PRACTICES AND CONTROLS

In addition to the precautions described above, other practices and controls can be employed to prevent and control infection. These include:

- Engineering controls

- Work practice controls

- Environmental controls

Types of Practices and Controls

Engineering controls are measures that protect workers by removing hazardous conditions or by placing a barrier between the worker and the hazard. Examples include:

- Sharps disposal containers

- Self-sheathing needles

- Sharps with engineered sharps injury protections

- Needleless systems

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA, 2012), engineering controls shall be examined and maintained or replaced on a regular schedule to ensure their effectiveness.

ENGINEERING CONTROL DEVICE EXAMPLES

Syringe with retractable needle.

Self-resheathing needle.

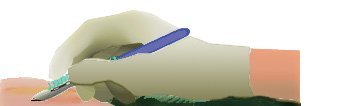

Resheathing disposable scalpel.

Phlebotomy needle with hinged shield as an add-on safety feature.

(OSHA, 2020)

Work practice controls reduce the likelihood of exposure to pathogens by changing the way a task is performed, such as:

- Practices for handling and disposing of contaminated sharps

- Handling specimens

- Handling laundry

- Cleaning contaminated surfaces and items

- Performing hand hygiene

(OSHA, 2012)

Environmental controls help prevent the transmission of infection by reducing the concentration of pathogens in the environment. Such measures include but are not limited to:

- Appropriate ventilation

- Environmental cleaning (housekeeping)

- Cleaning and disinfecting strategies (including food service areas)

- Cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization of patient care equipment

- Proper linen and laundry management

- Disposal of regulated medical waste

(CDC, 2019e)

Sharps- and Injection-Related Practices and Controls

Engineering, work practice, and environmental controls have all been developed to prevent and control the spread of infection related to the use of needles and other sharps in the healthcare setting.

SHARPS HANDLING

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), part of the U.S. Department of Labor, first published the Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens Standard in 1991. In 2001, in response to the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act, OSHA revised the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. The Bloodborne Pathogens Standard is updated regularly, with the most recent update being April 2012.

OSHA requirements for handling sharps state that contaminated sharps are needles, blades (such as scalpels), scissors, and other medical instruments and objects that can puncture the skin. Contaminated sharps must be properly disposed of immediately or as soon as possible in containers that are closable, puncture-resistant, leak-proof on the sides and bottom, and color-coded or labeled with a biohazard symbol.

- Discard needle/syringe units without attempting to recap the needle whenever possible.

- If a needle must be recapped, never use both hands. Use the single-hand “scoop” method by placing the cap on a horizontal surface, gently sliding the needle into the cap with the same hand, tipping the needle up to allow the cap to slide down over the needle, and securing the cap over the needle with the same hand.

- Never break or shear needles.

- To move or pick up needles, use a mechanical device or tool, such as forceps, pliers, or broom and dustpan.

- Use blunt-tip suture needles to decrease risk of percutaneous injury.

- Dispose of needles in labeled sharps containers only. Sharps containers must be accessible and maintained upright.

- When transporting sharps containers, close the containers immediately before removal or replacement to prevent spillage or protrusion of contents during handling or transport.

- Fill a sharps container up to the fill line or two thirds full. Do not overfill the container.

(OSHA, 2012)

CASE

Joanne is a circulating nurse assigned to the operating room (OR) procedure room. She has just finished caring for a patient who required a lumbar epidural steroid injection. The anesthesiologist performing the procedure left the lumbar puncture procedure tray for Joanne to clean up, as he was needed on another case in another room. Joanne is under pressure to turn over the procedure room quickly because there is a full patient schedule for the day.

As Joanne is cleaning up the tray, she sticks herself with the used lumbar puncture needle, not realizing that the syringe was left in the open wrapper of the disposable tray. As per well-publicized policy, the needle should have been discarded in a sharps container by the anesthesiologist after use.

Joanne promptly flushes the needlestick injury and reports the incident to her immediate supervisor. The report includes the fact that the injury occurred in the procedure room of the OR while cleaning up after a lumbar puncture. Her supervisor starts the process of investigation and exposure management.

The infection control team is also alerted and assists with formal reporting, feedback to the anesthesiologist on duty, and recommended postexposure protocols. The infection control team works with the entire OR team to review and reinforce safe handling of sharps and needlestick prevention as a result of this incident.

SAFE INJECTION PRACTICES

Unsafe injection practices put patients and healthcare providers at risk for infection. Safe injection practices are part of Standard Precautions and are aimed at maintaining a basic level of patient safety and provider protections. A good rule to remember regarding safe injections is “One Needle, One Syringe, One Time.”

