PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY

As first described above, there are several classifications of heart failure depending on the causes and duration of the illness, and HF can be any combination of these three classifications:

- Systolic vs. diastolic

- Left-sided vs. right-sided

- Acute vs. chronic

Systolic vs. diastolic heart failure refers to whether the cause of heart failure is impaired pumping of the ventricles (systolic) or impaired filling of the ventricles (diastolic). Whether the underlying problem is one of force of the contractions or altered relaxation determines whether the heart failure is considered systolic or diastolic. This is significant in that treatments vary depending upon the cause.

Left-sided HF refers to inefficient pumping of the left ventricle, leading to decreased cardiac output and therefore compromised perfusion. The volume of blood remaining in the left ventricle increases with each heartbeat, causing the blood to back up into the left atrium and eventually into the lungs. In right-sided HF the blood backs up to the right atrium and eventually to the periphery.

Acute heart failure refers to an episode of the illness that occurs suddenly or appears as an acute exacerbation of chronic HF (may be referred to as acute-on-chronic HF). Chronic heart failure occurs slowly over time, with the gradual deterioration of cardiac function resulting in worsening symptoms.

Some causes and signs/symptoms of heart failure are shown in the table below according to the chambers involved.

| Classifications | Left-sided | Right-sided |

|---|---|---|

| (Sole et al., 2020) | ||

| Systolic HF Causes |

|

|

| Diastolic HF Causes |

|

|

| Signs/Symptoms |

|

|

Neurohormonal Mediated Effects

HF with a reduced ventricular function results in a reduced cardiac output. Reduction of cardiac output can result in activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) as a compensatory mechanism. These neurohormonal responses cause physical changes in the body, particularly in the heart, kidneys, and blood vessels, as the body attempts to return to a state of homeostasis. Neurohormonal activation is one of the most common causes of the progression of heart failure.

These compensatory systems attempt to maintain a normal cardiac output by promoting retention of sodium and water, causing peripheral arterial vasoconstriction and inflammatory moderators that promote cardiac repair and remodeling. Neurohormonal activation will cause increases in cardiac preload, afterload, and left ventricular (LV) overfilling. These can lead to LV remodeling (changes in the LV shape, mass, and volume) and decreased LV pump function.

Beta-adrenergic blocking agents (beta blockers), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, aldosterone agonists, and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are prescribed for patients with HF to improve cardiac cell contractility in the failing heart caused by the activation of the neurohormonal systems in HF. The progression of HF may be reduced by beta blockers. ACE inhibitors and aldosterone agonists help prevent cardiac fibrosis in heart failure. ARBs reduce vasoconstriction, reducing the resistance against which a failing heart must pump (Hartupee & Mann, 2017).

Natriuretic peptides are hormones synthesized by the heart, brain, and other organs. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) is released by the atria in response to atrial distension and so becomes elevated in a hypervolemic state such as in HF. B-type (also call brain type) natriuretic peptide (BNP) is synthesized by the ventricles and the brain. Serum BNP levels are used to diagnose the presence and severity of HF. They work in response to the SNS and RAAS compensatory mechanism in HF; the levels indicate necessary treatment to promote the excretion of sodium and water (Klabunde, 2019).

Systolic Heart Failure

Systolic heart failure is a defect in ventricular pumping resulting in a reduced ejection fraction (EF) and referred to as heart failure with reduced EF (HFrEF). Normal EF is 55% to 60%, but with systolic heart failure, the EF is abnormally low at <40% and in severe cases as low as 5% to 10%. A new classification of midrange EF (HFmEF) has an EF of 41%–49%.

With systolic HF, the left ventricle is unable to exert enough pressure to pump sufficient blood through the aorta and out to the rest of the body. Eventually, the left ventricle becomes dilated and hypertrophied from overwork, weakening the cardiac muscle. This results in the blood backing up into the left atrium and then into the lungs, causing pulmonary congestion and edema.

Systolic HF may be caused by increased afterload (as in hypertension), impaired contractile function (as in myocardial infarction), or mechanical abnormalities such as valvular disease. Preload represents the volume of blood in the ventricles. Afterload represents the arterial resistance against which the ventricles pump blood. Abnormalities in the preload and afterload may also affect the cardiac output (Harding et al., 2020).

Systolic heart failure is also caused by various effects of aging. Aging causes a loss of elastin in the blood vessels, producing stiffness in the blood vessels. The myocardium also becomes stiffer due to a change in the effect of calcium in the cells and an abnormal growth in connective tissue. This causes ventricular hypertrophy contributing to cardiomegaly, an increase in the size or silhouette of the heart. A hypertrophied ventricle pumps less efficiently, resulting in heart failure.

