MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE CAD

Patients with CAD may have mild symptoms (stable angina) that can be monitored and treated over time. Other patients may present with chest pain, dyspnea, profuse sweating, extreme fatigue, or other acute symptoms that may need to be seen in an emergency department and evaluated immediately.

Emergency Treatment

Emergency treatment for patients with CAD can be guided by the American Heart Association’s “chain of survival,” a series of actions that, when put into motion, can reduce the patient’s chance of dying from cardiac arrest. The six links in the adult out-of-hospital chain of survival are:

- Recognition of cardiac arrest and activation of the emergency response system

- Early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with an emphasis on chest compressions

- Rapid defibrillation

- Advanced resuscitation by emergency medical services and other healthcare providers

- Post–cardiac arrest care

- Recovery (including additional treatment, observation, rehabilitation, and psychological support)

(AHA, 2021e)

Unless patients have already been diagnosed with stable angina and recognize that they are having a typical short-lived anginal attack, they should call 911 and be transported quickly by emergency responders to an emergency department whenever experiencing an episode of chest pain.

BEFORE THE HOSPITAL

Because quick treatment of an MI is so beneficial, bystanders should start cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) as soon as they see someone collapse, call 911, and use an automated external defibrillator (AED) if one is available.

Emergency response professionals (EMT and/or nurses) who encounter patients experiencing chest pain or a sudden onset of dyspnea should treat the symptoms as myocardial ischemia and begin active interventions.

According to the ACLS Training Center (2021), the immediate actions to treat acute coronary syndrome include:

- Monitor and support CABs (circulation, airway, breathing)

- Monitor vital signs

- Monitor the cardiac rhythm

- Administer CPR, if necessary

- Use a defibrillator, if necessary

- If the patient’s pulse oximetry is less than 94%, administer oxygen at a level that increases the saturation to 94%–99%. If the patient has a history of COPD, administer oxygen if pulse oximetry falls below 90% on room air.

- If the patient is short of breath, administer oxygen no matter what the oxygen saturation reveals.

- Obtain a 12-lead ECG.

- Interpret or request an interpretation of the ECG. If ST elevation is present, transmit the results to the receiving hospital. Hospital personnel gathers resources to respond to STEMI. If unable to transmit, the trained prehospital provider should interpret the ECG, and the cardiac catheterization laboratory should be notified based on that interpretation.

In addition to the above emergency procedures:

- Start an intravenous (IV) access for the purpose of administering emergency medications, if necessary.

- Have a conscious patient chew and swallow 325 mg of aspirin.

- Administer sublingual NTG by tablet or spray every 5 minutes X 3.

If the pain is unrelieved by NTG, give a narcotic pain reliever such as fentanyl, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), or morphine sulfate. Morphine is the drug of choice for a myocardial infarction, given its properties of preload and afterload reduction.

ANSWERING PATIENT QUESTIONS

Q:I think I’m having a heart attack, but I’m not sure. Should I call my doctor? Should I drive to the hospital?

A:Don’t waste time calling your doctor, and don’t take any chances. Don’t drive yourself to the hospital. Instead, call 911 immediately. Emergency medical technicians can start to treat you on the way to the hospital. While you wait for the ambulance, if you can, chew one regular aspirin (325 mg) or four baby aspirins (81 mg each), then sit down and try to relax.

Q:But I would be embarrassed having an ambulance zooming up to my house with lights flashing and sirens blaring. It would be even worse if I weren’t really having a heart attack.

A:Of course, those are normal feelings. The paramedics in the ambulance and the healthcare professionals in the emergency department know that it isn’t easy for a person to figure out if they are really having a heart attack. They also know that when people wait too long to get help, they are more likely to die. No one will give you a hard time if you are not actually having a medical crisis.

If there is even a small chance that you could have a heart attack, your primary care provider may have already warned you. Your life is worth more than a little embarrassment, so call 911 if there is any possibility that you might be having a heart problem.

IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT (ED)

Triage

When a patient experiences ischemic heart symptoms, it is potentially a life-threatening emergency. Triage of patients with acute chest pain by the medical team in the ED includes the following assessment steps, coordinated by the ED physician in conjunction with the nurse conducting the initial medical screening examination:

- Upon presentation to the ED with symptoms suggestive of an acute coronary syndrome, the patient is immediately taken to a room.

- The ED physician assesses for and reverses circulatory system failure and respiratory insufficiency.

- When clinically stabilized, the patient is assessed for immediate life-threatening conditions (medical crises associated with chest pain):

- Cardiovascular

- Acute, massive myocardial infarction

- Pulmonary embolism

- Aortic dissection

- Cardiac tamponade

- Pulmonary

- Pulmonary embolus

- Tension pneumothorax

- Working together with the ED physician, the nurses’ responsibilities may include assessing the patient’s complaints, symptoms, and vital signs. Patients presenting with the complaint of chest pain are evaluated with a focused history and physical examination conducted by a physician. Chest pain typically requires additional diagnostic testing, including ECG, chest X-ray, and blood tests for cardiac markers of ischemic heart injury.

The ED nurse monitors the patient’s basic vital signs and cardiac monitor at regular intervals for the development of any dysrhythmias.

Older patients (>75 years), patients with diabetes, and female patients are more likely to present with the sudden onset of dyspnea and fatigue as the primary symptom of an acute coronary syndrome, and new dyspnea can be the equivalent of chest pain in these individuals. Nausea and vomiting may also accompany these symptoms.

Evaluation of Stabilized Patients

After stabilizing patients, a triage protocol for chest pain/sudden dyspnea is implemented.

It is important for the team of providers in the ED to remember that one third of people with acute myocardial infarction do not mention chest pain as their chief complaint. Many patients are more likely to describe other symptoms as their primary complaint, even when they are suffering a heart attack.

Atypical presentations tend to come from patients with diabetes, older adults, women, patients of non-White ethnicities, and patients with dementia. Besides dyspnea, atypical symptoms include nausea; profuse sweating; fainting; and pain in the neck, shoulder, arms, or upper abdomen.

To begin the medical evaluation of a patient with stable chest pain, the triage physician working with a stabilized adult patient may order an immediate 12-lead ECG to look for STEMI. It is thought that patients with STEMIs usually have a completely blocked artery, whereas patients whose infarctions do not produce ST elevations have an incompletely blocked artery (Lewis et al., 2020).

Treatment of STEMI

Fast treatment gives the best outcome for all myocardial infarctions. Certain types of myocardial infarction will benefit dramatically from quick reperfusion therapies, drugs, and other techniques that open the blocked arteries and restore blood flow.

Heart damage does not happen all at once after the blockage of a coronary artery; a myocardial infarct continues to enlarge over 5 to 6 hours if the blockage is not reduced or removed. After the initial infarction, an area of ischemia known as a corona (crown) surrounds the infarcted tissue. It is this ischemic tissue that may become infarcted if reperfusion of the area is not established.

