DISEASE-SPECIFIC DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT, AND PREVENTION

Most STIs are a threat to both the health of the patient and the health of the community, and treatment is always recommended. STIs present with a variety of syndromes, but their treatment depends on the specific agent causing the problems.

The following are the current recommended treatments for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HPV, the STIs recognized by the National Strategic Plan as reaching epidemic proportions. The drugs and administration regimens offered here are examples of current recommendations based on CDC guidelines, but actual treatments must be tailored to the specific patient.

(For a link to the most current CDC treatment recommendations, see “Resources” at the end of this course.)

TWO TREATMENT PRINCIPLES

1. Treat As Soon As Possible

Early care for STIs can shorten the time for screening, diagnosing, treating, and educating. Early treatment is based on the patient’s symptoms, the STI risk assessment from the medical history, and the signs observed during the physical examination. Rapid laboratory test results may be available for use in diagnosis, but when tests take a day or more to produce results, presumptive treatment is often started before a diagnosis has been verified. When available, medications are given in single-dose regimens that are dispensed during the initial visit, and the patient is asked to take the medicine immediately.

The aggressive treatment of STIs may seem at odds with slowing the development of antibiotic-resistant microbes. The quick treatment of STIs, however, is driven by public health concerns. When patients seek care, a follow-up visit for treatment cannot be guaranteed. Sometimes, the best assurance that diseases will not be spread further is treatment at the first visit.

2. Extend Treatments Beyond the Individual Patient

The patient is instructed to avoid sexual contact for the appropriate period of time depending on the infection and the treatment regimen. The patient is also advised to avoid sexual contact with partners until the partners have also been treated. The patient is instructed to notify recent sexual partners about the patient’s STI, and the partners are encouraged to have STI testing. The patient is assured that the confidentiality of all parties’ medical records will be strictly preserved.

(Mayo Clinic, 2021a)

Chlamydial Infections

Of the reportable diseases, chlamydial infections were the most common STDs/STIs in the United States in 2019. Chlamydial infections were more prevalent among young women, with 3,728.1 cases per 100,000, an increase of 10% from 2015. The rates among males increased 32.1% from 2015 to 2019, possibly a result of increased availability of urine testing and extragenital screening and increased transmission in males. Both genders show a decrease in the occurrence of chlamydia as age increases. However, many cases go undiagnosed because most people with chlamydia are asymptomatic and do not seek testing. Chlamydia can be prevented by using male latex condoms, abstinence, and monogamy (Workowski et al., 2021; CDC, 2021e).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Chlamydial infections produce genital or lower urinary tract infections. After a person acquires a chlamydial infection, there is an incubation period of several weeks before the organism produces symptoms. But chlamydial infections are frequently asymptomatic; only 10% of men and 5%–30% of women with laboratory-confirmed chlamydial infection develop symptoms, potentially causing reinfection of sexual partners (CDC, 2021e).

In men, symptomatic chlamydial infections show up as urethritis or epididymitis, with pain and swelling around a testicle. Chlamydial urethritis produces a mucoid, mucopurulent, or purulent discharge; inflammation; pain on urination; and urethral itching.

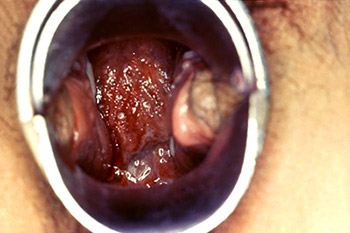

In women, symptomatic chlamydial infections show up most often as cervicitis. Chlamydial cervicitis produces a mucopurulent or purulent discharge in the endocervical canal; pain on urination or during intercourse; and vaginal bleeding after intercourse or between periods. Alternately, chlamydial cervicitis sometimes gives no other findings than a friable cervix on speculum examination.

