MANAGEMENT OF ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS (ATTACKS)

The most effective strategy for dealing with an asthma attack is early recognition and treatment. In ideal situations, patients assess the severity of an asthma attack at home by following an individualized asthma action plan (see “Developing an Asthma Action Plan” later in this course).

Some patients are more sensitive to an increase in asthma symptoms than others who may not recognize a problem until reduced airflow becomes more severe. This group may not know that asthma is worsening until a PEF measurement shows a decrease. It is helpful to identify these patients and provide education stressing that recognition of early signs of worsening asthma should be based on PEF monitoring.

Patients with a history of the following are at high risk for a fatal asthma attack:

- Previous severe exacerbation (e.g., intubation, intensive care unit admission)

- Asthma attack despite current course of oral glucocorticoids

- More than one hospitalization for asthma in the past year

- Three or more emergency department visits for asthma in the past year

- Food allergy in a patient with asthma

- Currently not using inhaled glucocorticoids

- Recent or current course of oral glucocorticoids

- Use of more than one canister of SABA per month

- Difficulty perceiving asthma symptoms or severe exacerbations

- Poor adherence with asthma medication and/or written asthma action plan

- Illicit drug use and major psychosocial problems including depression

- Comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular or chronic lung disease)

(Fanta, 2021a)

Basic Principles of Asthma Management

Basic principles of management of asthma to control hypoxia and to reverse airflow obstruction include:

- Assessing the severity of the attack and risk for asthma-related death

- Assessing potential triggers

- Using inhaled short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABAs) early and frequently

- Considering concomitant use of ipratropium for severe exacerbations

- Starting systemic glucocorticoids if there is not an immediate and marked response to the inhaled SABA

- Making frequent (every 1–2 hours) objective assessments of response to therapy until definite, sustained improvement is documented

- Advising patients who are not responding to go to an acute care facility or their asthma provider immediately, especially if they have a history of near-fatal asthmatic attacks

(Fanta, 2021a)

Initial Home Management

The goals for home management are to relieve symptoms and prevent worsening of the attack to a severe and possibly life-threatening event. Patients should follow the instructions in their asthma action plan, which may include:

- Administer SABA, 2 to 4 puffs, preferably using a spacer, 2 puffs for mild to moderate symptoms and 4 puffs for more severe symptoms, or via nebulizer.

- SABA may be repeated every 20 minutes for the first hour as needed. A mild asthma attack usually responds to 2–4 puffs every 3–4 hours.

- After the first hour, if there is improvement with SABA, based on action plan or clinician guidance, a determination about seeking additional medical attention should be made.

- If there is a good response to home treatment and repeat PEF increases to >80% of the patient’s baseline over the course of about one hour, then the patient can safely continue home treatment.

- If there is an incomplete response, the clinician should be contacted for advice and possible initiation of oral glucocorticoids according to the patient’s prednisone-based action plan.

- The single most effective strategy for reducing emergency department visits and hospitalization for acute asthma is the timely administration of oral glucocorticoids.

- If initial home treatment is unsuccessful and there are signs or symptoms of severe asthma, or if the peak flow is <50% of the patient’s baseline, urgent medical attention should be sought.

The patient should not drive themself to the urgent care setting, and inhaled SBA should continue to be used while waiting for help to arrive (Fanta, 2021a; Morris, 2020).

ASTHMA HOME MANAGEMENT FOR CHILDREN YOUNGER THAN 2 YEARS

When children or their caregivers recognize the onset of an exacerbation, an inhaled SABA should be administered using an MDI with spacer or nebulizer, 2–4 puffs of albuterol or 1.25 mg nebulized solution per dose. Symptoms should be assessed in 10–20 minutes, and if needed, the dose can be repeated. Based on the initial response, the patient should either continue self-care or seek medical attention.

If there is a good response within 4 hours, continue with home management using SABA every 4–6 hours as needed. If there is an incomplete response, start oral glucocorticoids, if available, and contact the clinical providers for advice. Timely administration of oral glucocorticoids is probably the single most effective strategy for reducing ED visits and hospitalizations.