Healthcare providers are required to follow CDC-recommended practices for injection and/or IV therapy:

- Draw up medications in a designated clean medication preparation area that is not adjacent to potential sources of contamination, including sinks or other water sources. Clean and disinfect the medication preparation area on a regular basis and any time there is evidence of soiling.

- Perform proper hand hygiene prior to handling medications.

- Access parenteral medications in an aseptic manner, using a new sterile syringe and sterile needle.

- Prepare an injection as close as possible to the time of administration to prevent compromised sterility.

- Disinfect the rubber septum with alcohol and allow to dry.

- Do not leave a needle inserted into a medication vial septum for multiple use.

- Always enter a medication vial with a sterile needle and sterile syringe, even when obtaining additional doses of medication for the same patient, and discard after use.

- Use a syringe and needle only once to administer a medication to a single patient. Do not use the same syringe to give an injection to more than one patient.

- Do not use a syringe for patient after using it to inject medications into an IV tubing port of another patient, even if that tubing port is several feet away from the IV catheter site.

- Vials labeled as single-dose or single-use should be used for only a single patient as part of a single case, procedure, or injection.

- If a single-dose or single-use vial appears to contain multiple doses or more medication than needed for a single patient, do not use for another patient or store for future use for the same patient.

- If a single-dose or single-use vial will be entered more than once for a single patient as part of a single procedure, use a new needle and new syringe each time. Discard the vial at the end of the procedure; do not store for future use.

- Do not combine (pool) leftover contents of single-dose or single-use vials or store single-dose or single-use vials for later use.

- Multi-dose vials should be dedicated to a single patient whenever possible. If used for more than one patient, keep and access in a dedicated clean medication preparation area.

- If a multi-dose vial enters an immediate patient treatment area (operating room, procedure room, anesthesia and procedure carts, and patient rooms or bays) it should be dedicated for single-patient use only.

- Discard medications according to the manufacturer’s expiration date (even if not opened) and whenever sterility is compromised or questionable.

- If a multi-dose vial has been opened or accessed, the vial should be dated and discarded within 28 days unless manufacturer specifies a different length of time or date.

- Single-dose vials that have been opened or accessed should be discarded according to the manufacturer’s time specifications or at the end of the case/procedure for which it is being used. Do not store for future use.

(CDC, 2019f)

Safe injection practices are also described by OSHA. They include:

- Contaminated needles and other contaminated sharps shall not be bent, recapped, or removed except as noted below. Shearing or breaking of contaminated needles is prohibited.

- If an employer can demonstrate that no alternative is feasible or that such an action is required by a specific medical or dental procedure, bending, recapping, or needle removal must be accomplished through the use of a mechanical device or one-handed “scoop” technique (see above).

- Immediately or as soon as possible after use, contaminated reusable sharps shall be placed in appropriate containers until properly reprocessed. Reusable sharps that are contaminated with blood or OPIM shall not be stored or processed in a manner that requires employees to reach by hand into the container.

(OSHA, 2012)

Cleaning, Disinfecting, and Sterilizing

The healthcare environment can easily become contaminated with pathogens. The potential for contamination exists in every area of the hospital or other healthcare facility. Contaminated patient-care equipment (e.g., wet or soiled dressings), invasive devices that were used in diagnosis and treatment (e.g., surgical instruments or endoscopes), and environmental surfaces (e.g., doorknobs, floors, toilets) can act as vehicles for the transmission of infection to healthcare workers and/or patients. In addition, contamination depends on:

- The potential for external contamination (e.g., presence of hinges, crevices)

- The potential for internal contamination (e.g., presence of lumens)

- The physical composition, design, or configuration of an instrument, medical device, equipment, or environmental surface

GENERAL ENVIRONMENTAL SURFACE CLEANING

Transmission of infections to either staff or patients is largely via hand contact with a surface. Thus, cleaning and disinfecting environmental surfaces is fundamental to reducing the incidence of HAIs.

The number and type of pathogens present on environmental surfaces are affected by:

- Number of people in the environment

- Amount of activity

- Amount of moisture

- Presence of material able to support microbial growth

- Rate at which organisms suspected in the air are removed

- Type of surface and orientation (horizontal or vertical)

Cleaning is the first step of any sterilization or disinfection process and requires the physical action of scrubbing with detergents and surfactants and rinsing with water.

Cleaning is followed by disinfection. The following are factors that influence the choice of disinfection procedure for environmental surfaces:

- The nature of the item to be disinfected

- The number of microorganisms present

- The innate resistance of those microorganisms to the inactivating effects of a germicide

- The amount of organic soil present

- The type and concentration of germicide used

- The duration and temperature of germicide contact

Environmental surfaces can be divided into medical equipment surfaces (e.g., knobs or handles on equipment) and housekeeping surfaces (e.g., floors, walls, and tabletops).

