DIAGNOSING METABOLIC SYNDROME

Diagnosing metabolic syndrome requires a physical examination and blood tests.

Medical History

The medical history offers important information that can help to confirm the diagnosis and determine the extent of the problem. A person who has metabolic syndrome may already have been diagnosed with some components of the syndrome, such as obesity, hypertension, or dyslipidemia. A major complication of the syndrome (atherosclerotic artery disease, ischemic heart disease, diabetes) may also be present.

In addition, the person may come with a diagnosis (or the signs and symptoms) of one of a number of other medical problems that occur especially frequently with metabolic syndrome. Diseases that often present with metabolic syndrome include:

- Obesity

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- Cardiovascular disease

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Chronic kidney disease

(NHLBI, 2019; Durkin, 2019)

Any of these problems should alert clinicians to the possibility of metabolic syndrome.

Diagnostic Criteria

As stated earlier, metabolic syndrome is diagnosed if three or more of the following traits are present:

- Large waist circumference: Waist circumference >102 cm (>40 inches) in men, >89 cm (>35 inches) in women

- High blood triglyceride level: 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or higher (or on triglyceride-lowering medication)

- Reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol: <40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) in men, <50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) in women

- Increased blood pressure: 130/85 mmHg or higher (or already diagnosed with hypertension)

- Elevated fasting blood sugar: >100 mg/dL

(NHLBI, 2019)

INTRA-ABDOMINAL FAT

Today, the standard physical examination of a patient includes height and weight, but it does not usually include a measurement that is essential for diagnosing metabolic syndrome: the patient’s waist circumference. The specific aspect of obesity that best warns of future cardiovascular problems is the amount of fat concentrated inside the abdomen (AHA, 2016), and waist circumference is a good measure of intra-abdominal fat.

Measuring Obesity

The most commonly used measure of obesity is the body mass index (BMI). This is measured using the formula:

BMI = weight in kilograms/height in meters squared

or

BMI = weight in pounds x 703/height in inches squared

BMI has been shown to be a good indirect indication of the percentage of body fat, and it is the most commonly used measure of total body fat. The BMI obesity definitions for adults are as follows (CDC, 2020a):

| Classification | BMI (kg/m2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 18.5–24.9 | |

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 | |

| Obese | Class 1 | 30.0–34.9 |

| Class 2 | 35.0–39.9 | |

| Class 3 (extreme obesity) | >40.0 | |

Obese people are more likely than people of normal weight to suffer from certain medical problems, including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemias, polycystic ovarian syndrome, degenerative joint disease, sleep apnea, cancer (specifically, breast, colon, endometrial, prostatic), gastroesophageal reflux disease, fatty liver disease, and gallstones.

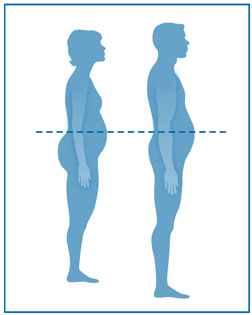

All overweight people have an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome. In overweight and class 1 obese people, the risk of having or developing metabolic syndrome is much greater if their excess fat is located inside the abdomen (i.e., visceral). When excess fat is concentrated in the abdomen, a person will have a round, apple shape. This is called android obesity, and of all shapes, it is the most strongly predictive of metabolic syndrome–related conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemias, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. (Another common shape of obesity has excess fat concentrated lower on the body, in the hips and thighs. This gives a person a pear shape and is called gynecoid obesity.)

Measuring Waist Circumference

Many large studies have shown that simply measuring a person’s waist circumference gives a good indication of the amount of excess body fat that is located inside the abdomen. A waist circumference of >94 cm (37 inches) in men and >80 cm (31.5 inches) in women is considered a warning sign, and a circumference of >102 cm (40 inches) in men and >89 cm (35 inches) in women puts the person in the high or very high risk category for developing metabolic syndrome and its serious health consequences.

The waist is the narrow band of the abdomen below the lowest margin of the ribs and above the top (iliac crest) of the hipbones. To measure the waist:

- Place the tape measure around the abdomen, just above the hip bone.

- Hold the tape measure snug to the skin and parallel to the floor.

- Measure with the patient relaxed and breathing normally.

Measuring tape position for waist circumference. (Source: Adapted from CDC.gov.)

CASE

Sharon, Age 52

Sharon is a 52-year-old female patient who has come to the physician’s office for an initial appointment to help manage her hypertension and joint pain. Sharon appears to be obese, with an android shape, prompting the nurse, Jennifer, to measure her waist circumference, which is 92 cm. After weighing Sharon and measuring her height, Jennifer calculates the patient’s BMI as 35.2 kg/m2. Sharon’s blood pressure is measured today at 187/93 mmHg after resting for 5 minutes.

Jennifer draws the patient’s blood and sends the samples to the lab for a fasting glucose level and total lipid panel. Jennifer then asks Sharon about her recent medical history. Sharon reports having pain in her joints, occasional difficulty breathing, excessive thirst, and having to get up several times during the night to urinate.