If there is a poor response, continue administering SABA and seek immediate medical attention in the ED (Sawicki & Haver, 2020).

RESPONDING TO AN ATTACK WHEN NO INHALER IS AVAILABLE

An individual experiencing an asthma attack but who does not have a quick-relief inhaler at hand can be instructed to follow these steps:

- Get away from the asthma trigger as soon as possible and go to an air-conditioned environment or other place with clean air.

- Sit upright; stooping over or lying down constricts breathing.

- Loosen clothing.

- Take long, deep breaths to help slow down breathing and prevent hyperventilation, breathing in through the nose to the count of four and then out through the mouth to the count of six. Purse the lips during exhalation to slow breathing and keep airways open longer.

- Stay calm to prevent further tightening of chest muscles and make breathing easier.

- Drink a cup or two of a hot, caffeinated beverage (coffee or black tea), which can help open the airways slightly and help loosen mucus, providing some relief for an hour or two. (Caffeine is mobilized into theophylline, which is a drug used to prevent and treat asthma by relaxing airways and decreasing the lungs’ response to irritants.)

- Seek emergency medical help if wheezing, coughing, and breathing difficulty do not subside after a period of rest.

(SingHealth, 2021)

CASE

Responding to an Asthma Attack

Gabriela, an RN, volunteers at her town’s summer concert series. The concerts are held once a month at one of the local parks, and people sit on blankets or folding chairs on a hillside overlooking the lake and stage.

Shortly after the first intermission starts, a frantic mother and teenager enter the first aid tent. The mother shouts, “My daughter Mattie needs hot coffee RIGHT NOW!” Mattie is pale, bent forward clasping her chest, struggling for breath, and obviously anxious. The mother tells the volunteers that her daughter is having an asthma attack, doesn’t have her inhaler, and that her doctor said hot black coffee could be used while waiting for an ambulance. She tells them Mattie had been exposed to cigarette smoke up on the hillside and that it’s one of her asthma triggers.

Gabriela remains with Mattie and her mother while another volunteer goes to a nearby concession stand for the coffee and a third calls 911. Mattie tells Gabriela that her chest feels tight and that she can’t breathe. Gabriela tells her to sit down and sit up straight. She talks calmly to Mattie while applying a pulse oximeter to her finger, telling her to start taking slow, deep breaths, to breathe in through her nose, and to breathe out through her mouth while pursing her lips. Mattie’s SaO2 is 95% on room air, and Gabriela tells Mattie that her “oxygen number” is within a safe range, the coffee is coming, and the ambulance will arrive shortly. Gabriela continues to talk calmly to both Mattie and her mom and notes that, as they talk, Mattie appears less anxious and her SaO2 drifts between 94% and 96%.

The hot coffee arrives and Mattie drinks it slowly but steadily, grimacing because she “hates coffee.” The ambulance arrives, and the EMTs assess Mattie, whose SaO2 is now 96% on room air. Per protocol, they administer a bronchodilator by nebulizer and monitor her response. Mattie responds well to the nebulizer treatment and meets criteria for discharge-to-home with an SaO2 of 99%.

During the entire treatment, Mattie’s mom vacillates between holding her daughter’s hand and berating herself for forgetting to bring the inhaler. One of the other volunteers stays with her and encourages her to be a bit easier on herself and try to remain calm to help Mattie relax.

As Mattie’s primary volunteer care provider, Gabriela tells Mattie, who is 17 and a high school senior, that she is not blaming either her or her mom for forgetting the inhaler but encourages her to take responsibility for making certain she has her inhaler with her at all times. She also asks if Mattie has a written asthma action plan, to which she replies yes.

When Mattie and her mother leave, they assure themselves and the volunteers that this has been a scary but valuable lesson. At the end of the concert, they stop by the tent to report that Mattie is doing fine and has had no further problems.