Untreated, chlamydial cervicitis can spread and cause PID, which can then lead to infertility or ectopic pregnancies; and women may eventually develop lower abdominal pain, lower back pain, nausea and vomiting, fever, painful sex, and breakthrough bleeding during the menstrual cycle. During vaginal births, pregnant women can pass chlamydial infections to their newborns. The resulting infection can cause pneumonia and conjunctivitis in the infant (CDC, 2021e).

Colposcopic view of a female patient’s cervix with signs of erosion and erythema due to a Chlamydia trachomatis infection. (Source: CDC/Dr. Lourdes Fraw, Jim Pledger, Public Health Image Library.)

SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS OF CHLAMYDIA

The CDC recommends annual chlamydia screening for all sexually active females younger than 25 and for women 25 years and older with risk factors such as a new sex partner or multiple partners. Pregnant women should be screened during their first prenatal care visit (CDC, 2021f). For women, screening for asymptomatic cases is important because routine screening has been shown to reduce the number of cases of PID.

To make widespread screening practical, urine specimens and self-obtained vaginal swabs can be used because they provide effective samples for chlamydia screening tests, although examinations by a licensed provider are optimal. Urine samples are the test of choice for diagnosing chlamydia in men.

Diagnostic tests include urine sample, nucleic acid amplification, culture, and serology. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are the most sensitive and can be performed on vaginal or urine specimens (CDC, 2021e).

Women diagnosed with chlamydial infection should be retested approximately three months after treatment (CDC, 2021e). Cultures can be used to diagnose rectal and pharyngeal chlamydia. Chlamydia cultures are also often combined with Pap smears.

TREATMENT OF CHLAMYDIAL INFECTIONS

Oral antibiotics are the standard treatment for chlamydial infections, which can be easily cured (CDC, 2021e). Patients with chlamydial infections should not have sexual intercourse until a week after the beginning of their treatment regimen. Although guidelines exist for the treatment of chlamydia, the healthcare provider must individualize the treatment regimen to meet the specific needs of each individual.

CHLAMYDIA TREATMENT REGIMES

Typical multiple-dose treatment:- Doxycycline 100 mg orally 2x/day for 7 days

- Azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose

- Levofloxacin 500 mg orally 1x/day for 7 days

For pregnant patients:

Typical treatment:- Azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose

- Amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3x/day for 7 days

(Workowski et al., 2021)

CASE

Chlamydia

Marie is a 22-year-old college student who seeks care at University Health Services because she has noted a new-onset vaginal discharge. Marie shares with Gail, the women’s health nurse practitioner, that she is in a new relationship and has not used condoms during sexual activity since she is taking birth control pills. Following a discussion about STDs, Marie and Gail agree that a pelvic examination and STD testing are needed. During the examination, the nurse practitioner notes a mucopurulent endocervical discharge and obtains a specimen for nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT).

Gail explains that she suspects that Marie has chlamydia and that the NAAT will provide a definitive diagnosis. In the meantime, Gail initiates presumptive treatment and writes a prescription for doxycycline 100 mg to be taken twice a day for seven days. Additionally, the nurse practitioner explains the need to abstain from sexual intercourse until Marie has completed the seven days of antibiotics and the vaginal discharge has resolved.

The nurse practitioner also discusses the need for Marie’s sexual partner to receive treatment so that the infection is not passed back and forth. Marie agrees to tell her sexual partner her diagnosis and the need for him to receive treatment.

Gail recommends that Marie receive annual STD testing since she is sexually active and in the high-risk age group for STDs such as chlamydia. Gail also explains the importance of using condoms consistently during sexual intercourse. She further explains that birth control pills prevent pregnancy but do not protect against the transmissions of STIs.

Gail later receives confirmation of the diagnosis of chlamydia and calls Marie to tell her the diagnosis and to reinforce the importance of abstaining from sexual intercourse until symptoms resolve and the course of antibiotics are complete. Marie tells Gail that her partner reports being asymptomatic but has agreed to testing and has made an appointment at the health clinic.

Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is an infection of the mucous membranes caused by the diplococcus N. gonorrhoeae. It can be transmitted through sexual contact with the penis, vagina, mouth, or anus. It is about one third as common as chlamydial infections, although the two infections frequently coexist in an infected person. Untreated, gonorrhea also increases a person’s risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. In 2019, approximately 616,392 new cases of gonorrhea were reported in the United States, and it is the second most common notifiable condition. Adolescents and young adults ages 15–24 years are at the highest risk for infection (CDC, 2021h, 2021s).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

In men, N. gonorrhoeae causes gonorrheal urethritis, producing symptoms such as pain or discomfort on urination and a purulent urethral discharge (CDC, 2021h). Untreated gonorrheal urethritis can develop into epididymitis (Workowski et al., 2021).

In women, N. gonorrhoeae that have invaded the urethral opening produce gonorrheal urethritis, and N. gonorrhoeae that have invaded the vagina produce gonorrheal cervicitis. Most women with urethral or cervical gonorrhea have mild or no symptoms and may infect sexual partners unwittingly (CDC, 2021t). When symptoms do occur, they can include purulent and sometimes odorous vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding after intercourse, and pain or discomfort on urination. Gonorrhea can also infect the Bartholin’s glands. Untreated gonorrheal cervicitis sometimes ascends into the uterus and leads to PID, which typically presents with lower abdominal pain. On speculum examination, gonorrheal cervicitis appears as a swollen, friable cervix with a mucopurulent exudate.

Untreated, patients with a gonorrheal infection develop gonorrheal bacteremia with fever and, occasionally, septic arthritis. Gonorrheal bacteremia is also known as disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI). DGI is usually characterized by arthritis, tenosynovitis, and dermatitis and can be life threatening (CDC, 2021h). The untreated disease can also cause scarring of the Fallopian tubes, leading to infertility or tubal pregnancies.

It is also common for patients with gonorrhea to have trichomoniasis. In both males and females, oral sex can lead to gonococcal pharyngitis and anal sex to gonococcal proctitis. In the newborn, it manifests as a conjunctivitis that can cause blindness.

This male presented with a purulent penile discharge and overlying penile pyodermal lesions located on the glans penis, due to gonorrhea. (Source: CDC/Jo Miller, Public Health Image Library.)

This colposcopic view of a patient’s cervix revealed an eroded ostium due to Neisseria gonorrhea infection. (Source: CDC, Public Health Image Library.)

SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS OF GONORRHEA

Gonorrhea infections are difficult to distinguish clinically, and lab tests are needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

It is recommended that two subpopulations have regular gonorrheal screenings and be counseled about the importance of using condoms:

- Sexually active women younger than 25 years of age

- Sexually active women age 25 and older who have a new sex partner, multiple partners, a partner who has other partners, or a sex partner who is a sex worker or who has an STI

- All pregnant women younger than 25 years of age

- Pregnant women 25 years of age and older who have a new sex partner, multiple partners, a partner who has other partners, or a sex partner who is a sex worker or who has an STI (CDC, 2021i)

- Men who have sex with men, who should receive screening for rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal gonorrhea

(CDC, 2021i; CDC, 2021u)

People younger than 25 years, including sexually active adolescents, are at risk for gonorrhea infection, but there are no recommendations for screening due to insufficient evidence of its effectiveness in that age group.

Light microscopic examination of a sample of urethral discharge can diagnose gonorrhea in men. In male gonorrheal urethritis, stained microscope slides will show Gram-negative diplococci. For women, a more sensitive and specific test is needed, and NAATs of urine or of a swab of the affected area are the preferred test techniques (CDC, 2021h). Urine samples can be used to test for urethritis in all genders.

Vaginal swab specimens are used to test for cervicitis. Gonorrheal cervicitis produces sufficient discharge that swabs need not be taken by speculum examination. Instead, they can be collected blindly by the patient.

For oral or anal gonorrhea, pharyngeal or rectal swabs are taken and sent to the lab for culturing.