For these reasons, the AHA criteria recommend that emergency departments aim for reperfusion within 90 minutes of admission to the hospital, with an emphasis of treating STEMI patients within 90 minutes. The mortality rate from a STEMI can be decreased by about half if the blocked arteries are reopened in the first 90 minutes after the symptoms begin. Quick reperfusion therapy will also reduce the amount of permanent muscle damage resulting from a STEMI.

Since reperfusion may be accomplished by thrombolytic drugs or dilation of the blocked artery, this 90-minute duration is referred to as “door-to-balloon” time (first intra-aortic device used). If the patient is initially admitted to a non-PCI hospital (i.e., lacks the capacity to perform a percutaneous coronary intervention), the “door-to-balloon” or “door-to-device” time must include the transfer to a PCI hospital (Nathan et al., 2020).

When STEMI is identified, a reperfusion plan is formulated for the patient by the triage team. The two major choices for reopening a blocked artery are pharmacologic and mechanical. The pharmacologic option is administration of a fibrinolytic or thrombolytic drug therapy, unless contraindications exist, to weaken and disrupt the damaging clot. The mechanical option consists of a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), also known as PTCA (percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty), meaning balloon angioplasty with or without the placement of a stent, to break up or remove the clot. Most recently, PCI is performed more often than administration of thrombolytics.

Thrombolytic or fibrinolytic drugs may be given after a STEMI to dissolve a blood clot that is completely occluding a coronary artery. These drugs are also familiarly called “clot busters.” They are administered as soon as possible after a diagnosis is made and this form of reperfusion is chosen. They are given slowly by intravenous infusion over a period of 30–90 minutes, depending on the drug.

Two possible side effects of thrombolytics are so potentially dangerous that they are only administered in an ED or an ICU where the patients can be closely monitored by critical care nurses. The more common side effect is reperfusion dysrhythmias. This is an accelerated idioventricular rhythm, or a heart rhythm initiated in the ventricles at a rate faster than the inherent rate of the ventricles (>70 beats per minute). The cause is a rapid return of blood perfusing the ischemic myocardial tissue. For this reason, the patient’s heart is monitored continuously, although the rhythm usually returns quickly to normal.

Thrombolytics dissolve the blood clot that is blocking one or more coronary arteries. They may also dissolve other blood clots, causing hemorrhage. This is a rare but much more dangerous potential side effect.

CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR THROMBOLYTICS

Absolute (will never be given):- Previous intracranial bleeding

- Vascular malformation

- Intracranial tumor

- Ischemic stroke within past 3 months

- Closed head or facial injury within past 3 months

- Intracranial or intraspinal surgery within past 2 months

- Severe uncontrolled hypertension

- Active internal bleeding

- Suspected aortic dissection

- Active peptic ulcer disease

- Use of oral anticoagulants

- Pregnancy

- Ischemic stroke >3 months ago

- Dementia

- Intracranial pathology

- Noncompressable vascular punctures

- Recent (2–4 weeks) internal bleeding

- Major surgery <3 weeks

- History of chronic, severe, poorly controlled hypertension

- Current BP >180/110

- Traumatic or prolonged (>10 minutes) cardiopulmonary resuscitation

(Lewis et al., 2020)

Commonly used thrombolytic agents include:

- Tissue plasminogen activator (TPA)

- Alteplase

- Reteplase

- Tenecteplase

- Lanoteplase

(Lewis et al., 2020)

Percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) are an invasive form of reperfusion therapy. They have more potential risks and are more expensive than drug therapy. They must be performed in a facility with a cardiac catheterization laboratory (cath lab) or interventional radiography department (IR), often limiting the ability to perform reperfusion within the desired 90-minute goal. These are usually performed by a cardiologist. (See also “Percutaneous Coronary Intervention” below).

Distinguishing a STEMI from an NSTEMI infarction is important. Either reperfusion technique will benefit STEMI patients when done quickly. Patients without the characteristic ECG changes of STEMI may have either NSTEMI infarction or unstable angina.

Additional diagnostic tests coordinated by the triage physician for all chest pain/sudden dyspnea patients include a chest X-ray. As the patient is evaluated, the nurse continuously makes assessments for changes in symptoms, vital signs, and blood oxygen levels, since these are important indicators of a worsening medical condition. ECGs may also be repeated. Serum cardiac markers will be measured to determine whether reperfusion has caused a release of protein into the blood.

Stabilized patients who are unlikely to have an acute coronary syndrome still need to be evaluated for the cause of their chest pain. The ED physician conducts a thorough patient history to uncover underlying causes for chest pain. Among the causes that are considered include pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, pericarditis, rib fracture, costochondral separation, esophageal spasm, aortic dissection, renal calculus, splenic infarction, abdominal disorders, or chest injuries (Sole et al., 2021).

CASE

Nelson Martinez is a slightly overweight, 56-year-old Hispanic male with a history of hypertension, CAD, and chronic stable angina. At a family gathering in a local park, he joined in on a soccer game but started to feel nauseated and short of breath after running around for a few minutes. Because he has a history of heart disease and angina, his wife called 911, and an ambulance brought him to the closest emergency department.

Nelson was admitted to the ED 30 minutes after his angina symptoms emerged. He described his initial symptoms as shortness of breath, nausea, and arm pain to the nurse in the ED. The nurse recognized these as possible myocardial ischemia and immediately initiated the chest pain protocol along with the medical team. This included a chest X-ray, a 12-lead ECG, starting an IV, administering 325 mg of oral aspirin to be chewed, drawing blood, and initiating oxygen therapy. The nurse communicated this to Mrs. Martinez and explained the process of assessment of the chest pain in order to stabilize her husband’s angina. Mrs. Martinez was reassured by the nurse that she did the right thing by calling 911, since quick treatment can improve outcomes.

The ECG revealed a ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The physician ordered the administration of a fibrinolytic drug to achieve reperfusion. The nurse working with Mr. Martinez explained the indication for the therapy to the patient and his wife by educating them about ST elevations and the need to treat symptoms quickly in order to provide blood supply to the heart muscle. The nurse helped Mr. Martinez to sign a consent for the procedure after the possible risks and benefits of the procedure were explained. She reassured Mr. Martinez and his wife that he would be monitored on a cardiac monitor continuously during and after the procedure and that he would be observed and have frequent vital signs taken the entire time the medication was infusing.

Because of the quick action by Mrs. Martinez and the identification of the STEMI, Mr. Martinez was treated within 60 minutes after his first symptoms appeared. His condition was stabilized, and he was admitted to the cardiology service for further monitoring of his symptoms.