Asthma EMS Management

EMS management begins with assessment, which may be complicated by a setting that includes noise, distractions from bystanders or family, and an anxious hypoxic patient who is unable to provide a complete history.

It is important to determine treatment provided to the patient before EMS arrival. If the patient is having a prolonged attack that has not responded to several doses of SABA/ipratropium, epinephrine IM is administered immediately. If available, terbutaline is an acceptable substitute.

Following assessment, the primary goal in EMS treatment is reversal of bronchospasm with nebulized SABA, connected to oxygen at 6–8 LPM. Ipratropium bromide can be mixed with SABA in a nebulizer, and both can be administered until the patient’s symptoms improve. As soon as IV access is obtained, normal saline is run wide open to prevent dehydration.

CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) is a prehospital treatment option for moderate to severe asthma attacks. CPAP increases the pressure that the patient exhales against, which pushes open lower airways and improves gas exchange. Nebulized bronchodilators should be administered through CPAP, which provides an airtight seal to help direct medication into the lower airways. Care must be taken to avoid applying too much pressure, as air sacs are hyperinflated, and it is possible to cause a pneumothorax.

Magnesium sulfate intravenously over 20 minutes may also be administered for its effect as a smooth muscle relaxant.

For patients who are anxious or combative during a severe asthma attack, ketamine IV or IM is the ideal medication for sedation, as it causes bronchodilation and does not carry a risk of respiratory depression. It may help patients tolerate having an oxygen mask or CPAP applied.

Methylprednisolone or dexamethasone IV is then given to reduce inflammation. At this point, the airway is reassessed to determine if the patient is responding to the drugs or if intubation is required.

Asthma patients with impending respiratory arrest require assisted ventilation starting with a bag valve mask and may later require intubation (Gandy, 2021; Sullivan, 2021).

CAPNOGRAPHY

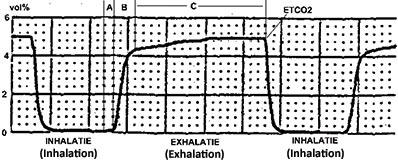

One recent addition to assist in assessment is waveform capnography. Waveform capnography is a valuable tool to differentiate an asthma attack from other causes of respiratory distress (Sullivan, 2021). Capnography is a noninvasive measurement during inspiration and expiration of the concentration of carbon dioxide in the respiratory gases. End tidal capnography (EtCO2) is the measurement of the amount of carbon dioxide at the end of an exhaled breath. The results are displayed on a screen in waveforms, and provide an immediate picture of the patient’s condition.

Capnography waveform measuring amount of exhaled carbon dioxide. (Source: Rschiedon at Dutch Wikipedia, CC SA 3.0.)

CASE

EMS Response to an Asthma Attack

EMS crew 3 is called to the home of Howard by his wife, who reports he is experiencing a severe asthma attack. When they arrive, they find Howard wheezing and extremely dyspneic. The patient’s wife tells the team he has been using his rescue inhaler multiple times over the last few hours without relief.

The crew determines Howard is nearing respiratory arrest as evidenced by his inability to speak two words in a row, severely reduced tidal volume, cool and clammy skin, and rapid heart rate and breathing.

Paramedic Jordan administers 0.5 mg IM epinephrine 1:100 IM immediately, and EMT Sharon places the patient on CPAP at 5 mmHg. Jordan starts an IV of normal saline followed by administration of 125 mg of methylprednisolone. Magnesium sulfate 2 gm IV is then started to run over 10 minutes. Capnography is used to monitor Howard’s response to treatment, which begins to show improvement, and he is then transported to the hospital emergency department.

Emergency Department Management

In an acute care setting, assessment of asthma exacerbation severity is based on symptoms, physical findings, peak expiratory flow, or less commonly, forced expiratory volume in one second measures, pulse oxygen saturation, and in certain circumstances, arterial blood gas measurement.