TREATMENT OF GONORRHEA

As with many STIs, the highest rates of successful treatments come when antimicrobial medicines can be taken in single doses administered at the time of diagnosis. Antimicrobial resistance is a growing problem in the treatment of gonorrhea, making eradication of the infection challenging in some individuals (CDC, 2021h). Although guidelines exist for the treatment of gonorrhea, the healthcare provider must individualize the treatment regimen to meet the specific needs of each individual.

GONORRHEA TREATMENT REGIMES

For uncomplicated urogenital or anorectal gonorrhea (including for pregnant patients):

- Ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly (this can be reconstituted in 1% lidocaine to reduce pain in the injection area)

- Ceftriaxone 1 gm for those weighing 150 kg or more

For patients with penicillin or cephalosporin allergies:

- Dual treatment with single doses of intramuscular gentamicin 240 mg plus oral azithromycin 2 g, or

- Oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg in a single dose, if the person has no symptoms and gyrase A testing can be performed to identify ciprofloxacin susceptibility

For pharyngeal gonorrhea:

- Ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly in a single dose, ceftriaxone 1 gm for those weighing 150 kg or more

(CDC, 2021j)

DRUG RESISTANCE AND TREATMENT CONCERNS

One difficulty in treating gonorrhea is that it has developed resistance to the fluoroquinolone antibiotics used to treat it, leaving the cephalosporin antibiotics as the only recommended treatment. If a cephalosporin-resistant gonorrhea were to emerge, this STI would become very difficult to treat (CDC, 2021v).

Patients with gonorrhea often have other STDs/STIs and are therefore tested for HIV, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and syphilis. They are also offered hepatitis B vaccination if they have not already been vaccinated.

Patients with uncomplicated urogenital or rectal gonorrhea who receive standard treatment recommendations do not require retesting for infection. Patients with pharyngeal infection are retested in 7–14 days using NAAT or cultures. However, if NAAT testing is positive, a culture should be obtained for antimicrobial susceptibility before receiving retreatment (CDC, 2021j).

Although treatment for gonorrhea is usually successful, patients with gonorrhea may become reinfected. Therefore, as for people with chlamydial infections, patients treated for gonorrhea are advised to return in three months for rescreening.

CASE

Gonorrhea

Rogelio, a 32-year-old male, is being seen by his primary care provider, Tara, for what Rogelio believes is a urinary tract infection due to pain on urination. His history reveals that Rogelio has had one sexual partner for the past two months and that condoms are not consistently used. On physical examination, Tara notes a reddened and swollen scrotum and discharge from the urethra. She obtains a swab of the discharge and performs light microscopic examination, noting Gram-negative diplococci consistent with gonorrhea. She also performs testing for chlamydia, which is negative. Tara then asks Rogelio if his partner has had any symptoms, and he states he is not aware of any.

Since Rogelio weighs 62.6 kg, Tara administers ceftriaxone 150 mg intramuscularly, in a single dose, to treat the gonococcal infection. Tara tells Rogelio that it is important that he notify his sexual partner that she may have gonorrhea and needs to be treated. Rogelio tells Tara he will have a discussion with his partner that evening. Tara also tells Rogelio that he must refrain from sexual intercourse until seven days after treatment of himself and his partner.

Rogelio calls the clinic the next day and reports that his partner has refused to go to the clinic for testing. Tara explains that because they live in a state in which expedited partner therapy is allowed, she can prescribe oral antibiotics for Rogelio’s partner to take at home, although this is not the recommended IM route of antibiotic administration to treat gonorrhea. Tara calls a prescription to the pharmacy for cefixime 800 mg given orally as a single dose. Even though an oral antibiotic is not as effective in the treatment of gonorrhea, it is important that Rogelio’s partner receive treatment. Moreover, for maximum adherence, it is recommended that antibiotics be taken under direct observation of a clinician.