Goals of ED Care for Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes

For all patients with acute coronary syndromes, the primary goals of care include:

- Revascularize the coronary artery

- Stabilize heart rhythm

- Preserve myocardial tissue and function

- Reduce cardiac workload

- Provide pain relief

While the type of acute coronary syndrome is being identified, the following medical treatments may be ordered for the patient:

- Supplemental oxygen ensures that the existing blood supply is maximally oxygenated.

- Antiplatelet drugs are a key treatment. Aspirin taken daily reduces the mortality from an acute myocardial infarction, unless contraindications exist (such as coagulopathies), and all conscious patients with a possible acute coronary syndrome should have chewed and swallowed 325 mg of nonenteric-coated aspirin. Aspirin can also be given as a suppository.

- Fibrinolytic drugs (TPA, alteplase, tenecteplase, lanoteplase, or reteplase) are also utilized, unless contraindications exist, to weaken and disrupt the damaging clot in the coronary artery. Thrombolytic therapy can be used within three hours of the onset of symptoms.

- Vasodilators can increase blood flow to heart muscle and can reduce the force needed to pump blood through the arterial system. The standard vasodilator for heart arteries is nitroglycerin, which can ease ischemic pain and can also reduce mortality rates. In the ED, nitroglycerin is administered either sublingually, by spray, or via IV. (Certain patients, such as those with hypotension, require graded doses of nitroglycerin and careful monitoring.)

- Beta blockers, such as atenolol, esmolol, metoprolol, or the newer nebivolol, are used to lessen the oxygen requirements of the heart by slowing the heart rate and lowering the arterial tension against which the heart is working (diastolic blood pressure). By reducing the cardiac workload, beta blockers also serve to reduce oxygen consumption, reserving a greater amount of oxygen to be available to the myocardium. Beta blockers also reduce the risk of developing heart dysrhythmias, which can accompany heart ischemia. The use of beta blockers has been shown to minimize the size of infarcts and to reduce mortality rates by as much as 40%.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are administered to patients with evolving MI with ST-segment elevation or left bundle-branch block. ACE inhibitors reduce blood pressure, also reducing cardiac workload, as above.

- Antidysrhythmic drugs, such as amiodarone, vasopressin, and epinephrine, may also be indicated to stabilize heart rhythm if the patient has dysrhythmias.

- Transcutaneous pacing patches or external defibrillation may be needed if serious dysrhythmias continue.

- Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (such as abciximab) may be administered in conjunction with daily aspirin to reduce platelet aggregation if a patient continues to have unstable angina or acute chest pain.

- Anticoagulants can keep new blood clots from forming. Heparin and the low-molecular-weight heparins (e.g., enoxaparin) are often used to lower the risk that unstable angina will progress to myocardial infarction. Heparin administration requires careful monitoring for bleeding, and when the drug is stopped, the patient must be watched for “rebound” ischemic episodes that sometimes occur during the subsequent 24 hours. Low molecular-weight heparins, when given in only therapeutic doses, are much less likely to cause bleeding as a side effect.

- Analgesics (pain relievers), such as morphine sulfate, reduce chest pain and reduce the sympathetic nervous system’s demands on the heart muscles.

- Laser angioplasty, atherectomy, or stent placement may also be initiated during this time (see also “Percutaneous Coronary Intervention” below).

- Emergency cardiac surgery may be performed for patients who are unable to undergo percutaneous interventions (see also “Coronary Artery Bypass Graft” below).

(Lewis et al., 2020)

ANSWERING PATIENT QUESTIONS

Q:My doctor says my medicine is a beta blocker. What’s that, and what is it blocking?

A:A beta blocker is a drug that slows your heart rate and lowers your blood pressure. This kind of drug blocks the stress caused by the nerves that make you tense when you are frightened.

Treating Stable CAD in the ED

Some patients who come to the ED with chest discomfort will have stable angina instead of an acute coronary syndrome. As with all patients with possible heart ischemia, these patients follow a similar treatment protocol, including aspirin, nitroglycerin, a beta blocker, supplemental oxygen, and a blood draw to search for cardiac marker molecules. A common (but incomplete) mnemonic used for the treatment of chest pain in the ED is “MONA treats all visitors” (morphine, oxygen, nitroglycerin, aspirin).

In patients with stable angina, the symptoms that brought them to the ED should resolve and not return over the 2 to 3 hours that they are being monitored. Their ECG and vital signs will remain normal for that patient for the next few hours, and repeated blood tests will find no cardiac marker molecules.

If the evaluation of noncardiac causes of their chest discomfort identifies no serious problems, these patients do not need further medical treatment in the ED. Instead, they can be monitored and followed as an outpatient by a CAD treatment team.

Care of the patient in the ED includes collaborative care with a multidisciplinary team approach. Team members may include emergency medical personnel, nurses, a cardiologist, a cardiothoracic surgeon, respiratory therapists, radiology technologists, venipuncture technicians, and a rehabilitation specialist.

Nursing assessment and care of the cardiac patient in the ED is as follows:

- Assess and monitor vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and heart and breath sounds), communicating any changes to the care team.

- Monitor the patient during episodes of angina and before and after administering medication (especially nitroglycerin and morphine).

- Assess and monitor pain symptoms. Include severity, location, and duration of pain; medications administered; a reevaluation of severity; and any related symptoms.

- Obtain a 12-lead ECG to assess heart rate and dysrhythmias (monitor at admission for a baseline and during acute episodes of angina).

- Assess and monitor urine output hourly or with each voiding.

- Monitor oxygen saturation status continuously and make changes as needed.

- Provide patient education regarding medications administered and any procedures anticipated.

- Communicate changes and status updates to family as needed.

- Assess the patient and family for any ongoing psychosocial needs and refer to appropriate supportive services as needed (e.g., medical social worker, community resources, psychologist, counselor, or clergy).

Interventional Cardiac Procedures and Surgery

Treatment for patients with stable coronary artery disease is medical therapy and lifestyle modification. In some cases, however, surgery or an invasive intervention to increase blood flow to ischemic areas can be added to the treatment program to improve a patient’s heart function. The general term for these procedures is coronary revascularization, which is commonly performed throughout the United States.

Coronary revascularization should be considered for patients who still have debilitating angina after optimal medical therapy. The two types of coronary revascularization procedures are percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) and coronary artery bypass grafts (CABG).

- PCI is usually indicated for patients with significant narrowing of one or two major coronary arteries when the left ventricle is functioning normally.

- CABG is indicated for patients with more than two arterial constrictions, left main coronary artery disease, failed medical management, possible diabetes, or poor candidacy for a PCI, such as a long obstruction or one that is hard to access. A CABG is also considered when the patient has had a failed PCI and is still having chest pain.