Sharon also reports that her mother has a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and her father has heart disease; additionally, both of her parents have high cholesterol and taking medication for it. She states that for the past 10 years, she has had increasing problems keeping her weight under control and even more so now that she has gone through menopause. She states that she would like to exercise more, but with the excess weight and joint pain, she has not been able to perform any regular exercise.

Jennifer suspects that Sharon may have metabolic syndrome, with possible coexisting hypertension, osteoarthritis, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and asthma, and discusses her beliefs with Sharon’s physician. They also discuss Sharon’s desire to incorporate exercise into her normal routine. Jennifer helps Sharon with scheduling an initial appointment with a physical therapist for an evaluation and exercise recommendations with a focus on weight loss.

Sharon is scheduled for a return visit to review the results of her blood tests and discuss possible therapeutic recommendations, including both lifestyle changes and medications to control her blood pressure and manage her other coexisting conditions.

(continues)

HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE

The second component of metabolic syndrome that can be picked up in a physical exam is high blood pressure. To be used as a diagnostic condition for metabolic syndrome, a person’s blood pressure must be >130/85 mmHg. (If a person is already taking antihypertensive medication, it is assumed that their blood pressure would normally be >130/85 mmHg.)

| Level | Systolic | Diastolic |

|---|---|---|

| (AHA, 2017) | ||

| Normal | <120 | <80 |

| Elevated | 120–129 | <80 |

| Hypertension, stage 1 | 130–139 | 80–89 |

| Hypertension, stage 2 | >140 | >90 |

| Hypertensive crisis | >180 | >120 |

CASE

Sharon, Age 52 (continued)

Sharon returns for a follow-up appointment with her physician. At her previous appointment, her blood pressure was 187/93 mmHg. The nurse, Jennifer, measures the patient’s blood pressure once again; this time the reading is 189/94 mmHg.

At this time, Sharon’s blood test results have come in, and they show a blood triglyceride level of 155 mg/dL and an HDL cholesterol level of 43 mg/dL. Her fasting blood glucose level is 142 mg/dL.

Based on the previous visit’s assessment of an abnormal waist measurement and hypertension, the nurse suspects that Sharon has metabolic syndrome. The physician confirms the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome and outlines a treatment plan for Sharon, including appropriate diet and exercise as well as adhering to her prescribed medication regimen to control her blood sugar, lipid, and blood pressure levels. The physician refers Sharon to a dietitian for nutrition recommendations, as well as instructs her to continue to see the physical therapist for an individualized exercise program.

At the next follow-up appointment, Jennifer reviews with Sharon her new treatment recommendations for following a Mediterranean diet from the dietitian and her current therapeutic exercise program from her physical therapist to make sure that she understands and is incorporating the recommendations from these providers. Sharon reports that she is scheduled to see the physical therapist again soon, who will continue to progress her therapeutic regimen and monitor any changes over the next four weeks. Jennifer then reminds the patient to schedule another follow-up visit in one month with the physician and herself to monitor Sharon’s symptoms and progress.

Laboratory Tests

It is important to measure two other factors that contribute to metabolic syndrome: insulin resistance and dyslipidemias. In evaluating a patient who is at risk for metabolic syndrome, laboratory testing includes both fasting glucose levels and fasting lipid profiles.

ASSESSING INSULIN RESISTANCE

Among the various measurements of the body’s ability to produce and use glucose, the blood level of glucose after an 8-hour fast is probably the simplest. Fasting glucose levels are a well-calibrated standard that is now widely used to screen for insulin resistance, a common cause of diabetes.

Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is an endocrine disease that disrupts the body’s energy metabolism. In diabetes there is an insufficient amount of insulin available to the cells, and therefore glucose is not used efficiently throughout the body. Diabetes is diagnosed when any one of the following hyperglycemic conditions is present:

- Fasting blood glucose level ≥126 mg/dL

- Hemoglobin A1C level ≥6.5% (an index measuring the amount of glucose sticking to hemoglobin inside red blood cells, and which indicates a person’s average blood glucose level over the past two to three months)

- Two-hour plasma glucose level ≥200 mg/dL in an oral glucose tolerance test

- Random plasma glucose level ≥200 mg/dL, accompanied by classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis

(Durkin, 2019; ADA, 2020a; Mayo Clinic, 2020a)

Hyperglycemia

Hyperglycemia can result from a variety of causes. A fasting blood sugar >100 mg/dL is one of the primary indicators of metabolic syndrome (Mayo Clinic, 2019a). The two most common causes are decreased secretion of insulin and insulin resistance.

ASSESSING DYSLIPIDEMIAS

Dyslipidemias are conditions in which the bloodstream contains unhealthy amounts of lipids. The dyslipidemias of metabolic syndrome are: 1) elevated blood levels of triglycerides and 2) reduced blood levels of high-density lipoproteins. Metabolic syndrome is often accompanied by additional dyslipidemias, although these abnormalities are not necessary for the diagnosis of the syndrome.