Syphilis

Syphilis is caused by the bacterium T. pallidum. In the United States, 133,945 new cases of syphilis were reported in 2020, with men who have sex with men accounting for 43% of all primary and secondary symphilis cases. Case rates are also increasing among heterosexual men and women in recent years (CDC, 2021k, 2021s).

Syphilis is transmitted by sexual contact. Pregnant women with syphilis can also transmit the disease to their newborn baby at the time of birth. The infant can then develop congenital syphilis, which when untreated can delay development, cause seizures, or even be fatal. Congenital syphilis is now referred to as a mother-to-child transmission and is projected to be eliminated from countries with limited resources by rapid method testing and a single injection of penicillin given antepartum (Fan et al., 2019).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

A syphilis infection begins locally and slowly spreads systemically. Over time, untreated syphilis will go through stages with different signs and symptoms. It can be fatal if untreated because of potential damage to the brain, heart, or nervous system. A person may come to a clinician initially with primary syphilis (i.e., a local genital infection) or a few months later with secondary syphilis (i.e., a systemic infection). The stages of syphilis infection are as follows:

- Primary syphilis. The hallmark of primary syphilis, a local infection, is the appearance of an ulcer called a chancre. Typically, there is only one chancre, located at the site of infection on the penis, vulva, cervix, perianal region, or oral mucosa. The chancre appears a few weeks after T. pallidum bacteria have invaded the skin. The incubation period is approximately 3 weeks. A syphilis chancre typically has firm, raised edges and a smooth internal base and is painless. Local lymph nodes may be enlarged. If untreated, chancres heal spontaneously in 3–6 weeks, leaving faint scars. Even if the chancre has disappeared, the infected person is very contagious during this phase of the disease (CDC, 2021k).

- Secondary syphilis. When primary syphilis is not treated, the chancre disappears for a few weeks and then reappears as secondary syphilis. Secondary syphilis is a systemic infection with flu-like symptoms (low-grade fever, headache, malaise, generalized lymphadenopathy) and a widespread, symmetrical, non-itchy maculopapular rash, first on the trunk and arms and later the palms and soles. The genital area may also have wart-like papules. During secondary syphilis, a person can develop syphilitic hepatitis or syphilitic glomerulonephritis.

- Latent syphilis. When secondary syphilis is untreated, the symptoms usually fade and the disease becomes quiescent, sometimes for years. This asymptomatic interim stage is called latent syphilis.

- Tertiary (late-stage) syphilis. Although rare, untreated syphilis may reemerge and cause symptomatic damage to a variety of organs. This can occur 10–30 years after the initial infection (CDC, 2021k). This is the final form of the disease, and it produces granulomatous or necrotic lesions that can involve the skin, eyes, central nervous system, heart, aorta, or bones. Today, tertiary syphilis is rare except in patients with a concurrent HIV infection.

SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS OF SYPHILIS

Routine screening for syphilis is recommended for:

- Patients with any newly diagnosed STD/STI

- Patients at high risk for STDs/STIs

- All pregnant women

The laboratory tests to screen for syphilis include Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL), rapid plasma reagin (RPR), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed (FTA-ABS), and T. pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA). Diagnoses are more likely to be made using blood tests (CDC, 2017l).

The RPR and VDRL are called nontreponemal serologic tests because they are not specific for syphilis. False-positive nontreponemal serologic tests occur in patients with autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus and in a few other special populations. It usually takes at least a week after a patient acquires syphilis for these antibody tests to become positive.

People who have syphilis are more likely to have acquired other STIs. Therefore, patients with syphilis should also be tested for HIV, hepatitis B and C, chlamydia, and gonorrhea.

A primary syphilitic lesion, also known as a chancre, can be seen on the penile corona on the right side of the glans penis. The lesion is accompanied by enlargement of the bilateral inguinal lymph nodes. (Source: CDC/Susan Lindsley, Public Health Image Library.)

Perianal condylomata lata lesions due to secondary syphilis can be seen in perineal region of a female patient. (Source: Public Health Image Library.)