There are other therapies for patients whose medical treatment does not improve the symptoms of their coronary artery disease but who are not good candidates for either PCI or CABG. The alternatives include laser transmyocardial revascularization that uses a high-energy laser to create channels in the myocardium to allow alternative blood flow to ischemic tissue (Lewis et al., 2020).

In external enhanced counterpulsation, cuffs are applied to the legs and inflated sequentially distally to proximally during early diastole, with deflation at the onset of systole. This creates a retrograde aortic flow, causing diastolic augmentation and resulting in increased coronary perfusion, increased venous return, and improved cardiac output (Lewis et al., 2020).

PERCUTANEOUS CORONARY INTERVENTION (PCI)

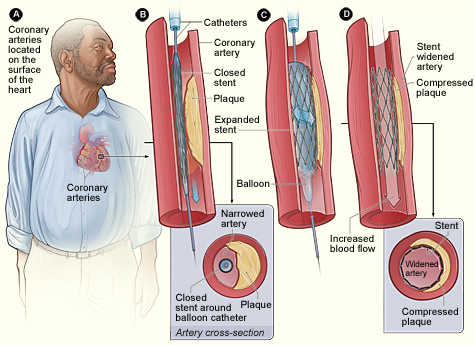

PCI, also commonly known as coronary angioplasty or simply angioplasty, is used to unclog blocked coronary arteries. If PCI is recommended, the patient may be transferred to an interventional radiology suite or cardiac catheterization laboratory, where the procedure takes place. The procedure involves threading a catheter into the constricted region of a coronary artery and expanding a tiny balloon to flatten the plaque back against the walls of the artery, creating a larger opening to improve blood flow.

A metal stent is left in the region of the flattened plaque to hold the artery open. The stent is coated with medications that are slowly and continuously released into the artery. These are called drug-eluting stents. The drugs help prevent the artery from becoming blocked with scar tissue that can form in the artery and to prevent blood clots or further plaque build-up from forming around the stent (Lewis et al., 2020).

Typically, the PCI catheter is inserted under local anesthesia using X-ray fluoroscopy. The PCI catheter is threaded through the femoral artery into the heart to the area where the coronary artery is narrowed. The procedure can take between 30 minutes and 2 hours.

PCI gives a sufficient increase in blood flow to initially reduce angina in >95% of cases. Approximately one fifth of treated arteries narrow again within 6 months, and angina returns within 6 months in about 1 in 10 patients.

In-stent restenosis (narrowing) is a continued concern with coronary angioplasty. Recent studies have shown that using drug-eluting balloon angioplasty to reopen a blocked stent is currently the most effective method for preventing the need for another reperfusion procedure.

In PCI, a catheter is threaded into the region of the artery that is narrowed by plaque. A balloon near the tip of the catheter is inflated, flattening the plaque against the arterial wall and widening the space inside the artery. A wire support (stent) is left in place to hold the artery open. (Source: NHLBI.)

Care of a patient during and after PCI includes primary nursing assessments and measures as follows:

- Perform assessment and compare to baseline: vital signs; pulse oximetry; heart and breath sounds; neurovascular assessment of extremity used for procedure; assessment of catheter insertion site for hematoma, bleeding, and bruit.

- Assess neurovascular status of involved extremity every 15 minutes for the first hour, then according to institutional policy.

- Check for bleeding at catheter insertion site every 15 minutes for the first hour, then according to institutional policy.

- Report changes in neurovascular status of involved extremity or any bleeding.

- Monitor ECG for dysrhythmias or other changes (e.g., ST segment elevation or depression).

- Monitor patient for chest pain and other sources of pain or discomfort (e.g., back, vascular access site).

- Monitor IV infusions of antianginals (e.g., nitroglycerin) and antiplatelet medications (e.g., eptifibatide).

- Teach patient and caregiver about discharge drugs (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel, lipid-lowering drugs).

- Teach patient and caregiver about discharge care, including signs and symptoms to report to HCP (e.g., access site complications, return of chest pain).

(Lewis et al., 2020)

CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS GRAFT (CABG)

Coronary artery bypass surgery is the most common open-heart operation performed in the United States, with over 500,000 procedures performed each year. CABG may be contraindicated in elderly patients and patients with end-stage kidney disease, lung disease, and peripheral vascular disease, as they are at higher risk for complications.

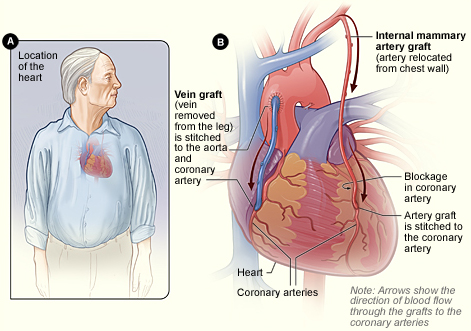

The procedure involves attaching an unclogged blood vessel to a blocked coronary artery beyond the obstruction. One or both internal thoracic (also called internal mammary) arteries can be rerouted, or a piece of the saphenous vein or the radial artery can be made into a conduit.

The surgery is done under general anesthesia and takes between 3 to 6 hours. Usually, the procedure is done by temporarily stopping the heart and oxygenating the blood with a cardiopulmonary bypass machine. When patients have no other serious disease, there is <1% mortality from a first-time CABG surgery.

In CABG revascularization surgery, blood is routed past blockages in coronary arteries. Figure B shows how vein and artery bypass grafts are attached to the heart. (Source: NHLBI.)

There are several types of bypass surgery: conventional (arrested heart) CABG, “beating heart” or off-pump CABG, minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass (MIDCAB), and robotic or totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass (TECAB).

Conventional Coronary Artery Bypass Graft

Conventional (or “on-pump”) CABG is performed on an arrested (stopped) heart through a midsternal, longitudinal incision down the patient’s chest. The patient’s heart is stopped with medications, and blood is routed to a heart-lung bypass machine, which removes CO2 and supplies oxygen, thus bypassing the processes carried out by the heart and lungs. The reoxygenated blood is returned to the body.

The procedure involves the revascularization of ischemic myocardial tissue by implanting one or both saphenous veins, a radial artery, or a mammary artery on both sides of a seriously blocked coronary artery, bypassing the blockage to provide a new source of blood flow to the previously deprived cardiac tissue. Use of the internal mammary artery has a better history of long-term patency than saphenous veins and is usually used for left anterior descending artery bypass. The radial artery is more patent than the saphenous veins but is prone to spasms unless calcium channel blockers or long-acting nitrates are given (Lewis et al., 2020).

When saphenous veins are used, it is necessary to reverse them before implantation so that the valves do not impede blood flow.

After the bypass is performed, the patient is gradually taken off the bypass pump. Pacemaker wires and chest and mediastinal tubes are inserted. The patient’s incision is then closed with a spiral suturing technique.

