PATIENT SAFETY INITIATIVES

When the book To Err Is Human made headlines across the country in 1999, it captured the attention of the public and launched the modern patient safety movement. Federal funding for patient safety initiatives increased, accreditation and reporting standards tightened, and research on effectiveness of patient safety measures expanded. Over the ensuing years, the patient safety movement has grown to involve many agencies and organizations in both the public and private sectors, and many important milestones have been achieved along the way.

Annually, the Patient Safety Movement Foundation meets to nominate and elect new patient safety challenges to be addressed for the following year in attempt to reach their primary goal of zero preventable deaths by 2030. In 2020, organizations were asked to commit to implementing and sustaining a foundation for safety and reliability that includes three critical components:

- A person-centered culture of safety

- A holistic, continuous improvement framework

- An effective model for sustainment

(PSMF, 2021)

AGENCIES AND ORGANIZATIONS IN THE PATIENT SAFETY MOVEMENT

AAAHC - Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care. Develops standards to advance and promote patient safety, quality care, and value for ambulatory healthcare settings, including ambulatory surgery centers, community health centers, medical and dental group practices, medical home practices, and managed care organizations, as well as Indian Health Service and student health centers.

ABMS - American Board of Medical Specialties. Recognizes medical specialists and establishes standards for physician certification.

ACGME - Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Responsible for accrediting the majority of medical residency and internship programs.

AHRQ - Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Produces evidence to make healthcare safer, of higher quality, more accessible, more equitable, and more affordable, working with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

ANA - American Nurses Association. Represents the interests of registered nurses to advance the profession to improve healthcare.

CDC - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Promotes health and disease prevention and preparedness.

ECRI - Economic Cycle Research Institute. A federally designated Evidence-based Practice Center, recognized as a trusted source of guidance and consulting on and monitoring of new and emerging medical technologies, procedures, genetic tests, and clinical guidelines.

HCUP - Health Care Utilization Project. Maintains hospital care data enabling research on a range of health policy issues.

HRET - Health Research and Education Trust. A research and education affiliate of the American Hospital Association that promotes research and education efforts.

IHI - Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Redesigns healthcare into a system without errors, waste, delay, or unsustainable costs. In 2017, joined together with National Patient Safety Foundation.

IOM - Institute of Medicine. Asks and answers the nation’s most pressing questions about health and healthcare.

ISMP - Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Watchdog organization devoted to medication error prevention and safe medication use.

NGC - National Guideline Clearinghouse. A public resource for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.

NIH - National Institutes of Health. Conducts medical research.

NQF - National Quality Forum. Leads national collaboration to improve health and healthcare quality through measurement.

TJC - The Joint Commission. Accredits and certifies healthcare organizations and programs in the United States.

WHO - World Health Organization. WHO World Alliance for Patient Safety serves as the directing and coordinating authority for health within the United Nations system.

Federal and State Efforts

The National Action Plan centers on four foundational and interdependent areas, prioritized as essential to create total system safety:

- Culture, Leadership, and Governance

- Ensure safety is a demonstrated core value

- Assess capabilities and commit resources to advance safety

- Widely share information about safety to promote transparency

- Implement competency-based governance and leadership

- Patient and Family Engagement

- Establish competencies for all healthcare professionals for the engagement of patients, families, and care partners

- Engage patients, families, and care partners in the coproduction of care

- Ensure equitable engagement for all patients, families, and care partners

- Promote a culture of trust and respect for patients, families, and care partners

- Workplace Safety

- Implement a systems approach to workforce safety

- Assume accountabilities for physical and psychological safety and a healthy work environment

- Develop and execute priority programs that equitably foster workforce safety

- Learning System

- Facilitate both intra- and interorganizational learning

- Accelerate the development of the best possible safety learning networks

- Initiate and develop systems to facilitate interprofessional education and training on safety

- Develop shared goals for safety across the continuum of care

- Expedite industry-wide coordination, collaboration, and cooperation on safety

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced in 2007 that Medicare would no longer pay for additional costs associated with many preventable errors, including those considered “never events.” Since then, many states and private insurers have adopted similar policies. Since February 2009, CMS has not paid for any costs associated with wrong-site surgeries. Never events are also being publicly reported, with the goal of increasing accountability and improving the quality of care.