TREATMENT OF SYPHILIS

Intramuscular benzathine penicillin G is the treatment of choice for syphilis. In the first days after syphilis treatments, some people get a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (i.e., fever, myalgia, tachycardia, headaches, and hypotension), informally called Herx, which should not be mistaken for an allergic reaction. Reacting patients are treated with bed rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Although guidelines exist for the treatment of syphilis, the healthcare provider must individualize the treatment regimen to meet the specific needs of each individual.

SYPHILIS TREATMENT REGIMES

For primary and secondary syphilis in adults:

- Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly in a single dose

For latent syphilis in adults:

- Early latent phase: Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly in a single dose

- Late latent phase: Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly, in 3 doses, at 1-week intervals

For infants and children:

- Benzathine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg (up to 2.4 million units) intramuscularly in a single dose

For patients allergic to penicillin, either oral doxycycline or oral tetracycline is given for 14 days. During pregnancy, however, only penicillin can be given to treat syphilis. Therefore, pregnant women who are allergic to penicillin should first be desensitized to and then treated with penicillin.

(Workowski et al., 2021)

After treatment, patients should be retested at 6, 12, and 24 months for the presence of nontreponemal antibodies. Within a year, the patient’s nontreponemal antibody titers should have decreased at least fourfold. On the other hand, tests for treponemal antibodies will remain positive even after adequate therapy.

For pregnant women with syphilis treated at 24 weeks or earlier, titers should be tested after 8 weeks of treatment and again at delivery. Pregnant women who are treated after 24 weeks of gestation should have titers tested again at delivery (Workowski et al., 2021).

TREATING SEXUAL PARTNERS

Patients with early syphilis (i.e., primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis) are contagious. People who in the preceding three months have had sexual contact with a patient with early syphilis should be notified and treated. Treatment is recommended even for those contacts with no clinical or serologic evidence of the disease (Workowski et al., 2021).

CASE

Syphilis

Marquis, 26-years-old, is seeing his primary care provider, Vedant, because he is concerned about a sore that appeared on his penis one week ago. During the history, Vedant learns that Marquis engages in condomless sex with other men. An examination reveals a chancre with firm raised edges on the underside of the penis, which Marquis reports is painless. Inguinal lymph nodes are enlarged bilaterally.

Vedant suspects that Marquis has primary syphilis and orders VDRL (nontreponemal) and TPPA (treponemal) tests. Since individuals with syphilis are also at risk for other STIs, Vedant explains the need to test for HIV, hepatitis B and C, chlamydia, and gonorrhea.

Vedant explains to Marquis that he is contagious and that anyone with whom he had sexual contact with in the preceding three months must be notified and treated. Vedant explains that the local health department can help Marquis notify his partners of the need for testing and treatment. Marquis declines this service since he feels capable of speaking with his partners about the need for medical care.

Marquis is treated before leaving the office with a single dose benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly. Vedant explains the need to avoid sexual contact until Marquis’s chancre is healed. Vedant also explains the need to consistently use condoms to avoid the transmission of STIs and that transmission can occur if the sore or lesion is not covered by the condom. Marquis understands that his risks for STIs increases with multiple sex partners.

Marquis verbalizes the need to return for retesting at 2, 12, and 24 months. Vedant explains that within a year, nontreponemal antibodies should be reduced fourfold. If this does not occur, Marquis may need to be treated again. Treponemal antibodies will, however, remain positive.

Genital HPV Infections

HPV infection, caused by small DNA viruses, is the most common STI in the United States. HPV is so common and contagious that almost all sexually active adults will have had at least one genital HPV infection during their lives if they are not vaccinated, and it is estimated that 1 in 100 of every sexually active person has genital warts caused by HPV at any given time. About 14 million people become newly infected each year (CDC, 2020c). About half of the new cases occur in people ages of 15–24. Women are more susceptible to acquiring genital HPV infections than are men. As with other STIs, HPV infections are most common in people with more than one sexual partner (CDC, 2021m; Workowski et al., 2021).