A focused history and physical are obtained while treatment is initiated, assessing for signs of severe exacerbation, which may include:

- Tachypnea

- Tachycardia

- Use of accessory muscles

- Diaphoresis

- Inability to speak in full sentences or phrases

- Inability to lie supine due to breathlessness

- Pulsus paradoxus

It is important to note that up to 50% of patients with severe airflow obstruction will not manifest any of these signs.

Assessment is made for symptoms such as fever or purulent sputum in order to rule out alternative diagnoses. Chest X-ray is obtained when a complicating cardiopulmonary process is suspected, when a patient requires hospitalization, and when the diagnosis is uncertain.

Pulse oximetry is obtained for noninvasive screening for hypoxia, and a peak flow measurement is made in those without signs of impending respiratory failure.

In the ED, standard treatment includes:

- Supplemental oxygen is administered for all patients with hypoxemia, usually via nasal cannula but occasionally by face mask if needed.

- Inhaled SABA is standard therapy for initial care. Typically, three treatments are administered within the first hour. Delivery method varies with the setting and severity of the attack.

- Ipratropium, an inhaled anticholinergic agent (short-acting muscarinic antagonist, or SAMA) may be added.

- Systemic glucocorticoids are essential for resolution of an exacerbation that does not respond to intensive bronchodilator therapy. Glucocorticoids speed the rate of improvement, but this is not clinically apparent until as long as six hours after administration.

- Intravenous administration of magnesium sulfate is warranted for patients presenting with a life-threatening exacerbation or who have a severe exacerbation that is not responding to initial therapy.

After the first hour of intensive treatment, a patient whose symptoms have resolved and whose PEF is 80% of predicted with good self-care skills and a supportive home environment may be discharged to continue treatment at home. Otherwise:

- Those who have an incomplete response and PEF of 60%–80% of predicted should continue intensive and close observation and treatment for approximately 1–3 more hours.

- Those who have worsening symptoms and declining PEF or pulse oxygen saturation require hospitalization and may need intensive care.

- Patients continuing treatment in the ED who have worsened or not improved after an additional 1–3 hours of frequent inhaled SABA treatments and oral glucocorticoids should continue care in an observation unit or be hospitalized.

LIFE-THREATENING ASTHMA EXACERBATION

In patients presenting to the ED with impending or actual respiratory arrest, in addition to the treatments outlined above, options for ventilatory support must be assessed and implemented immediately if needed. Signs of impending arrest that require rapid sequence intubation may include:

- Slowing of respiratory rate

- Depressed mental status

- Inability to maintain respiratory effort

- Inability to cooperate with administration of inhaled medications

- Worsening hypercapnia and associated respiratory acidosis

- Inability to maintain an oxygen saturation >92% despite face mask supplemental oxygen

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is increasingly used in patients with severe asthma exacerbations in an effort to avoid invasive mechanical ventilation. Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NPPV) using a mask that conducts gas from a positive-pressure ventilator into the airways has become the predominant means of administering NIV. A short trial of NIV may be appropriate in cooperative patients not responding to medical therapy who do not require immediate intubation (Fanta, 2021b).

WHEN TO HOSPITALIZE

The decision to admit to the hospital is based on findings from repeat assessment of a patient after receiving three doses of an inhaled bronchodilator, including the following criteria:

- Duration and severity of asthma symptoms

- Severity of airflow obstruction

- Course and severity of prior exacerbations

- Medication use and access to medications

- Adequacy of support and home conditions

- Presence of psychiatric illness

Patients who should be admitted to ICU for close observation and monitoring may exhibit the following:

- Rapidly worsening asthma or a lack of response to the initial therapy in the ED

- Confusion, drowsiness, signs of impending respiratory arrest, or loss of consciousness

- Impending respiratory arrest, as indicated by hypoxemia despite supplemental oxygen and/or hypercarbia

Intubation is required because of the continued deterioration of the patient’s condition despite aggressive treatments.

Status asthmaticus, an acute severe asthmatic episode that is resistant to appropriate outpatient therapy, is a medical emergency requiring aggressive hospital management. This may include admission to the ICU for treatment of hypoxia and dehydration, and possibly for assisted ventilation due to respiratory failure (Fanta, 2021b; Morris, 2020).