Stiffness is further aggravated by interstitial collagen deposits in the cardiac tissue. The smooth muscle layers in the arteries become thicker, making them less elastic (Merck & Co, 2020).

Diastolic Heart Failure

Diastolic heart failure occurs in the presence of normal EF and is referred to as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). In diastolic heart failure, the left ventricle is stiff or noncompliant, possibly due to hypertension or aging, causing decreased filling and high filling pressures and resulting in a reduction in cardiac output. Approximately 50% of patients with HF have HFpEF.

The reduced preload (ventricular volume) results in a diminished stroke volume (SV). As stroke volume is part of the cardiac output (CO) equation (SV x HR = CO), there is a diminished amount of blood pumped by the left ventricle into the systemic circulation.

The noncompliance of the ventricle is usually caused by hypertension. An imbalance in normal cardiac contraction and relaxation can also be due to the change in calcium function that occurs when there is an insufficient reuptake of calcium ions into the cardiac cells. Heart failure interferes with the normal reabsorption of calcium into the heart muscle. This causes the tissue to become weaker, creating a vicious cycle as the weak tissue is less able to reabsorb calcium (Merck & Co, 2020).

The characteristics of the patients with HFpEF are older age, more likely to be female, and greater prevalence of hypertension, obesity, and anemia than those with HFrEF (Benjamin et al., 2020).

HEART FAILURE AND DECREASED CIRCULATION

Any form of heart failure may result in decreased blood flow. Whether the HF is secondary to poor ventricular filling (diastolic) or a weak pump (systolic), the end result is less systemic perfusion and increased congestion at the cellular level. Poor perfusion to major organs may result in progressive organ failure. Poor renal perfusion may result in decreasing kidney function as evidenced by a decreasing glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Decreased cerebrovascular circulation in the form of reduced basilar artery inflow may lead to irreversible cognitive or motor impairment, as in the case of a stroke (Harding et al., 2020).

Left-Sided Heart Failure

The most common type of heart failure is left-sided HF. It results in decreased cardiac output and increased pulmonary venous pressure as the incompletely emptied left cardiac chambers cause compromised blood flow. The left ventricle is unable to receive the blood from the left atrium, since it remains partially filled, which then makes the left atrium unable to receive the normal amount of blood from the lungs, thereby causing the lungs to become congested.

When the pulmonary artery capillary wedge pressure (PACWP) is greater than 24 mmHg, the capillaries begin to leak into the alveoli and interstitial space, escalating the work of breathing. The resultant pulmonary edema forces deoxygenated blood through the congested alveoli, diminishing the arterial oxygen content. The ability of the lungs to process deoxygenated blood and oxygenate it is significantly compromised, resulting in excessive fluid accumulation in the lungs and dyspnea.

The following are common symptoms of left-sided heart failure:

- Dyspnea

- Orthopnea

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND)

- Cyanosis

- Pulmonary edema

- Pink, frothy sputum

- Activity intolerance

- Congestion of liver (higher pressures in the hepatic veins/inferior vena cava) and gastrointestinal tract (edema caused by increased intestinal permeability)

Some possible causes of left-sided HF include:

- Chronic coronary artery blockage

- Hypertension

- Excessive alcohol intake

- Myocardial infarction

- Valvular defects

- Thyroid disorders

- Heart muscle infection

- Abnormal vasculature

(Harding et al., 2020; Merck & Co, 2020)

Right-Sided Heart Failure

Right-sided heart failure may be systolic or diastolic depending on whether the cause of failure relates to insufficiency of blood pumped out by the heart due to a weak pump or low volume. In right-sided HF, the right ventricle does not empty completely, causing the blood left in the chamber to back up into the right atrium. The elevated systemic venous pressure causes edema in dependent tissue and the abdominal viscera (ascites). This primarily affects the liver, but the stomach and intestines can also become congested. Dependent tissue edema will cause a delayed venous return of fluid and hypertension (Merck & Co, 2020).

Some common right-sided heart failure symptoms are:

- Swelling of the feet and ankles

- Accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity (ascites)

- Hepatomegaly

- Jugular vein distension

- Anorexia, GI distress, weight loss

The most common causes of right-sided HF are:

- Chronic pulmonary diseases

- Pulmonary embolism

- Cor pulmonale (right ventricle dilation and hypertrophy)

- Congenital heart disease

- Primary pulmonary hypertension

- Heart valve disease

- Left-sided HF

- Right ventricular infarction

(Harding et al., 2020; Merck & Co, 2020)

CASE

Mi-Young, an 84-year-old woman, is brought by her granddaughter to the urgent care clinic complaining of swelling in her feet and ankles, infrequent urination, and difficulty walking. Angela, the family nurse practitioner, gets the patient settled in an exam room and performs a head-to-toe examination.