Hundreds of HPV types have been characterized, and approximately 40 of these can infect humans. Benign HPV lesions such as genital warts are caused by low-risk types of HPVs (e.g., HPV types 6 and 11). Rarer, malignant HPV lesions such as cervical cancer and cancers of the anus, penis, vagina, or vulva can be caused or facilitated by high-risk types of HPV (e.g., HPV types 16 and 18).

HPV infections can be sexually transmitted even when an infected person has no visible symptoms, and a condom is used. The common types of genital HPV infections can cause anogenital warts, called condyloma acuminata. HPV types 16 and 18 appear to cause the majority of cervical, vulvar, or penile cancer. HPV infections often disappear spontaneously or may need to be excised (CDC, 2021m; Workowski et al., 2021).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Many HPV infections are asymptomatic, but some types of HPV infections cause common skin warts and plantar warts, while other types of HPV infections may cause genital warts and cancer of the vulva, vagina, penis, anus, or back of throat (Mayo Clinic, 2021b; CDC, 2021m).

Genital warts can also develop beyond the genitals. Perianal genital warts can be acquired by skin-to-skin contact, but intra-anal genital warts are transmitted through anal intercourse. Very rarely, newborns can be infected by HPV during the birth process (Syrjänen et al., 2021).

Most HPV infections are short-lived and spontaneously disappear in less than a year without causing clinical problems. However, HPV can cause cancer of the cervix as well as the vulva, vagina, penis, anus, and oropharynx. It can take years to decades for cancer to develop after contracting HPV (CDC, 2021m).

The aberrant cell growth caused by high-risk HPVs leads to squamous cell dysplasias (e.g., cervical dysplasia) and eventually to neoplasms, such as cervical intraepithelial neoplasias, squamous cell cancers, anal squamous cell cancers, or adenocarcinomas. HPV dysplasias in the cervix can usually be detected by Pap tests (NCI, 2021).

Genital warts vary widely in size. They can be as tiny as a pinhead or as large as a small cauliflower (1 cm to 2 cm in diameter), and they can occur singly or in clusters. The small warts tend to be on stalks. Genital warts are typically found on moist surfaces such as the labia, vagina, cervix, urethra, bladder, perianal skin, or anus. In women, the walls of the vagina and the surface of the cervix can also have genital warts (which are often flat patches). When external warts are present, women should have a speculum exam to search for internal warts.

In all genders, genital warts can grow along the internal walls of the urethra or bladder. Large or extensive warts around the urethral meatus indicate that the internal urinary tract should also be examined for warts.

Soft, wart-like growths caused by HPV can be seen on the penile shaft. The areas most commonly affected by genital warts are the penis, vulva, vagina, cervix, perineum, and perianal area. (Source: CDC/Dr. M. F. Rein, Public Health Image Library.)

A close view of the anal region of a male patient shows the presence of condylomata acuminata (genital warts). (Source: Public Health Image Library.)

SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS OF GENITAL HPV INFECTIONS

A variety of organizations suggest that all women ages 21–29 years should have a cytology (Pap) test to screen for cervical cancer every three years. For women ages 30–65 years, a cytology test should be performed every three years, an HPV test every five years, or a cytology and an HPV test (co-testing) every five years. Cervical screening recommendations are the same for women who have received the HPV vaccine (CDC, 2021n).

HPV cannot be cultured. On the other hand, DNA from HPV viruses can be tested to determine whether the virus is one of the high-risk types. DNA testing and type classing are used to make judgments about dysplasias with unclear cytologic test results, and DNA tests are also a common adjunct to Pap testing of women older than 30 years of age. Tissue testing after biopsy provides a definitive diagnosis, as do PCR assays (Harding et al., 2020).

Genital warts, like cutaneous warts, can usually be diagnosed by their appearance, symptoms, and history. Genital warts caused by low-risk HPVs are soft, raised, skin-colored, and nontender. Most genital warts are asymptomatic, although sometimes they cause itching or burning (CDC, 2021m).