Manufacturers of medical equipment provide care and maintenance instructions specific to their equipment. These instructions include information about:

- The equipment’s compatibility with chemical germicides

- Whether the equipment is water-resistant or can be safely immersed for cleaning

- How the equipment should be decontaminated if servicing is required

Use barrier protective coverings as appropriate for equipment surfaces that are:

- Touched frequently with gloved hands during the delivery of patient care

- Likely to become contaminated with blood or body substances

- Difficult to clean (e.g., computer keyboards)

Most, if not all, housekeeping surfaces (e.g., floors, walls, tabletops) must be cleaned on a regular basis using only soap and water or a detergent/disinfectant, depending on the nature, type, and degree of contamination. Spills must be cleaned up promptly. Walls, blinds, and window curtains in patient-care areas are cleaned when visibly dusty or soiled.

High-touch housekeeping surfaces in patient-care areas (e.g., doorknobs, bedrails, light switches, wall areas around the toilet in the patient’s room, and the edges of privacy curtains) are cleaned and/or disinfected more frequently than surfaces with minimal hand contact.

Disinfectant/detergent formulations registered by the EPA are used for environmental surface cleaning, but the most important step is the physical removal of microorganisms and soil by scrubbing and/or wiping.

A one-step process and an EPA-registered hospital disinfectant/detergent designed for general housekeeping purposes should be used in patient-care areas when:

- The nature of the soil on these surfaces is uncertain

- The presence or absent of multi-drug resistant organisms on such surfaces is uncertain

Follow facility policies and procedures for effective handling and use of mops, cloths, and solutions (CDC, 2019e).

CLEANING IMMUNOSUPPRESSED PATIENT AREAS

In areas where immunosuppressed patients are cared for, cleaning/disinfecting involves:

- Wet dusting of horizontal surfaces daily with cleaning cloths premoistened with detergent or an EPA-registered hospital detergent/disinfectant

- Avoiding the use of cleaning equipment or methods that disperse dust or produce mists or aerosol

- Equipping vacuums with HEPA filters

- Regular cleaning and maintenance of equipment to ensure efficient particle removal

- Closing the doors of immunocompromised patients’ rooms when vacuuming, waxing, or buffing corridor floors to minimize exposure to airborne dust

(CDC, 2019e)

CLEANING UP BLOOD SPILLS

All environmental and working surfaces must be promptly cleaned and decontaminated after contact with blood or OPIM. Protective gloves and other appropriate PPE should be worn, and an appropriate disinfectant should be used.

After putting on personal protective equipment:

- If the spill contains large amounts of blood or body fluids, clean the visible matter with disposable absorbent material, and discard in an appropriate, labeled container.

- Swab the area with a cloth or paper towels moderately wetted with disinfectant and allow the surface to dry.

- Use EPA-registered hospital disinfectants labeled tuberculocidal or registered germicides with specific label claims for HIV or HBV.

- Use an EPA-registered sodium hypochlorite product; if not available, general versions (e.g., household chlorine bleach) may be used.

- Use a 1:100 solution of hypochlorite product or chlorine bleach to decontaminate nonporous surfaces after cleaning a spill in patient-care settings.

(CDC, 2019e)

Reprocessing Healthcare Equipment and Devices

Depending on the intended use, reusable medical and surgical equipment and devices must undergo reprocessing that involves:

- Cleaning alone, for noncritical items

- Cleaning followed by disinfection, for semi-critical items

- Cleaning followed by sterilization, for critical items

| Classification/ Intended Use |

Goal of Process | Appropriate Process |

|---|---|---|

| (CDC, 2019e) | ||

| Non-critical items Objects that come into contact with intact skin but not mucous membranes, e.g.:

|

Clean of:

|

|

| Semi-critical items Items that make contact, directly or indirectly, with intact mucous membranes or nonintact skin, e.g.:

|

Free of all microorganisms, with exception of high numbers of bacterial spores |

|

| Critical items Items entering sterile tissue, body cavity, vascular system, nonintact mucous membranes, e.g., surgical instruments |

Free of all microorganisms, including bacterial spores |

|

CLEANING

Cleaning involves removal of foreign material (e.g., soil, organic material) from objects and is normally accomplished using water with detergents or enzymatic products. Thorough cleaning is required before high-level disinfection and sterilization because inorganic and organic material remaining on the surfaces of instruments interfere with the effectiveness of these process. If soiled materials dry or bake onto the instruments, the removal process becomes more difficult and the disinfection or sterilization process less effective or ineffective.

