ASTHMA PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiology of asthma is complex and involves:

- Airway inflammation

- Airway hyperresponsiveness

- Intermittent airflow obstruction

- Airway remodeling

The important role of inflammation has been substantiated, but evidence is emerging for considerable variability in the pattern of inflammation, indicating differences in phenotype, which may have a significant influence on responses to treatment.

The mechanism of inflammation may be either acute, subacute, or chronic, and the presence of airway edema and mucus secretion contributes to airflow obstruction and bronchial reactivity. Varying degrees of mononuclear cell and eosinophil infiltration, mucus hypersecretion, desquamation of the epithelium, smooth muscle hyperplasia, and airway remodeling are present.

Airway hyperresponsiveness is an exaggerated response to numerous exogenous and endogenous stimuli. The mechanisms involved include direct stimulation of airway smooth muscle and indirect stimulation by substances from mediator-secreting cells such as mast cells or nonmyelinated sensory neurons.

The progression of the underlying disease severity does not appear to be prevented by current asthma treatment with anti-inflammatory medications (Morris, 2020).

During an asthma attack, the airways of the lung narrow and the movement of air is obstructed. This narrowing is caused by three processes: muscles in the airway walls contract, the airway walls become edematous and swollen, and excess mucus fills the airways. (Source: National Institutes of Health: National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute.)

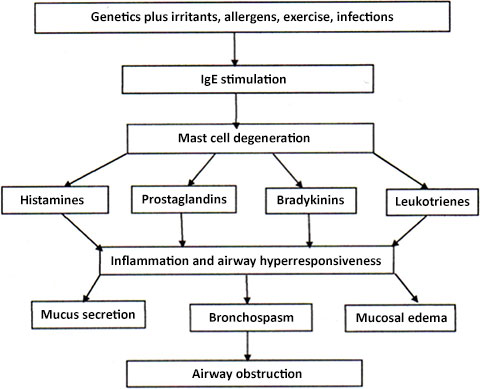

The Asthma Cascade

The asthma cascade is the well-defined constellation of signs and symptoms produced by an allergen or by other factors. Allergens are normally harmless substances that the immune system treats as health threats. When a person who has the allergic type of asthma comes into contact with one of these substances after becoming sensitized to it, the immune system responds to combat it. In patients with nonallergic asthma, when something other than an allergen (e.g., exercise, cold weather) induces asthma symptoms, the immune system responds in the same manner.

Within minutes following such an exposure, the person has a reaction caused by the release of mast cells, which degenerate and release histamines, prostaglandins, bradykinins, and leukotrienes. These substances affect nerve cells, smooth muscle cells, goblet cells that secrete mucus, and endothelial cells that affect blood vessels. This results in:

- Increased capillary permeability

- Mucosal edema

- Bronchoconstriction (bronchospasm)

- Thick tenacious mucus secretion

- Hyperresponsiveness of bronchial smooth muscle

- Reversible air flow obstruction

(MacNaughton, 2019)

Asthma cascade. (Source: Author.)

Over time, damage to the epithelial cells affect ciliary function, impairing the removal of mucus and cellular debris and resulting in the formation of airway plugs. In addition, long-term damage caused by repeated bouts of untreated inflammation results in airway remodeling by epithelial cells, which may worsen inflammation and aggravate asthma over time if not treated and managed correctly.

Irreversible airway obstruction may develop in some patients with asthma who have moderate to severe asthma, which leads to poor prognosis and is highly associated with smoking and male gender. In these patients, the structure and function of the airway changes cannot be reversed in spite of ongoing anti-inflammatory or bronchodilator treatment (Boulet et al., 2020).

Asthma Development in Children and Adolescents

Asthma usually develops in children before the age of 5 years. Many children who have allergies develop asthma, but not all.

Usually, symptoms begin in the first years of life. It has been found that about 25 out of 100 children with persistent asthma began wheezing before they were 6 months old, and about 75 out of 100 began wheezing by the age of 3 years. As a child grows, approximately:

- 15 out of 100 infants who wheeze develop persistent wheezing and go on to develop asthma.

- 60 out of 100 infants who wheeze no longer wheeze by age 6.

- 50 out of 100 preschool-age children who wheeze have persistent asthma later in childhood.

In most cases of intermittent asthma associated with respiratory infections (rather than allergies), symptoms tend to become less severe and may disappear by adolescence. But asthma seems to continue in adolescence in children who have moderate to severe asthma, and these children may have asthma as adults.

Children with persistent asthma:

- Developed symptoms before age 3

- Had allergies in infancy and childhood

- Have a family history of allergies

- Wheeze without a viral infection present

- Have recurrent asthma attacks associated with viral infections (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus)

- Have been exposed to tobacco smoke including before birth

Other risk factors that increase a child’s likelihood of developing asthma include:

- Living in an area with high pollution

- Obesity

- Being male

- Being Black or Puerto Rican

(UM, 2020; Mayo Clinic, 2021a)

Asthma Development in Adults

Asthma can develop at any point in life. When people are diagnosed with asthma when they are older than age 20, it is known as adult-onset asthma. New-onset asthma in adults is often the result of undiagnosed childhood asthma. However, some people who had childhood asthma tend to experience reappearance of symptoms through their 30s and 40s at various levels of severity.

Unlike children who often have experienced intermittent asthma symptoms in response to allergy triggers or respiratory infections, adults with newly diagnosed asthma generally have persistent symptoms, and daily medications may be required to keep their asthma under control.

There are several factors that make a person more likely to develop adult-onset asthma. Being a woman increases the risk after age 20, and obesity appears to significantly increase the risk. Individuals who had asthma as a child may see asthma recur later in life.

At least 30% of adult asthma cases are triggered by allergies, especially those who are allergic to cats. Exposure to allergens or irritants such as cigarette smoke, chemicals, mold, dust, or other substances commonly found in the person’s environment, including home or work, may trigger the first asthma symptoms, and prolonged exposure to certain occupational workplace materials may set off asthma symptoms in adults.

Hormonal fluctuations in women may play a role in the development of adult-onset asthma, and some women first develop asthma symptoms during or after pregnancy. Women going through menopause can also develop asthma symptoms for the first time.

Different illnesses, viruses, or infections can be a factor in the development of adult-onset asthma, and a serious cold or bout with influenza is often a factor. Smoking is not a cause of adult-onset asthma; however, smoking or being exposed to secondhand smoke may provoke asthma symptoms (AAFA, 2021c).

Asthma Development in Older Adults

Asthma can develop in anyone at any age, and it is not uncommon for adults in their 70s or 80s to develop asthma symptoms for the first time. The most common triggers for the appearance of asthma include respiratory infections or virus, exercise, allergens, and air pollution. Up to half of older people with an asthma diagnosis are current or former smokers. Tobacco smoke damages the airways, which then respond with asthma symptoms, and contributes to worsened control of symptoms (AAFA, 2021d).