ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The cardinal symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease include:

- Memory impairment

- Executive function and judgment/problem-solving impairment

- Behavioral and psychological symptoms

Memory Impairment

Early in the course of Alzheimer’s, individuals are usually aware of their memory deficit and may make notes to remember important things. Sooner or later the memory deficit is such that they may forget to check their notes. Later they may become frightened and apprehensive about their memory problems, causing them to feel depressed and discouraged. As the disease progresses, individuals lose insight into their memory deficit and are no longer aware of it. It is at this point that they require protection to remain safe.

The following are early signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease memory impairment compared to typical age-related changes.

| Memory Impairment with Alzheimer’s | Typical Age‑Related Memory Changes |

|---|---|

| (Alzheimer’s Association, 2021c) | |

|

Memory loss that disrupts daily life:

|

Sometimes forgetting names or appointments but remembering them later |

|

Challenges in planning or solving problems:

|

Making occasional errors when managing finances or household bills |

|

Difficulty completing familiar tasks, such as:

|

Occasionally needing help to use a piece of household equipment (e.g., microwave setting) or other technical or mechanical device |

|

Confusion about time and place:

|

Getting confused about the day of the week but figuring it out later |

|

Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships:

|

Vision changes related to cataracts or other age-related changes or diseases |

|

New problems with words in speaking or writing:

|

Sometimes having trouble finding the right word |

|

Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps:

|

Misplacing things from time to time and retracing steps to find them |

|

Decreased or poor judgment:

|

Making a bad decision or mistake once in a while (e.g., neglecting to change the oil in the car) |

|

Withdrawal from work or social activities:

|

Sometimes feeling uninterested in family or social obligations |

|

Changes in mood and personality:

|

Developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted |

HOW MEMORIES ARE MADE

Memory formation is a cognitive process that involves:

- Receiving: A piece of information is received through the five senses.

- Encoding: The information received is converted into a form that can be stored and held in the short-term memory first. The incorporated memory stays there for just 30 seconds unless it is repeated over and over again in the mind (rehearsed).

- Consolidation/storing: Information from the short-term memory is transferred into long-term memory storage.

- Retrieving: The information stored in the long-term memory is recalled.

(Alzheimer’s Society, 2021b)

TYPES OF MEMORY AND ASSOCIATED AD SYMPTOMS

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease marked by deficits in episodic memory, working memory (WM), and executive function.

Memory is a large part of a person’s identity, and there are different types. Each type uses a different network in the brain, and therefore, one type can be affected by disease or injury while another type functions normally. Memory systems are divided into two broad categories:

- Declarative memory has a conscious component and includes memories of facts and events (i.e., “knowing what”).

- Nondeclarative memory does not have a conscious component. It includes memories for skills and habits, simple forms of associative learning, and simple forms of nonassociative learning such as habituation and sensitization (i.e., “knowing how”).

(The Human Memory, 2020)

Episodic Memory

Episodic memory is declarative and includes information about recent or past events and experiences, such as where a person parked their car this morning or the dinner a person had with a friend a month ago. These memories often include recalling emotions or feelings. Experiences that cause strong positive or negative feelings are easier to recall many years later. Memory of events that occurred in the distant past is referred to as long-term or remote memory. Because remote memories eventually become independent of the hippocampus and are stored in the neocortex, they are not as severely disrupted in AD (The Human Memory, 2020; UCSF, 2021a).

This explains why individuals with AD eventually “live in the past,” such as wanting to milk the cows even though they haven’t lived on a farm for over 20 years, wanting to go to work even though they retired 30 years ago, etc. It also explains why they’re able to remember events many decades old but unable to remember what happened that morning.

Semantic Memory

Like episodic memory, semantic memory is declarative and refers to a portion of long-term memory that stores information about facts one knows about the world and language that is common knowledge, such as the meaning of words, names of colors, etc. It is also used to remember familiar faces or objects. Problems with semantic memory can include:

- Anomia, or the inability to find the right word. At first the person with Alzheimer’s is aware of this and may make up for it by using sentences to describe an object they cannot name. As the condition worsens, anomia comes to include common objects such as an eating utensil or a pen.

- Aphasia, or difficulty with and eventual loss of the ability to speak or understand spoken, written, or sign language. In the advanced stage of the disease, speech becomes unintelligible, and eventually the person becomes mute.

- Agnosia, or loss of the ability to recognize what objects are and what they are used for. This may involve failing to recognize who people are. Agnosia can be visual, auditory, or tactile, but visual is the most common form.

(Blanchard, 2021)

Procedural Memory

Procedural memory is a form of nondeclarative memory that includes how to carry out actions both physically and mentally, including actions that have become automatic. The loss of procedural memory can result in difficulties carrying out routine activities such as dressing, bathing, and cooking.