A conventional CABG is done for patients who have the following conditions:

- Left main coronary occlusion >50%

- At least three vessel CAD

- Advanced CAD

- Diabetes mellitus

- Refractory angina pectoris

- Heart failure associated with ischemic coronary disease

- Lesions not amenable to PCI

- Failed PCI

The patient may need blood transfusions (donor blood, blood harvested during the procedure and returned to the patient, or self-donations made in advance of surgery) to replenish blood volume, red blood cells, or platelets. Blood drained from the chest tubes postoperatively may be harvested, filtered, and transfused back into the patient. To reduce oxygen demand, the patient is placed in therapeutic hypothermia.

“Beating Heart” / Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass

In “beating heart” or off-pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) surgery, the heart is not stopped, the heart-lung bypass machine is not used, and the patient remains at normal or only slightly lowered temperature. The surgery is performed while the heart is still beating by placing mechanical stabilizers on the heart. The surgical procedure of using an internal mammary artery or saphenous veins to divert blood flow to the myocardium is identical to the traditional CABG with a bypass pump. The operating time is shorter, and the procedure is associated with fewer adverse postoperative outcomes, such as:

- Less blood loss

- Less renal dysfunction

- Less postoperative atrial fibrillation

- Fewer neurological complications

- Less incidence of stroke

- Less evidence of infection

Indications for this type of surgery include patients who have diabetes, lung disease, kidney disease, a previous history of stroke, or any other comorbidities that would put the cardiac patient at higher risk for surgery on a heart-lung or cardiopulmonary bypass pump. Fewer than 20% of patients undergoing CABG receive OPCAB surgery. Early studies showed somewhat higher mortality and the need for the proposed patients to have coronary artery lesions with no greater than 50% obstruction.

Beating heart surgery often allows patients to be discharged from the hospital more quickly than with conventional CABG, and the avoidance of the heart-lung machine has been shown to reduce the need for transfusions (Lewis et al., 2020).

Minimally Invasive Direct Coronary Artery Bypass

A MIDCAB procedure is used to bypass either the left anterior descending artery or the right coronary artery. Unlike traditional CABG, MIDCAB does not require a sternotomy or the use of a CPB pump. Instead of a long, midsternal incision, a MIDCAB includes several small incisions between the ribs or a mini-thoracotomy. The surgeon then inserts a small camera via a thoracoscope or small robotic arms through the incisions. During the procedure, the surgeon sits at a console and controls the robotic instruments to perform the CABG.

The robotic assistance is used to dissect the left internal mammary artery and separate it from the chest. Using a mechanical stabilizer at the operative site, the left internal mammary artery is sutured to the blocked artery and bypasses the blockage, providing improved blood flow to the myocardium.

Robotic arms have been in use for this type of surgery for approximately 18 years. Da Vinci was the first company that built robotic arms and made them available for surgery; they remain the brand most commonly used for robotic surgery.

The mini-thoracotomy and totally endoscopic port-only approaches to perform this type of CABG reduce surgical trauma while providing cosmetic benefits and preserve chest wall, muscle, and function. The robotic approach has been shown to improve postoperative outcomes for patients, including less pain, a positive reduction of the recovery period, and a more rapid return to full activity for the patient (Lewis et al., 2020).

This procedure is not indicated for everyone and requires specialized training for the surgeon.

Totally Endoscopic Coronary Artery Bypass

A TECAB is another type of CABG surgery done without the use of a CPB pump, or with the pump using a femoral vein approach. It is used for limited bypass grafting, usually only one coronary artery. With no incision or sternotomy, the TECAB has a much lower incidence of adverse postoperative outcomes such as infection, blood loss, pain, and recovery time. The patient typically requires a much shorter hospital stay.

Transmyocardial Laser Revascularization

A transmyocardial laser revascularization is an indirect method of revascularization. It is used for patients with advanced CAD who are not good candidates for a more traditional CABG surgery and who have persistent, significant angina despite all other medical therapy having been attempted. The procedure uses a high-energy laser to create channels in the heart muscle to allow blood flow to ischemic areas. The procedure is generally done using left thoracotomy surgery. It can be used as an adjunctive therapy when bypass grafts cannot be placed to help reduce angina symptoms (Lewis et al., 2020).

Postoperative Care and Management

Care of the patient in the postoperative setting includes collaboration and a team approach. Team members may include respiratory therapists, nurses, a cardiologist, a cardiothoracic surgeon, an anesthesiologist, and rehabilitation specialists.

Postoperative care after a CABG is as follows:

- Transfer patient immediately to the ICU. The nurse-to-patient ratio is 1:1 in at least the first 24–36 hours postoperatively.

- Attach the patient to a cardiac monitor, a mechanical ventilator connected to an endotracheal tube, a temporary pacemaker with transthoracic wires, a pulmonary artery or Swan-Ganz catheter, an arterial line in the radial artery, a mediastinal and a pleural chest tube connected to drainage containers connected to wall suction (one container for each chest tube), an indwelling (Foley) catheter, a nasogastric tube, and one or two intravenous (IV) lines.

- Monitor vital signs, watching for signs of hemodynamic changes such as severe hypotension, decreased cardiac output, and shock.

- Administer IV fluids rapidly and vasopressive agents intravenously in the case of severe hypotension.

- Initiate warming procedures according to hospital protocol.

- Assess and record vital signs every 5 minutes (if unstable) to 15 minutes until the patient’s condition is completely stable.

- Administer medications as ordered and titrate according to patient response.

- Monitor ECG for any heart rate changes or dysrhythmias.

- Evaluate and assess the patient’s peripheral pulses, capillary refill time, and skin temperature.

- Auscultate heart sounds, noting and reporting any changes.

- Monitor chest tube drainage including color, odor, consistency, and negative pressure. Observe chest tubes and drainage systems for patency, change collection chambers when appropriate, and assist surgeon with chest tube removal, 2 to 3 days postoperatively.

- Assess breathing and breath sounds, monitor ventilator settings, and check arterial blood gas (ABG) results every two hours. Suction the endotracheal tube for secretions when necessary. Assist anesthesiologist or respiratory therapist with extubation when the patient is ready.

- Monitor mean arterial pressure (MAP), pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), central venous pressure (CVP), continuous arterial pressure, and cardiac output as ordered. Once hemodynamically stable, the PAP, CVP, and arterial line will be removed, and the patient will be transferred to a step-down unit.

- Measure intake and output (I & O) and assess for any electrolyte imbalances.

- Assess the patient’s pain and provide pain medications as needed.

- Monitor the patient for signs and symptoms of stroke, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, and impaired renal function.

- Encourage incentive spirometry, coughing, and deep breathing (while splinting the incision) after the patient is weaned from the ventilator. The patient is usually extubated 6 hours postoperatively and can then be transferred to a step-down unit if hemodynamically stable.