HPV VACCINATION

There are three vaccines to prevent HPV licensed in the United States:

- 2vHPV, effective against HPV types 16 and 18

- 4vHPV, effective against HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18

- 9vHPV, effective against HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

As of 2021, the only vaccine available in the United States is 9vHPV. HPV types 16 and 18 are responsible for 66% of cervical cancers, while HPV types 6 and 11 are linked to more than 90% of cases of genital warts.

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends the following vaccination practices for HPV (Meites et al., 2019):

- Two doses of HPV vaccine in boys and girls ages 9–12 years

- Catch-up vaccination for those up to age 26 years who have not previously received the HPV vaccination

Ideally, the vaccination should be given before a female is sexually active because it does not protect against existing HPV infections. The current HPV vaccine does not protect against all potentially cancer-causing types of HPV. Therefore, all women—even those who have been vaccinated against HPV—should have regular Pap tests.

The vaccine can also prevent genital warts and anal cancers in males and may help to prevent cancers of the oropharynx and penis (ACIP, 2018).

TREATMENT OF GENITAL HPV INFECTIONS

HPV infection itself cannot be treated, but lesions caused by the virus are treated by removal, which reduces infectivity but does not remove the presence of the virus.

About 25% of all genital warts will disappear on their own; nonetheless, most clinicians and patients elect to remove the warts. After treatment, the virus is still in the surrounding epithelium, and approximately one third of patients will have a recurrence of the warts. In addition, HPV infections are commonly reacquired from the patient’s sexual partner(s).

For squamous cell dysplasias, treatment is usually excision. Dysplasias are referred to a specialist for medical management.

GENITAL WARTS TREATMENT REGIMES

For small areas (less than 10 cm2) of genital warts, patients can often treat themselves with topical chemicals. It may be necessary to apply these topical drugs for many weeks. It should be noted that for several hours these chemicals can affect the efficacy of condoms.

Typical patient-applied treatments for external anogenital warts are either:

- Imiquimod 5% cream applied to warts 1x/day at bedtime 3 days per week for less than 16 weeks, or

- Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel applied to warts 2x/day in cycles of 3 days of treatment alternating with 4 days of no treatment, may repeat up to 4 cycles, or

- Sinecatechin 15% ointment applied 3x/day, not to continue beyond 16 weeks

Healthcare provider–applied treatments include:

- Cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen or cryoprobe)

- Chemicals (trichloracetic acid or bichloroacetic acid)

- Surgical excision (tangential scissor excision, shave excision, curettage, laser, or electrosurgery)

For pregnant patients:

- Podofilox, podophyllin, and sinecatechins should be avoided during pregnancy.

- While imiquimod appears to have a low risk (pregnancy category C), it should not be used until more research is obtained.

(Workowski et al., 2021)

CASE

HPV Vaccination

A mother brings her 13-year-old daughter, Rosa, to the pediatrician’s office for her annual well-child check-up. They are seen by Luanne, a pediatric nurse practitioner. Much to Rosa’s embarrassment, her mother starts asking the nurse about “this vaccine for genital warts I’m hearing about on TV. Does Rosa need that if she’s not having sex yet?”

Luanne explains to both Rosa and her mother that the vaccine is a series of injections that protect Rosa from HPV, the virus that causes genital warts. She explains that these warts may cause cervical cancer later in life. The recommendation is that girls receive the immunizations before they are sexually active and can get the warts. Luanne also points out that immunizations are only effective if they are given before exposure to the infection.

The mother thanks Luanne and asks if there is an HPV vaccine for her 11-year-old son. Luanne explains that genital warts in men and boys can become cancerous as well and that the vaccine is also recommended for boys. The mother says she will “think about it and look up some more about it on the Internet.” Luanne offers to answer any questions that may occur later and gives a pamphlet to both Rosa and her mother.