide fracture dating information (Christian, 2015; Wootten-Gorges et al., 2017).

While bony injuries are rarely life threatening, they can provide important evidence for the diagnosis of physical abuse. Skeletal surveys can help to identify characteristic injury patterns such as the classic metaphyseal lesion in long bones, sometimes referred to as “bucket-handle” and “corner” fractures according to their appearance, or posterior rib fractures, both of which are rarely accidental and thus strongly suggestive of abuse even when clinical information is lacking (Jain, 2015).

Per the American College of Radiology parameters, skeletal surveys in cases of known or suspected child abuse should include all elements described in the table below.

| (ACR, 2016) | |

| Appendicular skeleton |

|

| Axial skeleton |

|

LAB TESTING

The standard workup for AHT (or any physical abuse) includes:

- CBC (complete blood count)

- Coagulation panel

- CMP (comprehensive metabolic panel)

- Lipase

- Urinalysis

- Von Willebrand’s panel or antigen (depending on availability)

- If any fractures are present:

- Calcium

- Phosphorous

- Alkaline phosphatase

- Parathyroid hormone (PTH)

- Vitamin D 25-hydroxy

NEUROLOGIC ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Pediatric neurologic assessment tools include a variety of scales healthcare professionals can use to assess and monitor level of consciousness in young children. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) continues to be one of the most widely used to evaluate injury severity of young children presenting with altered level of consciousness. Any combined score of less than 8 suggests severe brain injury and represents a significant risk of mortality (see table below).

| Behavior | Response | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Source: Brainline.org, n.d. | ||

| Eye opening | Does not open eyes | 1 |

| Opens eyes in response to painful stimuli | 2 | |

| Opens eyes in response to speech | 3 | |

| Opens eyes spontaneously | 4 | |

| Verbal response | No verbal response | 1 |

| Inconsolable, agitate | 2 | |

| Inconsistently inconsolable, moaning | 3 | |

| Cries but consolable, inappropriate interactions | 4 | |

| Smiles, orients to sounds, follow objects, interacts | 5 | |

| Motor response | No motor response | 1 |

| Extension to pain (decerebrate response) | 2 | |

| Abnormal flexion to pain for an infant (decorticate response) | 3 | |

| Infant withdraws from pain | 4 | |

| Infant withdraws from touch | 5 | |

| Infant moves spontaneously or purposefully | 6 | |

| Total score | Best response | 15 |

| Comatose client | 8 or less | |

| Totally unresponsive | 3 | |

SCREENING TOOLS

There are few clinical decision rules in the child protection field, and the evidence is weak for the diagnostic value of screening tools based on physical examination of children without previous suspicion of child maltreatment (Cowley et al., 2015). However, some research tools have been developed that show high prediction for AHT. While none are aimed to diagnose AHT, they may prompt clinicians to seek further clinical, social, or forensic information (Pfeiffer et al., 2018). Three examples include:

PediBIRN

Hymel and colleagues (2014) derived the PediBIRN four-variable clinical rule for predicting AHT. The objective of this tool is to detect AHT among acutely head-injured children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. The four variables include:

- Any clinically significant respiratory compromise before admission

- Bruising of the torso, ears, or neck

- Bilateral or interhemispheric subdural hemorrhages or collections

- Any skull fractures other than an isolated, unilateral, nondiastatic, linear, or parietal fracture

PIBIS

The PIBIS (Pittsburg Infant Brain Injury Score) assists in determining which high-risk infants in the emergency department should undergo CT to rule out abnormalities, including AHT. This tool has the objective of detection of abnormal neuroimaging in well-appearing children with nonspecific symptoms. The scoring includes four criteria, and a child with a score of 2 or more points should undergo neuroimaging to check for abnormal findings. Criteria include:

- Abnormality on dermatological examination (2 points)

- Age at or above 3.0 months (1 point)

- Head circumference over 85th percentile (1 point)

- Hemoglobin below 11.2 g/dl (1 point)

(Berger et al., 2016)

PredAHT

Predicting Abusive Head Trauma (PredAHT) was developed to help healthcare providers differentiate accidental head trauma from AHT. This tool estimates the probability of AHT in young children presenting with intracranial injuries and specific combinations of six features:

- Head or neck bruising

- Seizures

- Apnea

- Rib fracture

- Long-bone fracture

- Retinal hemorrhage

The estimated probability of AHT varies from 4% when none of the features are present, to >81.5% when three or more of these six features are present, to nearly 100% when all six features are present (Pfeiffer et al., 2018; Cowley et al., 2015).

Distinguishing between Accidental and Abusive Head Trauma

There are several challenges to differentiating between accidental (nonabusive/noninflicted) trauma or age-appropriate injuries and child abuse in infants and young children. This is especially true in children who are not yet verbal enough to explain what happened to them (i.e., infants, toddlers, and children with developmental delay and/or altered levels of consciousness).

Because of this, knowledge of typical developmental patterns of injury is helpful. That is, how does the presenting pattern(s) of injury and the child’s age and developmental level match up with the reported mechanism of injury?