- Reinforce or change surgical dressing when indicated, noting color, odor, consistency, and amount of drainage.

- Assist with range-of-motion exercises to enhance peripheral circulation and prevent formation of thrombus.

- Assist with ambulation per postoperative protocol. This will be initiated after the patient is extubated but before the chest tubes or any other tubes are removed.

- Provide information and emotional support to the patient and family or friends.

(Lewis et al., 2020)

COMPLICATIONS IN THE ACUTE POSTOPERATIVE PERIOD

Adverse events can occur in the postoperative period. It is important for nurses to assess the patient for postoperative complications, which may include hypothermia, atrial fibrillation or other dysrhythmias, stroke, cognitive decline (including delirium), surgical site infections, depression, and acute renal failure that may persist long after the patient has been stabilized after surgery. Traditional CABG is associated with the most complications largely due to the prolonged time spent on the cardiopulmonary bypass pump and the cooling of the blood while on the pump.

Surgical Site Infection

Surgical site infections are the most common postoperative complication in CABG patients. Risk of deep sternal wound infections is increased if a patient has a history of diabetes, smoking, obesity, and COPD. Infection rates and a risk for sepsis also increase with the use of blood transfusions, prolonged intubation, and surgical re-exploration. Careful nursing assessment for any signs or symptoms of infection includes monitoring patient temperature, pain, swelling, and incision site redness/discharge (Lewis et al., 2020).

Atrial Fibrillation

Postoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common post-CABG dysrhythmia, occurring in 20%–40% of all CABG patients. Factors that may increase a patient’s risk include peripheral artery disease, COPD, valvular heart disease, previous cardiac surgery, male gender, and advanced age. First-line treatment includes beta blockers and amiodarone. It is highly recommended that the beta blockers be started or restarted as soon as possible after surgery. A prolonged episode of atrial fibrillation will lengthen the hospital stay, especially if the patient is on warfarin for the atrial fibrillation. If the atrial fibrillation is determined to be chronic, it will be necessary to start the patient on a carefully monitored regimen of anticoagulation for the rest of her/his life (Lewis et el., 2020).

Stroke

Postoperative stroke can occur, usually in elderly patients. Risk factors include age, previous stroke, diabetes, hypertension, and female gender. Along with vital signs, nursing assessment includes postoperative neuro status checks in addition to any functional or cognitive changes that may be due to sudden stroke (Haider et al., 2018).

Preventative measures include early and progressive ambulation, sequential compression devices applied to the lower legs, and scrupulous care of needle or IV or arterial line insertion sites in order to reduce the risk of a deep vein thrombosis that could cause a stroke if it became dislodged and circulated.

Cognitive Decline

Postoperative delirium and cognitive decline may occur in a small number of patients who have undergone a CABG. The patient may experience memory impairment, difficulty concentrating, poor language comprehension, and decreased social integration. Nursing assessment includes monitoring for any cognitive changes, especially in patients at high risk. Risk factors for cognitive decline include preexisting cerebral vascular disease, central nervous system disorders, and cognitive impairment (Lewis et al., 2020).

Depression

Postoperative depression following CABG is common and can occur weeks after discharge. Symptoms of anxiety and depression peak before any heart surgery and again two weeks after and may persist up to four months after discharge. Pain, fatigue, and sleep disorders are common after a CABG and may be partly due to the lack of postoperative physical activity. Cardiac rehabilitation is highly recommended.

Depression is strongly linked to patients with low physical activity and limited mobility. Thus, it is important to initiate physical activity and rehabilitation as soon as possible following a cardiac event. Nurses should place an emphasis on educating patients and their families about the development of depressive symptoms and provide resources and strategies to address depression.

SYMPTOMS OF DEPRESSION

- Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- Feelings of hopelessness or pessimism

- Irritability

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

- Loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities

- Decreased energy or fatigue

- Moving or talking more slowly

- Feeling restless or having trouble sitting still

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions

- Difficulty sleeping, early-morning awakening, or oversleeping

- Appetite and/or weight changes

- Thoughts of death or suicide, or suicide attempts

- Aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems without a clear physical cause and/or that do not ease with treatment

(NIMH, 2018)

CASE

Mrs. Crawford is a patient on the cardiac unit who is recovering from coronary artery bypass surgery. She is 72 years old, with a daughter and son who live in the local area. Her family has been to visit throughout her hospitalization. Mrs. Crawford’s husband died two years ago from lung cancer.

Fatima is her nurse today and is preparing Mrs. Crawford for discharge in 1 to 2 days. Fatima is going over the discharge plans and reviewing all of Mrs. Crawford’s instructions and medications. Fatima also reviews Mrs. Crawford’s exercise program and verifies her appointments to see a physical therapist to continue her cardiac rehabilitation program.

As Fatima discusses the transition to the home environment, Mrs. Crawford states, “It’s pretty lonesome around the house with my husband gone. My daughter stops by when she can, but she is busy with her work, so she does not have much time.” Mrs. Crawford has not progressed as well as expected with her physical activity level in the hospital. Fatima is concerned that Mrs. Crawford may not do well with recovery if she does not progress with her exercise program. She is also concerned that Mrs. Crawford may be depressed.

In order to understand more about how Mrs. Crawford is coping, Fatima asks a couple of questions to assess depressive symptoms. Fatima asks Mrs. Crawford about her sleep habits, social contacts, and hobbies. When asked directly, “Do you feel like you are ‘blue’ or depressed after this heart surgery?” Mrs. Brown starts to cry. She says, “I just am not sure if I want to go home alone. I am afraid, and I have no one to be with me. I miss my husband.”

With this feedback, Fatima discusses her assessment with the cardiologist in charge of Mrs. Crawford’s care in the hospital. Mrs. Crawford is started on Zoloft therapy (an SSRI, which is safe to take with her cardiac meds). Fatima reviews with Mrs. Crawford and her family members which depressive symptoms they should be aware of. Fatima also reiterates how important it will be to continue her rehabilitation program because exercise and physical activity may potentially lift her spirits. Fatima also encourages Mrs. Crawford to be in close contact with friends, which will give her the opportunity to get out of the house and be with others.

Mrs. Crawford seems to understand the importance of following her rehabilitation plan. Fatima confirms her follow-up appointment in one week with the team. Mrs. Crawford and her family verbalize understanding of the discharge plans.

Acute Renal Failure

Incidence of acute renal failure after CABG is up to 30%, which is a greater mortality rate while still hospitalized than in post-CABG patients with no renal injury. A small percentage (approximately 2%) of patients will go on to need dialysis, possibly temporarily.