Angela notices that Mi-Young is walking slowly and with great difficulty and must lean heavily on her granddaughter’s arm for support. She observes 3+ pitting edema of the feet and ankles, abdominal distention with ascites, a palpable liver, and 3+ jugular vein distention when sitting upright on the exam table. Mi-Young’s vital signs are BP 168/94 mmHg, pulse 122, respirations 18, deep and unlabored, temperature normal, and an O2 saturation of 89% on room air. An EKG shows a sinus tachycardia with occasional unifocal PVCs.

Angela suspects right-sided HF, explains her findings to Mi-Young, and arranges for EMT transport to the nearest hospital. She notifies the patient’s primary care provider. She explains to the patient and her daughter that they will be given information to help them better understand how to take care of Mi-Young to address what is causing her symptoms and to prevent the same thing from happening again, thereby preventing a hospital stay. Angela clarifies that a plan of cardiac rehabilitation may be put into place to help her cope with her symptoms.

Acute Heart Failure

Acute heart failure is the sudden onset of the signs and symptoms of HF, resulting in an urgent medical condition requiring immediate intervention. It may also manifest as the pulmonary edema that results after an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the lungs. This fluid compromises oxygenation, making it difficult for the patient to breathe. The heart starts to beat faster as a compensatory mechanism to improve oxygenation. The rapid heart rate causes the heart muscle to become exhausted, forming the foundation for the blood to become backed up or congested.

Acute HF typically occurs after a sudden insult to the myocardium, such as a myocardial infarction (MI). It may result in pulmonary edema if there is insult to the left ventricle. The following are common causes of acute heart failure:

- MI

- Liver failure

- Kidney failure

- Hematological conditions (such as anemias and coagulopathies that cause hemodynamic imbalance and edema)

- A sudden exacerbation of a chronic disease (acute-on-chronic HF)

The symptoms of acute HF are:

- Production of frothy, pink sputum with coughing

- Auscultation of adventitious breath sounds such as crackles

- Hypoxia that may result in panic/anxiety, tachycardia, shortness of breath, restlessness, orthopnea, or confusion

- Jugular vein distention

- Cyanosis

(Harding et al., 2020)

Chronic Heart Failure

Chronic heart failure is a syndrome of ongoing ventricular dysfunction characterized by a progressive worsening of symptoms in which the heart no longer supplies adequate blood volume to satisfy the body’s circulatory needs. Once there is a reason for the heart to begin failing—for instance, as chronic hypertension or an acute injury such as a myocardial infarction—the heart works harder to compensate for decreased output, and the increased cardiac workload causes the heart to fail even more.

The following are general clinical manifestations of chronic heart failure:

- Fatigue

- Dyspnea

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND)

- Tachycardia

- Edema

- Nocturia

- Skin changes

- Behavioral changes

- Chest pain

- Weight changes

(CDC, 2020a; Harding et al., 2020)

When a patient with chronic HF has an acute exacerbation with increased symptoms, it may be referred to as acute-on-chronic HF.

CASE

Antoinette is a 75-year-old, morbidly obese African American woman who is admitted to Sunshine Coast Hospital for the fifth time for recurring symptoms of heart failure. It has been 18 days since her last admission for these same symptoms. She has a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, and hypothyroidism. Her physician has ordered dietary and physical therapy consultations to support her in her efforts to lose weight and control her blood sugar.

At her initial physical therapy consultation, she seems downcast and dejectedly tells the evaluating therapist, Warren, that everyone in her family has some form of heart disease and “there’s just nothing I can do about it.” Warren validates Antoinette’s feelings by agreeing that genetic risk factors for heart disease cannot be helped and are a valid concern. He then goes on to discuss the fact that other modifiable risk factors, such as weight, blood pressure, and blood sugar, are more within Antoinette’s control and that her multidisciplinary healthcare team will help her to gain more control over these factors.

Antoinette brightens a bit at this and tells Warren about her recent dietary consult, where the dietitian recommended a diabetes diet in order to help get her weight and blood pressure under better control. Warren tells Antoinette that physical therapy can also help with these factors and that the two of them will work together to craft a realistic and progressive cardiopulmonary conditioning program of therapeutic exercises.