DISCHARGE FROM THE ED

Most patients with improving symptoms and a PEF >60% of predicted can be safely discharged if they are knowledgeable about their asthma and have the availability of follow-up care. Even with a rapid improvement, patients should be watched for 30–60 minutes to be certain they are stable before being released.

The patient should be discharged with oral glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone) for a period of 5–7 days. Intramuscular injection of a long-acting glucocorticoid formulation is occasionally given to patients who do not have access to oral medication or are at a high risk for medical nonadherence. Disadvantages of this route is that duration is not predictable, and cutaneous atrophy and depigmentation at the injection is possible.

Every single patient who has had an asthma attack severe enough to require emergency management should be given an inhaled glucocorticoid as part of the discharge medication plan.

Patient education includes a brief, focused session providing information about asthma, how to avoid asthma triggers, and how to provide initial home management in the event of further exacerbations. Assessment and retraining of inhaler use technique should be included. If the patient does not already have one, a personalized asthma action plan is provided.

Follow-up care with a primary provider or asthma specialist is recommended and facilitated whenever possible (Fanta, 2021b).

CASE

Emergency Department Response

Manuel, a 20-year-old college student, arrives with his girlfriend, Jimena, to the emergency department complaining that he cannot breathe. Jimena tells the triage nurse that Manuel has a history of asthma and that he has been using his controller medication only sporadically because he has no health insurance and cannot afford to refill his medication. This week she says he has been using his quick-relief inhaler every day and that today he did not have a response. She says she believes the canister is empty.

The triage nurse, Jake, immediately places Manuel in a room and positions him in high Fowler’s. He begins his assessment of Manuel and notes that the patient’s breathing is labored, he has audible wheezing, and he can speak only in two- or three-word sentences.

A focused examination shows a pulse of 122 bpm and respiratory rate of 34. Continuous pulse oximetry is begun, with initial O2 saturation of 89%. Jake applies supplemental oxygen per nasal cannula at 2 L/min and places Manuel on a cardiac monitor, which indicates sinus tachycardia.

The ED physician examines Manuel and finds he has diminished breath sounds and expiratory wheezing in all lung fields. Oxygen is increased to 3 L/min to reach an O2 saturation of 92%.

A nebulized SABA bronchodilator is begun. An IV is started, and Jake administers IV glucocorticoid. He obtains an arterial blood gas sample, which indicates hypoxia and hypercapnia.

The albuterol nebulizer treatment is repeated for a total of three treatments over the next hour. Monitoring of response to the nebulized treatment after the second treatment shows an increase in wheezing, a sign of improvement, as the bronchodilator has begun to open the airways.

After Manuel’s third treatment, his pulse is 100, respiratory rate 22, and O2 saturation 97%. Auscultation reveals improved air flow through all lung fields and only a few expiratory wheezes.

Manuel is now able to answer questions without difficulty and remains under observation in the emergency department for an hour to ensure resolution.

Prior to discharge, Manuel is given an intramuscular injection of a long-acting glucocorticoid in lieu of the fact he has not been medication adherent in the past. He is supplied with a combination controller inhaler as well as a quick-relief inhaler with instructions in their use.

An individualized asthma action plan is prepared for Manuel in collaboration with Jake, the respiratory therapist, and the physician. He is given a list of available pharmaceutical assistance programs for free or low-cost asthma medications and instructed to have a follow-up with a primary care provider within 12–24 hours. Manual is also given a list of clinicians and clinics in his area.

ASTHMA EXACERBATION MANAGEMENT IN CHILDREN

Most children with moderate or severe asthma exacerbations should be managed in an emergency department setting. Several clinical asthma severity scores for pediatric patients have been developed for use in evaluation of initial exacerbation severity, response to treatment, and determination of the need for hospitalization. These include:

- PRAM (Pediatric Respiratory Assessment Measure) uses five variables: wheezing, air entry, contraction of scalene muscles, suprasternal retraction, and oxygen saturation.