One large, retroactive propensity score-matching study compared 466 pairs of individuals over 70 years old. Half underwent CABG surgery on a cardiac bypass pump and half did not use the pump. It was found that 40% of all patients experienced acute kidney injury (AKI), primarily only stage 1, but the use of the bypass pump did not determine kidney failure (Wang et al., 2020).

Some risk factors for renal failure post-CABG are not modifiable, such as advanced age, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and peripheral vascular disease. Other factors are specific to anesthetic, high-volume blood transfusion, aortic cross-clamping, and ICU management.

Careful nursing monitoring includes kidney function (urinary output, creatinine clearance, and other kidney function tests), especially for those patients at high risk, including those with preexisting renal dysfunction, decreased cardiac output, insulin-dependent diabetes, peripheral artery disease, advanced age, African race, and female gender.

Complications in Older Adults

Older adults, including those over age 80, tolerate elective CABG fairly well. The incidence of postoperative complications is higher than in younger patients, possibly because of a larger number of comorbidities. These complications may include dysrhythmias, stroke, postoperative cognitive dysfunction, and infection. Despite the increased incidence of complications, the benefits of the surgery typically outweigh the risks (Lewis et al., 2020).

POSTOPERATIVE PHYSICAL AND OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

Frequently, a patient with physical limitations following a cardiac event will be referred to a rehabilitation specialist. Based on the assessment and evaluation, the physical and/or occupational therapist creates an individualized treatment plan that includes the patient’s goals for treatment and addresses their physical limitations. Research studies suggest that nonpharmacologic interventions such as exercise training and psychoeducation have a positive physiologic and psychological effect in early outpatient rehabilitation.

Physical Therapy

The primary outcome goal in post-CABG cardiac rehabilitation is physical function. This can be measured by the 6-Minute Walk Test, which assesses functional, aerobic capacity as indicated by heart rate, blood pressure, and a self-evaluated Borg rate of perceived exertion (RPE). The secondary outcomes are mental health and increased physical activity that will be encouraged and continued when the patient is discharged from the hospital.

Early and frequent physical therapy, starting as soon as one day after surgery, can help restore a normal pattern of daily functioning in a patient post-CABG. A customized physical therapy program may include exercises for range of motion, muscle strengthening, and coordination. Exercises will vary depending on the patient’s baseline condition (Sears, 2019).

INITIAL PHYSICAL THERAPY EVALUATION

Patients who are stable after a cardiac event will have an initial evaluation while recovering in the hospital. Elements of a physical therapy evaluation include:

- Medical history

- Heart rate

- Blood pressure

- Oxygen saturation

- Upper body strength and range of motion

- Lower body strength and range of motion

- Level of functional mobility and ability to perform self-care

- ECG measurements at rest and during activity

- Other measurements of baseline functional status (e.g., Timed Up-and-Go [TUG] Test or 6-Minute Walk Test)

Exercise is a key component of physical rehabilitation and focuses on maintaining and improving strength, endurance, balance, and overall functional mobility. When the postoperative patient can tolerate it and has had most tubes removed, exercise may include, but is not limited to, walking with the help of parallel bars, using a treadmill that can be adjusted to include an inclined surface, or riding a stationary bicycle. When patients tolerate these exercises well, they may progress to stair-climbing on a wooden platform containing two or three steps.

These exercises will be done while the patient is connected to a cardiac monitor to observe stress-induced dysrhythmias. Should they occur, the exercises will immediately be stopped and the patient returned to his/her room. Additionally, if dyspnea, dizziness, or chest pain occurs during exercise, the exercise is stopped immediately and the patient’s cardiac status reassessed. Before hospital discharge, patients are reassessed so that an individual home exercise program can be taught to the patient and any caregivers (Portugal, 2021a).

(See also “Cardiac Rehabilitation Phases” below).

Occupational Therapy

Occupational therapists have specialized knowledge and skills that address the limitations that patients may experience with the performance of basic activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Driving, for example, is particularly complex, requiring an integration of visual, physical, and cognitive tasks (Portugal, 2021b). After a CABG, the physician usually informs the patient when it is safe to begin driving again. This period may extend 6 weeks or more postoperatively depending on the patient’s surgical wound healing and pain level.

COMMON ACTIVITIES EVALUATED DURING POSTOPERATIVE RECOVERY

ADLs:

- Eating

- Dressing

- Bathing

- Grooming

- Toileting

- Transfers (such as moving between the bed, chair, and bathtub or shower)

IADLs (require more complex cognitive functioning):

- Preparing meals

- Telephone calling

- Writing

- Working on a computer

- Managing finances

- Following a daily drug regimen accurately

- Cleaning, doing laundry

- Grocery shopping and other errands

- Traveling as a pedestrian or by public transportation

- Driving

The occupational therapy process begins with a thorough evaluation that identifies the baseline status of the patient and any secondary disabilities, the need for any assistive devices, home safety, and any areas of the patient’s occupation or skills that may be difficult for the patient to perform. Patients are evaluated for any limitations that require intervention and for any strengths that can be used to compensate for weaknesses. Limitations may involve motor function, sensation, cognition, or psychosocial function. Evaluators determine the activities (e.g., ADLs, work responsibilities, leisure activities, social integration, or learning and comprehension) for which patients want or need help.

Before developing a cardiac rehabilitation program, an occupational therapist observes patients doing each activity of the daily routine to learn what is needed to ensure safe, successful completion of the activities, with methodologies that are intended to become progressively more complex and challenging. Therapists can then recommend ways to eliminate or reduce maladaptive patterns and to establish routines that promote function and health. Specific performance-oriented exercises are also recommended. Therapists emphasize that exercises must be practiced and motivate patients to do so by focusing on exercise as a means of becoming more active at home and in the community.

Patients who are planning to return to a work environment may need to adjust their work schedules and place limits on physical activities (such as lifting) depending on the type of work in which they are engaged. Patients are taught creative ways to facilitate social integration activities (e.g., how to get to a museum, movie theater, or church without driving). They are also given instructions about how to use hearing aids or other assistive communication devices in different settings. Important strategies may include how to travel safely with or without a cane or walker. Therapists may suggest new activities such as volunteering in foster grandparent or mentoring programs, in schools, in libraries, or at hospitals. Patients are taught strategies to compensate for their limitations, such as to sit when gardening or showering. The therapist may identify various assistive devices that can help patients do many activities of daily living (Portugal, 2021b).

STERNAL PRECAUTIONS

Sternal precautions will help the patient recover from a sternal incision and prevent separation of the breastbone as it heals. These precautions should be followed by the patient for four to six weeks until the sternal incision is well healed.