Antoinette diligently follows the recommendations of her dietitian and goes to PT twice weekly for a period of eight weeks. On her last day of PT, she proudly tells Warren that she has been experimenting with a heart-healthy cookbook and now uses olive oil in place of canola oil and wheat bread instead of white. She is happy to report that her blood sugar has lowered by several points, she has lost 7 pounds, and she feels more in control of her food choices. When Antoinette finishes her last PT session, she is noticeably less fatigued and less short of breath than she was at her first session. Warren takes her blood pressure and announces that it, too, has lowered significantly over the past two months.

Antoinette and Warren review a long-term exercise program for Antoinette to continue independently at home, including an after-dinner walk, working in her newly planted vegetable garden, and joining a weekly aquatic exercise class at the local senior center. As she leaves the clinic, Antoinette gives Warren a hug, thanks him for helping her to feel more in control of her health and promises to bring him some tomatoes from her garden.

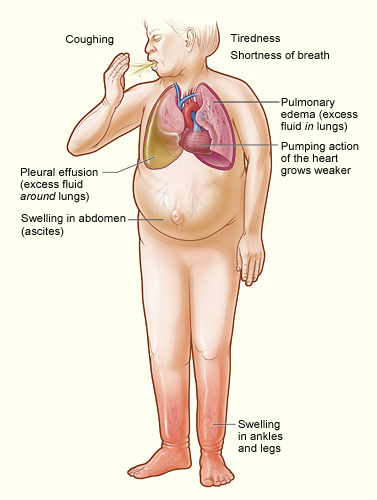

Major signs and symptoms of heart failure. (Source: NHLBI, 2020d.)

Risk Factors

Risk factors for heart failure include:

- Advanced age

- Dietary and lifestyle factors

- Obesity

- Genetic disposition

Comorbidities may also put someone at greater risk for HF and include:

- Myocardial infarction

- Hypertension

- Diabetes

- Renal failure

- Metabolic syndrome

- Untreated sleep apnea

(Benjamin et al., 2020; CDC, 2020a)

Advanced age (>70 years) usually results in increased afterload due to increased arterial resistance. This is caused by thickening of the smooth muscle and a loss of elastin in the blood vessels. Calcium changes and interstitial collagen deposits in the myocardium cause a loss of elasticity, affecting the ability to pump blood out of the ventricles.

Women experience a higher occurrence of diastolic failure than men. Women with diabetes are more predisposed to HF. Women have a higher incidence of obesity, which is another risk factor for HF. Women also have a higher incidence of increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, or preload.

Dietary and lifestyle factors also impact HF risk. HF is higher in males with hypertension, whereas healthy lifestyle factors (normal weight, not smoking, regular physical activity, moderate alcohol intake, and consumption of fruits and vegetables) are related to lower risk of HF. The use of tobacco products containing nicotine causes the release of catecholamines, resulting in the vasoconstriction that causes hypertension, and hypertension causes increased vascular resistance that may cause HF over time.

Obesity may be a precipitating factor for HF. It can be associated with diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension, all common comorbidities with HF.

Individuals may be predisposed to acquiring HF because of specific genes or gene mutations they have inherited. Cardiovascular disorders such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, and cardiomyopathy (a weakening of the heart muscle) all have a genetic link and may predispose a patient to HF. Cardiomyopathy alone may be connected to as many as 40 defective genes (Harding et al., 2020).

Cocaine causes cardiac injury through both ischemic and toxic pathways. Cocaine increases the synaptic catecholamine concentration, producing coronary vasoconstriction. Prolonged cocaine use results in ischemia producing cell death and myocardial fibrosis. Myocardial toxicity plays a major role in cocaine-induced cardiac injury. Chronic alcohol consumption can cause extensive oxidative injury to the mitochondria. Marijuana-induced coronary vasospasm and tachycardia, in conjunction with excessive cocaine use, may contribute to a risk of sustaining a myocardial infarction (Chapel & Husain, 2018).

African Americans have a greater proportion of HF risk (68%) than Whites (49%), which is largely attributable to modifiable risk factors such as elevated systolic blood pressure, hyperglycemia, coronary heart disease, left ventricular hypertrophy, and smoking (Benjamin et al., 2020).

The American Heart Association’s “Life’s Simple 7” guidelines are associated with a lower lifetime risk of HF. They include stopping smoking, lower BMI, physical activity for at least 30 minutes at least five times per week, healthy diet, lower-range cholesterol, BP <140/90 mmHg, and glucose within advised parameters (Benjamin et al., 2020).