- PIS (Pulmonary Index Score) is based on five clinical variables: respiratory rate, degree of wheezing, inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio, accessory muscle use, and oxygen saturation.

- PASS (Pediatric Asthma Severity Score) is for patients ages 1–18 and includes three clinical findings: wheezing, prolonged expiration, and work of breathing.

- RAD (Respiratory rate, Accessory muscle use, and Decreased breath sounds) is used for children aged 5–17 years.

Oral systemic glucocorticoids should be started as soon as possible after arrival in the ED, followed by administration of SABA via small-volume nebulizer or metered-dose inhaler with spacer. If repeated doses are needed, they should be given every 20 to 30 minutes for three doses.

For moderate exacerbation, nebulized SABA combined with ipratropium bromide should be administered every 20 to 30 minutes for three doses or continuously for one hour.

For severe exacerbations, most children will need ongoing administration of continuous rather than intermittent nebulized SABA, unless they have a dramatic improvement after the first hour.

Children with very poor inspiratory flow or severely ill children who cannot cooperate with nebulizer therapy should be treated with epinephrine or terbutaline IM or SC. Intravenous methylprednisolone can be started as soon as intravenous access is obtained. Intravenous magnesium may also be administered if needed.

Consultation with a pediatric intensive care unit and/or anesthesia is indicated when a child has signs of impending respiratory failure, including:

- Cyanosis

- Inability to maintain respiratory effort

- Depressed mental status

- Pulse oxygen saturation <90% and/or respiratory acidosis noted on venous, arterial, or capillary blood gas sample

IV terbutaline in addition to inhaled SABAs and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation or endotracheal intubation may be indicated. Clinicians must be prepared to manage acute deterioration after intubation. The clinician most experienced in airway management should perform the procedure.

Children who have marked improvement in clinical parameters within the first one to two hours of therapy may be discharged home. Marked improvement is manifested by diminished or absent wheezing and retracting and increased aeration that is sustained at least 60 minutes after the most recent SABA dose.

Children who were moderately to severely ill on arrival and who have little improvement or worsen after initial therapy with SABAs and systemic glucocorticoids require hospitalization, including those who continue to have significant wheezing, retractions, and poor aeration. Additional factors include:

- Beta-2 agonist therapy more often than four hours

- Requirement for supplemental oxygen/low oxygen saturation on pulse oximetry an hour or more after starting therapy

- Inability to self-hydrate

- History of rapid progression of severity

- Poor adherence with outpatient medication regimen

- Recent treatment with systemic glucocorticoids or beta agonist overuse

- Inadequate access to medical care, including lack of transportation back to hospital if deterioration occurs

- Poor social support system at home, with inability of caregivers to provide medical care and supervision

(Scarfone, 2020; Sawicki & Haver, 2020)

ASTHMA EXACERBATION MANAGEMENT IN PREGNANT WOMEN

Mild and well-controlled moderate asthma can be associated with excellent maternal and perinatal pregnancy outcomes. Severe and/or poorly controlled asthma has been associated with numerous adverse perinatal outcomes as well as maternal morbidity and mortality.

Pregnant patients who present with typical mild exacerbation are placed on a cardiac monitor and pulse oximetry. Fetal heart rate monitoring is the best available method for determining whether the fetus is adequately oxygenated.

The recommended pharmacotherapy of acute asthma during pregnancy is substantially identical to the management in nonpregnant patients. When considering asthma medication use in a pregnant woman or a woman anticipating pregnancy, concerns about potential risks of asthma medication are generally outweighed by the potential adverse effects of untreated asthma. Careful follow-up by clinicians experienced in managing asthma is essential.

Inhaled corticosteroids are the preferred medication for all levels of persistent asthma during pregnancy, with the goal of maintaining adequate oxygenation of the fetus by prevention of hypoxic episodes in the mother (Morris, 2020; Schatz & Weinberger, 2020).