Patients should be instructed on the following precautions:

- No pushing or pulling with the arms

- Limit lifting, pushing, or pulling to 5 to 10 pounds

- No reaching of arms directly over the head

- No extension of both arms out to the side

- No reaching with the arms to the back or above shoulder height

- No driving for 6 to 8 weeks

Physical and occupational therapy strategies to assist the patient in protecting the sternum include instructions on the following:

- Scooting in when rising from a chair

- Using the leg muscles when moving from sitting to a standing position

- Walking up stairs without pulling on the rail

- Rolling in bed and gradually sitting up without using the arms

- Using assistive devices if recommended (e.g., walker or quad cane)

- Holding a heart pillow during transfers to avoid putting pressure on the arms

- Holding the heart pillow tightly to the chest during laughing, sneezing, or laughing to “splint” the incision like a broken bone

- Strategies to assist the patient in performing ADLs such as bathing, dressing, and brushing hair

- Performing arm exercises with weights: one arm at a time to prevent pressure on the sternum, no more than 1- to 2-pound weights, no higher than shoulder level

(UHN, 2018)

POSTOPERATIVE CARDIAC REHABILITATION GOALS

Studies show it is in the best interests of CABG patients to undergo active exercises and strengthening in order to help prevent postoperative complications and enable the patient to return home more quickly. Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is universally recognized as a means to promote decreased mortality, morbidity, and disability, and increased quality of life in all cardiac patients, including after surgery. Despite the proven beneficial effects of cardiac rehabilitation, participation is often less than optimal due to cost, location, and difficulties with traveling to the therapy.

There are four phases of CR. In the immediate postoperative period, phase I of cardiac rehabilitation is initiated. The interventions in phase I rehabilitation after CABG are the results of investigation in the physical or the psychological perspective. Cardiopulmonary bypass has a temporarily negative effect on the physical function level. The effect of respiratory exercise preoperatively and in the early postoperative period after CABG surgery has been examined using different techniques that are found to be very effective. CR programs are supervised and monitored by trained rehabilitation professionals. The goals of cardiac rehabilitation are to maximize strength, prevent regression of CAD, and reduce the likelihood of future cardiac problems.

Comprehensive rehabilitation programs that include exercise, education, counseling, and help with lifestyle changes can:

- Increase exercise tolerance

- Decrease symptoms (such as angina and shortness of breath)

- Improve blood lipid levels

- Reduce stress

- Make it easier to stop smoking

- Improve mood

Many patients with CAD who are over 60 and have had a heart attack or heart surgery may understandably be fearful of exercise. They are likely to have deficits in muscle strength and balance.

The first step in reassuring patients is to educate them about the disease in general and their condition. General advice should include a review of the symptoms of ischemia, rules on managing an episode of angina or dyspnea, and an explanation of what symptoms require a quick trip to an ED. The patient’s family should be included when educating the patient.

Patients with signs and symptoms of depression are less likely to complete their cardiac rehabilitation programs, and it is important to identify these patients and to get the appropriate help for them early in the program.

Rehabilitation specialists are involved in advising patients on resuming their normal activities after discharge from the hospital. Recommendations may include:

- Daily walking can be encouraged immediately.

- Sternal precautions may be recommended (see above).

- Patients can often resume their previous level of sexual activity in 2 to 4 weeks, depending on their tolerance for exercise. (If patients have no symptoms of angina, dyspnea, or palpitations with moderate-exertion physical activity, this is a good indication that they will not have symptoms during sexual intercourse.)

- Routine driving can usually be resumed in 2 to 4 weeks in those states that allow it. Some states consider a postoperative CABG to be a disqualifying condition and require that a cardiologist approve fitness for driving.

- Patients can return to work with recommended modifications to their schedule or duties as needed.

(Lewis et al., 2020; Portugal, 2021b)

(See also “Cardiac Rehabilitation” below.)

CASE

John Townsend, age 65, is recovering in the hospital from CABG surgery to reopen a blocked coronary artery. The day after his surgery he is visited by a nurse and a physical therapist, who each brief him on the cardiac rehabilitation regimen he is about to undergo. John expresses anxiety about having to undergo cardiac rehabilitation so soon, but the nurse and physical therapist reassure him that the regimen will be helpful and manageable and that it will start slowly.

John starts his early-stage (phase I) cardiac rehabilitation the next day. On performing an initial evaluation of John’s functional mobility status and activity tolerance, the physical therapist helps to teach him how to transfer from the bed to the chair without causing physical stress to his incision or using his arms. Later, the physical therapist helps John to get out of bed and walk a short distance to the door of his room and back again. That exercise is repeated twice more the same day. The therapist talks to John about his plan for home ambulation following discharge.

The nurse introduces John to the occupational therapist, who helps John begin taking care of his ADLs, such as personal care, bathing, eating, and understanding the timing and administration of new medications. The occupational therapist addresses planning for his transition to the home environment by asking John about safety issues, anticipated barriers in the home, and assistive devices needed or used in the past. Together, they plan for strategies to address showering at home.

The next day, after his physical therapist has determined the level of assistance needed for John to ambulate safely, the nurse helps him venture out to the corridor, and he is able to walk slowly to the nurses’ station, which is 60 feet from his room. John takes two more corridor walks that day and four such walks each of the next two days.

By the time he is discharged on day five post surgery, John can walk in the hallway for 10 minutes at a time. The nurse reinforces the safety recommendation instructions from the physical therapist and reviews the detailed instructions with John on continuing with his exercise plan while at home. The nurse has John repeat back to him how he will adapt his ADLs to accommodate his temporary restrictions and his plans to work toward and improve his preoperative level of function.

John has support at home from his wife, and the nurse schedules a home health visit twice a week for one month to monitor his progress. John is also scheduled to see his doctor and the physical therapist for a follow-up visit in one week to start his long-term outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program.

DISCHARGE PLANNING AND EDUCATION

Discharge planning following a cardiac event or procedure may include the following patient education and instructions:

- Monitor for signs of infection (redness, swelling, discharge, drainage, fever, or sore throat).

- Recognize the symptoms to be reported.

- Know how to take care of any dressings or incisions, including what to do to protect the operative site during bathing/showering.

- Understand the warning signs for arterial reocclusion (angina, dizziness, dyspnea, rapid or irregular pulse, and shortness of breath).

- Monitor body weight and notify the primary care provider of any weight gain of more than 3 lbs (1.4 kg) in one week.

- Follow any special dietary instructions (especially any sodium and cholesterol restrictions).

- Restrict any lifting to <10 lbs. for 4 to 6 weeks.

- Maintain a good sleep routine, with at least 8 hours of sleep each night and short rest periods throughout the day.

- Participate in an exercise program and cardiac rehabilitation recommendations, including specific restrictions and when activities can be resumed.

- Follow any lifestyle modifications recommended (smoking cessation, nutrition, and exercise programs).

- Understand the dose, indication, frequency, and side effects of all prescribed medications.

- Understand the follow-up plan of care, including visits with cardiology, the surgeon, and the primary care provider.

(Lewis et al., 2020)