Apraxia is one of the most common deficits in procedural memory observed in patients with Alzheimer’s. It is a disorder of “how” and “when” to correctly perform meaningful and purposeful actions. A person with apraxia is unable to put together the correct muscle movements, which can also lead to problems with speech, such as:

- Distorted, repeated, or left-out speech sounds or words

- Inability to put words together in a correct order

- Struggling to pronounce the right word

- More difficulty using longer words

- Better writing ability than speaking ability

Other forms of apraxia include:

- Buccofacial or orofacial apraxia: inability to carry out movements of the face on demand

- Ideational apraxia: inability to carry out learned complex tasks in the proper order (e.g., putting on socks before putting on shoes

- Ideomotor apraxia: inability to voluntarily perform a learned task when given the necessary objects to do so

- Limb-kinetic apraxia: difficulty making precise movements with an arm or leg (e.g., buttoning a shirt or tying a shoe)

- Gait apraxia: inability to take even a small step

(Libon et al, 2020; NIH, 2021d)

Visuospatial Memory

Visuospatial memory gives one the ability to navigate in the environment and to identify, integrate, and analyze space and visual form, details, structure, and spatial relations in several dimensions. It requires the formation, storing, and retrieval of mental maps. In persons with Alzheimer’s, loss of this ability results in getting lost in familiar surroundings, wandering, and losing the ability to live independently (Kim & Lee, 2021).

Working Memory

Working memory, often referred to as short-term memory, is the capacity to temporarily store information in a flexible state so that it can be manipulated in order to complete goal-oriented behaviors (e.g., remembering the numbers when adding in one’s head). Working memory dysfunction is possible in the later phases of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s (Center for Cognitive Health, 2020).

Executive Function, Judgment, and Problem-Solving Impairment in AD

Executive functioning refers to high-level cognitive skills required for control and coordination of other cognitive abilities and behaviors. Executive functions can be divided into organizational and regulatory abilities.

Organizational abilities are techniques used by individuals to facilitate the efficiency of future-oriented learning, problem-solving, and task completion. Organization requires the integration of several elements to reach a planned goal. These include:

- Attention: the capacity to be paying attention to a situation or task in spite of distractions, fatigue or boredom

- Planning: the ability to create a mental roadmap to reach a goal or to complete a task

- Sequencing: the ability to perceive and execute a set of actions that follow a particular order

- Problem-solving: the capacity to identify and describe a problem, and generate solutions to fix it

- Working memory: the ability to hold information in mind while performing complex tasks

- Cognitive flexibility: the ability to revise plans in the face of obstacles, setbacks, new information, or mistakes

- Abstract thinking: the ability to think about objects, principles, and ideas that are not physically present

- Rule acquisition: how individuals acquire skill in applying problem-solving rules

- Selecting relevant sensory information: how an individual analyzes incoming sensory information in order to form visually guided motor decisions

Regulatory abilities involve evaluating available information and modulating a response to the environment. These include:

- Initiation of action: the ability to begin a task in a timely fashion

- Self-control: the ability to manage emotions in order to achieve goals, complete tasks, or control and direct behavior

- Emotional regulation: the ability to keep one’s emotions under control

- Monitoring of internal and external stimuli: the ability to monitor and change behavior as needed, plan future behavior when faced with new situations and anticipate outcomes to changing situations

- Initiating and inhibiting context-specific behavior: the ability to inhibit or control impulsive (or automatic) responses, and create responses by using attention and reasoning

- Moral reasoning: the logical process of determining whether an action is right or wrong

- Decision-making: the ability to be proficient in making choices between two or more alternatives

(UCSF, 2021b)

Early in Alzheimer’s, impairment of executive function can range from subtle to prominent. Family and coworkers may notice that the person is less organized or less motivated, and multitasking is often impaired. In addition, the person develops poor insight and reduced ability for abstract reasoning. As Alzheimer’s progresses, the person becomes unable to complete tasks.

The patient with Alzheimer’s often has anosognosia, which is a reduced insight into one’s neurological deficits. Many patients underestimate their deficits or try to offer explanations or alibis for them when they are pointed out by others. It is often a family member and not the patient who brings cognitive impairment to the attention of healthcare professionals. Lack of insight can present problems with safety, as patients may try to do tasks they are no longer able to perform, such as driving (Wolk & Dickerson, 2020).

Psychological and Behavioral Symptoms in AD

Psychological and behavioral symptoms are common in Alzheimer’s disease, in particular during the middle and late stages of the illness. Psychological and behavioral symptoms affect up to 90% of patients diagnosed with dementia during the course of their illness. Patients with psychological and behavioral symptoms experience emotional distress, diminished quality of life, greater functional impairment, more frequent hospitalizations, increased risk of abuse and neglect, and decreased survival. Caregivers experience increased burden of stress and depression.