Since the National Quality Forum disseminated its original never events list in 2002, 11 states have mandated reporting of these incidents whenever they occur, and an additional 16 states mandate reporting of serious adverse events. Healthcare facilities are accountable for correcting systematic problems that contribute to the events, with some states mandating performance of a root cause analysis and reporting its results (AHRQ, 2019h).

PREVENTABLE COMPLICATIONS (NEVER EVENTS) NOT COVERED BY MEDICARE AND MEDICAID

The following preventable complications are not reimbursed by Medicare and Medicaid if acquired during an inpatient stay:

- Foreign object retained after surgery

- Air embolism

- Blood incompatibility reaction

- Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries/ulcers

- Falls and trauma:

- Fractures and dislocation

- Intracranial injuries

- Burns

- Crushing injuries

- Other injuries

- Manifestations of poor glycemic control:

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Nonketotic hyperosmolar coma

- Secondary diabetes with ketoacidosis

- Secondary diabetes with hyperosmolarity

- Catheter-associated urinary tract infection

- Vascular catheter-associated infection

- Surgical site infection following:

- Mediastinitis following coronary artery bypass graft

- Bariatric surgery for obesity

- Laparoscopic gastric bypass

- Gastroenterostomy

- Laparoscopic gastric restrictive surgery

- Surgical site infection following certain orthopedic procedures:

- Spine

- Neck

- Shoulder

- Elbow

- Surgical site infection following cardiac implantable electronic device

- Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism following total knee or hip replacement

- Iatrogenic pneumothorax with venous catheterization

Medicare and Medicaid also will not reimburse for wrong-site, wrong-procedure, and wrong-patient surgery (CMS, 2020).

Since Medicare initiated its nonpayment policy for preventable errors, many private insurers have followed suit, further benefiting patient safety. In addition, some have implemented incentives for hospitals that adhere to standards designed to improve patient safety.

Evidence-Based Practice

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.

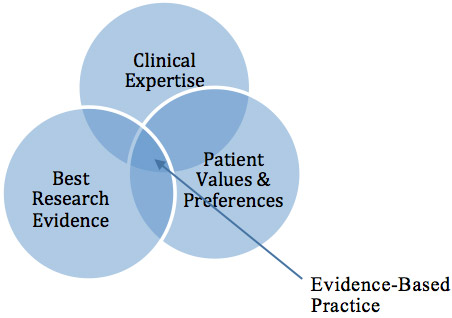

Evidence-based practice is vital for improvement in the quality of treatment and for assuring patient safety. EBP attempts to standardize practices in order to make outcomes more predictable. EBP involves collecting, evaluating, and implementing practices that can improve patient care safety and outcomes. EBP is beneficial in decreasing healthcare costs and reducing medical complications. It is the integration of clinical expertise, patients’ values and preferences, and best research evidence into the decision-making process for providing patient care (Duke University Medical Center, 2020).

Components of evidence-based practice. (Source: J. Swan.)

FIVE STEPS TO IMPLEMENT EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Evidence based practice begins and ends with the patient.

- Assess the patient and your own knowledge gaps.

- Ask a well-built clinical question derived from the patient’s case.

- Acquire evidence by selecting an appropriate resource and by conducting a search.

- Appraise evidence for validity and applicability.

- Apply what has been learned, talk with the patient, and integrate the evidence with your clinical expertise and patient preferences.

Following this process, it is important to evaluate performance with the patient (Duke University Medical Center, 2020).

CASE

Jai, a pharmacist working in skilled nursing facilities, was involved in assessing and updating a facility’s manual of medication policies and procedures. While reviewing the section on digoxin monitoring, he found that an apical pulse should be taken daily before administering digoxin and that the drug should not be given if the pulse is below 60 beats per minute.

While looking over medication administration records, he found that residents with hypertension receiving antihypertensives had their blood pressure taken once a week and other residents had vital signs done once a month. Apical pulses for residents receiving digoxin were obtained daily.

As he thought about this, he realized that in all the time he has been working as a pharmacist in healthcare facilities, he could only recall digoxin being withheld once or twice because of a pulse below 60. He began to question the necessity for performing apical pulses and asked, “Why are medication nurses in skilled nursing facilities checking apical pulses daily?”