DEVELOPMENTAL PATTERNS OF INJURY

Developmental patterns of injury seen in the 0- to 3-year-old range (the age range most frequently seen with AHT) include:

- Trauma from falls from furniture, down stairs, or being dropped by another person

- Traumatic delivery (e.g., forceps, vacuum extraction, and/or breech)

- Motor vehicle accidents

Head injury is frequently involved with these traumas because of several factors, including the larger head-to-body ratio and the inability to shield oneself during a fall.

Developmentally, this age range is at risk for accidental injury because the child’s developmental milestones include increasing motor skills and curiosity, allowing them a greater range and access to potential hazards. The advancing physical abilities of young children often precede their ability to understand the consequences of their actions. Thus, parent/caregiver knowledge of growth and developmental milestones may reduce the likelihood that they will misjudge the ability of the child and utilize an inappropriate supervision strategy. The mechanisms seen in accidental (noninflicted) injuries are generally different in these types of injuries as compared to AHT, as discussed below.

ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS

Because this situation is highly charged for both the family and all the healthcare providers involved, it is a good idea to have a mental checklist in place to both pose questions and evaluate responses in relation to the specific patient in question. Providers should further objectively and clearly document the history as described by the parents and/or caregivers present.

The following are questions a clinician can ask oneself to help separate the unintentional from the inflicted injury:

- What is the age of the child?

- What are the normal behaviors of a child at that age? Developmental stages of childhood determine what kinds of injuries are likely to be seen. The motor skills of the child determine what the child could have done to incur injury.

- Based on the child’s age, is the presenting injury plausible?

- Is the history plausible? Could this injury have been sustained in the manner described? Does the history change with changing information supplied to the caretaker? Adjustments in the account of the injury may be made by caretakers to fit the evolving information, indicating the tailoring of the history to fit new information. Does the history change when related in subsequent accounts by other family members?

- Was the injury witnessed? The lack of information as to how a serious injury has occurred should raise the index of suspicion for an abusive origin.

- Is the social situation in which the injury occurred a high-risk environment? The presence of community or intrafamilial violence, substance abuse, chaotic living arrangements, poverty, social isolation, transient lifestyles, mental health issues, or conflict among family members are red flags.

- Can the described mechanism of injury account for the observed injury? What else could produce the clinical picture?

- Can the history be independently verified (through photographs, scene investigation, etc.)?

Explanations that are concerning for intentional trauma include:

- No explanation or vague explanation for a significant injury

- An important detail of the explanation that changes dramatically

- An explanation that is inconsistent with the pattern, age, or severity of the injury or injuries

- An explanation that is inconsistent with the child’s physical and/or developmental capabilities

- Different witnesses who provide markedly different explanations for the injury or injuries

(Christian, 2015)

WHAT TO DO WHEN CONSIDERING A DIAGNOSIS OF AHT

- Call law enforcement directly from the point of care if there are any immediate concerns for the child’s safety.

- Call social services. They can assist in interviewing family members and discussion with CPS.

- Call Child Protective Services. They will take a report and decide whether to pursue an investigation. Often, CPS is involved in assisting with the disposition of the child if not admitted (they will make a safety plan) or when child goes home from the hospital. CPS may also contact law enforcement.

- Call a child abuse consultant. These professionals are key in suggesting studies for workup as well as discussing appropriate disposition. Regional child abuse centers often have a consultant on call if there is not one available in one’s own system.

- General guidelines for discharge. If there is any question about the child’s injury or safety at home (e.g., unexplained injury) and/or further workup is required (e.g., skeletal survey), the child should be admitted to the hospital for observation and protection until the workup can be completed and a safe disposition decision can be made between admitting provider, child abuse consultant, social services, and CPS.

(See also “Reporting Child Abuse and Neglect” below for information on when a healthcare provider may be mandated to report suspected AHT.)

CASE

Anthony is an 11-month-old admitted to the ED with a history of altered level of consciousness and multiple facial, skull, and body soft tissue injuries after a reported “fall down the stairs while in a baby walker.” This occurred while he was at a family childcare home. He regained consciousness but was very irritable.

On arrival to the ED, the triage nurse assessed his airway, breathing, circulation, and level of consciousness. He received a prompt evaluation by the ED physician for head trauma because of the history. In this case, the details of the event and injury patterns seemed to match up. Anthony had a CT of the head and ophthalmologic evaluation, and both were found to be negative.

Anthony was discharged home from the ED after observation. The family childcare home was cited for a health and safety violation.

Differential Diagnoses

It is also important to rule out underlying conditions that may cause some of the same signs or symptoms associated with AHT or other abuse. Where indicated, medical professionals should inquire about the presence of any of the following conditions or practices:

- Congenital, metabolic, or neoplastic conditions (e.g., aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, brain tumor, leukemia)

- Connective tissue disease or osteogenesis imperfecta, which may lead to fragile bones that fracture with less force than would be expected

- Acquired causes (e.g., meningitis, obstructive hydrocephalus)

- Undetected bleeding disorders that can lead to abnormal bleeding patterns (e.g., hemophilia, Von Willebrand’s disease, liver disease)

- Traditional or alternative healing practices, which may lead to unusual bruising and scarring patterns (e.g., coin rubbing, cupping, or burning herbs on the skin over acupuncture points)

(Killion, 2017)