Some common psychological and behavioral changes are described in the table below:

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| (UCSF, 2021c) | |

| Apathy and indifference |

|

| Depression and dysphoria |

|

| Euphoria and elation |

|

| Anxiety |

|

| Irritability and lability |

|

| Inappropriate behaviors |

|

| Eating disorders |

|

| Sleep disturbances |

|

| Repetitive motor behaviors |

|

| Psychosis (during late-stage AD) |

|

Clinical Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Signs and Symptoms

Patients with Alzheimer’s disease go through different stages as the disease progresses and exhibit different signs and symptoms during each stage. The rate of progression of Alzheimer’s disease varies widely. On average, people with Alzheimer’s live between 3 and 11 years after diagnosis, but some survive 20 years or more.

Alzheimer’s disease has been classified into either three, four, five, or seven stages used for determining the level of care the person requires and for comparing groups of such patients with one another. These classifications are somewhat arbitrary, and there is a great deal of overlap among the various stages. One of the most commonly used classifications divides the disease process into five stages.

STAGE 1: PRECLINICAL ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Alzheimer’s disease begins long before any symptoms become apparent. This stage is called preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. During this stage of the disease there are no noticeable symptoms either to the person with the disease or those around them. This stage can last for years, and even decades, before symptoms begin to appear and a diagnosis is made.

STAGE 2: MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

During this stage, minor changes in memory and thinking ability develop that are not significant enough to affect work or relationships. The person may have memory lapses when dealing with information that is usually easily remembered, such as conversations, recent events, or appointments. The person in this stage may also have trouble judging time required for completing a task and judging correctly the number of sequences of steps needed to complete a task. Making good decisions may become harder for people during this stage.

Other problems during this stage may include:

- Problems remembering names

- Forgetting material that was just read

- Experiencing increased trouble with planning or organizing

STAGE 3: MILD DEMENTIA DUE TO ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Alzheimer’s disease is often diagnosed in this stage when it is clear to family and healthcare professionals that a person is having significant problems with memory and thinking that impact daily functioning. During this stage, the person may experience:

- Memory loss for recent events

- Difficulty with problem-solving, complex tasks, and sound judgment

- Changes in personality

- Difficulty organizing and expressing thoughts

- Misplacing belongings

- Getting lost

STAGE 4: MODERATE DEMENTIA DUE TO ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

During this stage, which lasts from 2 to 10 years and is the longest stage, the person becomes more confused and forgetful and begins to require some assistance with daily activities and self-care. The person may experience:

- Increasing trouble planning complicated activities (e.g., preparing a dinner)

- Trouble remembering events remote as well as recent memories

- Problems learning new things

- Trouble remembering their own name

- Being unable to recall information about themselves, such as their address or phone number

- Problems with reading, writing, and working with numbers

As the disease progresses, the person may:

- Know that some people are familiar but cannot remember their names

- Forget the names of a spouse or child

- Lose track of time and place

- Need help with daily self-care activities

- Become moody or withdrawn

- Have personality changes

- Be restless, agitated, anxious, or tearful, especially in late afternoon or at night

- Become aggressive

- Experience sleep problems

- Wander away from home

- Develop psychotic symptoms including hallucinations and delusions

- Lose impulse control

- Begin to lose bladder and bowel control

STAGE 5: SEVERE DEMENTIA DUE TO ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

During this stage of the disease mental functioning continues to decline, and the person loses the ability to communicate coherently. Severe impairment of all cognitive functions occurs, and at this point the person requires total assistance with personal care. As the disease continues to progress the person may remain in bed most or all of the time as the body begins to shut down, and the following may occur:

- Loses many physical abilities, including walking, sitting, and eating

- Able to say some words or phrases, but unable to have a conversation

- Becomes unaware of recent experiences and surroundings

- Needs help with all activities all of the time

- Becomes unable to recognize immediate family members

- Loses weight

- Experiences seizures

- Experiences skin infections

- Groans, moans, or grunts

- Sleeps an increased amount

- Loses bladder and bowel control

- Has impaired swallowing (which can lead to aspiration pneumonia, the most common cause of death in persons with Alzheimer’s disease)

(Mayo Clinic, 2021b; Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2021a)

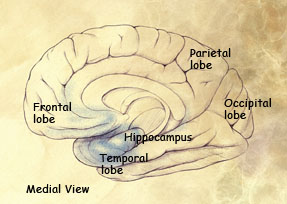

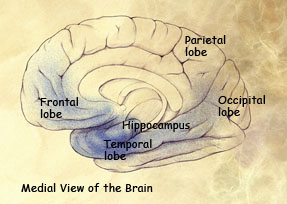

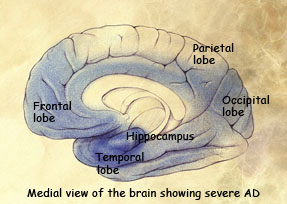

AREAS OF THE BRAIN AFFECTED DURING THE STAGES OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Preclinical stage: Areas of early damage to the hippocampus and portions of the frontal lobe (in blue)

Mild to moderate stages: Spread of damage forward into the frontal lobe and backward into the temporal lobe.

Severe stage: Extensive damage to areas during the final stage of Alzheimer’s disease.

(Source: National Institute on Aging.)