With that question in mind, Jai began to acquire relevant resources by talking with medication nurses, directors of nursing, and other pharmacists about their experiences with digoxin monitoring. All of the nurses he questioned had been in nursing for 10 or more years in skilled nursing facilities, and none could remember holding digoxin more than once or twice for a pulse below 60 on a single day and that returned to normal on the next day. This number was compared to the hundreds of doses they had administered over their careers.

Jai then began to search databases for the best evidence for digoxin monitoring. He found that the initiation of digoxin occurred in hospital settings, and that it was critical to take apical pulses to determine the correct dosage. Once the patient was properly dosed and discharged, this monitoring was no longer required. Indeed, the research showed that patients discharged to “home” are not instructed to monitor their apical pulse every day, and there were no negative outcomes reported.

Following his critical appraisal of the resources, Jai determined that persons who reside in nursing homes have been discharged to their “home” and that medication nurses were performing a time-consuming, unnecessary procedure.

Jai brought his findings to the director of nursing and the medical director, and together they enacted (applied) a new policy that stated the apical pulse rate of residents receiving digoxin is to be obtained once a week. If the apical pulse is less than 60, digoxin should be given as ordered, and the apical pulse is to be monitored daily for three days while continuing to give the medication. If it continues to be below 60 after three days, the medication should be withheld and the attending physician notified.

The change in policy was explained to patients and their families so there would be no perception of the staff “cutting corners” once the new practice started. Aside from a few joking comments by patients about missing the “hand holding,” there was no push back.

The policy was assessed after it was in place for nine months. During that time there was not a single dose of digoxin held. It was determined that this change resulted in one less procedure to be performed by the medication nurse, leaving more time to provide other care for the patients (Vogenberg, 2004).

Attitudes towards EBP are mostly positive within the nursing, occupational therapy, and physical therapy fields. There does remain, however, resistance to acceptance of EBP despite scientifically supported knowledge. Many practices that are not evidence-based continue, including:

- Taking vital signs every 4 hours during the night on stable patients, disrupting sleep needed for recovery

- Treating children with asthma in the emergency department using nebulizers instead of a bronchodilator with a metered-dose inhaler and spacer, which has been shown to be more effective

- Removing urinary catheters only upon a physician’s order, even though a nurse-driven protocol is more efficient and may prevent urinary tract infections

- Continuing the practice of 12-hour nursing shifts when research evidence demonstrates adverse outcomes for both nurses and patients

(Meinyk, 2016)

Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement (QAPI)

Quality Assurance (QA) is the process of meeting quality standards and assuring that care reaches an acceptable level, and Performance Improvement (PI) is the continuous analysis of performance and the development of systematic efforts to improve it. Beginning in 2011, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services began mobilizing some of the best practices in nursing homes. QA and PI were combined, and a prototype QAPI program was begun in a small number of facilities, which provided the agency with best practices for helping nursing homes upgrade their current quality programs.

QAPI is made up of five elements:

- Design and Scope

- Must be comprehensive and ongoing

- Should address all systems of care and management practices

- Aims for safety and high quality with all clinical interventions

- Emphasizes autonomy and choice in daily life for residents

- Utilizes the best available evidence to define and measure goals

- Governance and Leadership

- Develops a culture that seeks input from facility staff, residents, and families

- Assures adequate resources exist

- Designates person(s) to be accountable

- Ensures staff time, equipment, and technical training as needed

- Ensures that policies are developed to sustain QAPI

- Ensures a culture of safety

- Feedback, Data Systems, and Monitoring

- Uses performance indicators to monitor a wide range of care processes and outcomes

- Reviews findings against established benchmarks or targets

- Includes tracking, investigating, and monitoring of adverse events

- Develops action plan to prevent adverse event recurrences

- Performance Improvement Projects

- Gathers information systematically to clarify issues or problems

- Intervenes to make improvements

- Systematic Analysis and Systemic Action

- Uses a systematic approach to determine when in-depth analysis is needed

- Uses a thorough and highly organized structured approach to examine the way care and services are organized or delivered

- Develops policies and procedures and demonstrates proficiency in the use of root cause analysis

- Takes systemwide actions to prevent future events

- Focuses on continual learning and continuous improvement

(CMS, 2016)