Classification of blood lipid levels are given in the table below:

| Type | Blood Concentrations (mg/dL) (Measured after an 8-hour fast) |

|---|---|

| (Labtestsonline.org, 2020; Mayo Clinic, 2016a) | |

| Triglycerides |

|

| HDL cholesterol |

|

| LDL cholesterol |

|

Metabolic syndrome is characterized by fasting blood triglycerides >150 mg/dL and fasting blood HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women (NHLBI, 2019).

CASE

George, Age 45

George is a 45-year-old male patient who comes to the clinic for his annual physical. After stepping onto a scale, he is found to have gained 10 pounds over the previous year. His blood pressure has gradually been increasing over the past two years as well, with a current measurement of 145/88 mmHg.

As his medical and family history is taken, George mentions that his mother has type 2 diabetes and that his uncle was diagnosed with heart disease after suffering a heart attack at age 55. The nurse takes a measurement of his waist circumference, which is 105 cm (41 inches).

After discussing George’s physical assessment findings with the physician, a lipid panel is ordered. Three days later, the results of George’s lipid panel show a blood triglyceride level of 156 mg/dL and a HDL cholesterol level of 38 mg/dL.

George is diagnosed with metabolic syndrome; he is started on appropriate therapy, instructed on incorporating lifestyle interventions (e.g., diet, exercise), and referred to a dietitian at his request. A follow-up appointment is scheduled for three months later to assess how he is doing with initial management of his condition.

When George returns for his follow-up visit, he reports that he has been following his diet and exercise plan and feels that this has made a difference in how he is feeling. He has lost 8 pounds, his blood pressure is now 124/68, his triglycerides have improved to 130 mg/dL, and his HDL cholesterol has increased to 52 mg/dL.

George continues to be motivated to make changes in order to improve his health and states that he feels better than ever. He adds that his wife has been very supportive. Together they joined the local Weight Watchers to support a healthy diet and weight loss program, and they are exercising on a regular basis.

Two Possible Coexistent Diagnoses

Patients with intra-abdominal obesity, high fasting glucose levels, high blood pressure, high blood levels of triglycerides, and low blood levels of HDL cholesterol have metabolic syndrome and should be treated. Yet it is important to remember that a patient may simultaneously have other diseases with similar or overlapping symptoms. Two specific disorders to keep in mind are Cushing’s syndrome and hypothyroidism.

CUSHING’S SYNDROME

Cushing’s syndrome is caused by excess glucocorticoid, either excess intrinsic cortisol (as is produced by the adrenal glands in Cushing’s disease) or excess extrinsic glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone), which might have been prescribed to treat another disorder. Typically, a person with Cushing’s syndrome has weight gain, skin striae (stretch marks), hirsutism, and proximal muscle weakness (Durkin, 2019).

As in metabolic syndrome, Cushing’s syndrome leads to central (as opposed to peripheral) obesity. Cushing’s syndrome also includes hypertension, elevated blood glucose levels, and dyslipidemias, including an elevated level of blood triglycerides. Moreover, patients with Cushing’s syndrome are more susceptible to cardiovascular disease (Durkin, 2019).

HYPOTHYROIDISM

Hypothyroidism is caused by a decreased secretion of thyroid hormone from the thyroid gland, slowing metabolic processes throughout the body. As in metabolic syndrome, people with hypothyroidism tend to be overweight and inactive. They also have dyslipidemia and, sometimes, mild hypertension. Moreover, patients with hypothyroidism are more likely than normal to have cardiovascular disease. On the other hand, unlike metabolic syndrome, low blood glucose levels are typical of hypothyroidism (Durkin, 2019).

Comorbid Diseases Associated with Metabolic Syndrome

People with metabolic syndrome are at risk for a long list of health problems. It is not always clear whether metabolic syndrome is the cause or whether the related disorders share common causes with the components of metabolic syndrome. Two serious comorbidities that may result from long-term metabolic syndrome are coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

CORONARY HEART DISEASE

The most striking risk posed by metabolic syndrome is coronary heart disease (also known as coronary artery disease or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease). By themselves, the dyslipidemias of metabolic syndrome (i.e., high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol levels) encourage plaque to form along the walls of arteries. When combined with the other components of metabolic syndrome, these atherogenic dyslipidemias (i.e., those that tend to cause atherosclerotic plaque) put a person at high risk for developing serious atherosclerotic vascular disease with coronary artery blockage.

People who have metabolic syndrome often also have low-level inflammation throughout the body and blood clotting defects that increase the risk of developing blood clots in the arteries. These conditions contribute to increased risk for cardiovascular disease (NHLBI, 2019).

TYPE 2 DIABETES

Metabolic syndrome is a precursor to type 2 diabetes. The mechanism is as follows: The insulin resistance of metabolic syndrome forces the pancreas to secrete higher than normal amounts of insulin. Meanwhile, some hyperglycemia persists even with the excess circulating insulin. The continuous hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia are toxic to the beta cells in the pancreas, and over time these cells weaken and the amount of insulin that they produce decreases. Eventually, the pancreas cannot cope with hyperglycemia, and the patient develops diabetes.