Perform either manual cleaning (using friction) or mechanical cleaning (using ultrasonic cleaners, washer-disinfector, or washer-sterilizer).

When a washer-disinfector is used, care should be taken in loading instruments: hinged instruments should be opened fully to allow adequate contact with the detergent solution; stacking of instruments in washers should be avoided; and instruments should be disassembled as much as possible.

There are no real-time tests that can be used in a clinical setting to verify cleaning. The only way to ensure adequate cleaning is to conduct a reprocessing verification test (e.g., microbiologic sampling), but this is not routinely recommended (CDC, 2019e).

DISINFECTION

Disinfection describes a process that eliminates many or all pathogenic microorganisms, except bacterial spores, on inanimate objects. In healthcare settings, objects usually are disinfected by liquid chemicals or wet pasteurization. Factors that can affect the effectiveness of either method include:

- Organic and inorganic load present

- Type and level of microbial contamination

- Concentrations of an exposure time to the germicide

- Physical natural of the object

- Presence of biofilm

- Temperature and pH of the disinfection process

- Relative humidity of the sterilization process

There are three levels of disinfection, as described in the table below.

| Level | Disinfection/Process |

|---|---|

| (CDC, 2019e) | |

| Low |

|

| Intermediate |

|

| High |

|

STERILIZATION

Sterilization destroys all microorganisms on the surface of an article or in a fluid to prevent disease transmission. Medical devices that have contact with sterile body tissues or fluids must be sterile when used. The use of inadequately sterilized items represents a high risk of transmitting pathogens; however, documented transmission of pathogens associated with an inadequately sterilized critical item is exceedingly rare.

FDA-approved sterilization methods are described in the table below.

| Sterilization Process | Description | Uses |

|---|---|---|

| (CDC, 2019e) | ||

| Steam under pressure (moist heat) |

|

|

| Flash steam |

|

|

| Low-temperature ethylene oxide (ETO) gas | Parameters:

|

|

| Hydrogen peroxide gas plasma | Inactivates microorganisms by the combined use of hydrogen peroxide gas and the generation of free radicals | High temperature– and humidity-intolerant materials and devices, including:

|

| Peracetic acid |

|

Medical and surgical instruments (e.g., endoscopes, arthroscopes) |

| Dry heat | Static or forced air penetrates material | Materials damaged by moist heat or impenetrable to moist heat (e.g., powders, sharp instruments, petroleum products) |

| Ozone | Created from:

|

Compatible with a wide range of commonly used materials and effective for rigid lumen devices |

MONITORING REPROCESSING EFFECTIVENESS

Effectiveness of reprocessing depends on:

- Thorough cleaning before either disinfection or sterilization

- Choice of the right disinfectant product

- Presence of organic matter (inadequate cleaning), which can inactivate many disinfectants

- Use of mechanical scrubbing. In general, biofilms are not readily removed by chemicals alone but require mechanical scrubbing. (Biofilms are constructed by some bacteria to protect themselves from hostile environments such as disinfectants. An example of a biofilm is the film on teeth in the morning, not removed by mouthwash, requiring brushing.)

Monitoring disinfection is essential to document the effectiveness of reprocessing. Factors to be documented include:

- Activity (concentration) of the disinfectant

- Contact time with internal and external components

- Recordkeeping and tracking of equipment usage and reprocessing

- Handling and storage after disinfection to prevent contamination

Monitoring sterilization involves maintaining records of each sterilizer load, routinely evaluating the sterilizing conditions, and indirectly evaluating the microbiological status of the processed items. This is accomplished by using a combination of mechanical, chemical, and biological indicators.

- Mechanical monitors for both steam sterilization and ETO sterilization provide data on cycle time, temperature, and pressure. However, two essential elements for ETO sterilization (gas and humidity) cannot be monitored in healthcare ETO sterilizers.

- Chemical indicators are affixed on the outside of each pack to indicate that the item has been exposed to the sterilization process. It does not, however, prove sterilization has been achieved. A chemical indicator should also be placed on the inside of each pack to verify sterilant penetration. Chemical indicators are either heat-or chemical-sensitive inks that change color when one or more sterilization parameters are present. Chemical indicators should be used in conjunction with biological indicators.

- Biological indicators are considered to be the closest to ideal because they measure the sterilization process directly by using a preparation of the most resistant pathogen (Bacillus spores) as an indicator of sterility. These preparations are added to a carrier and then packaged. Biological indicators specifically designed for monitoring flash sterilization are now available, and a new rapid-readout ETO biological indicator has been designed for rapid and reliable monitoring of the process.

Periodic infection control rounds to areas using sterilizers for the purpose of standardizing use may identify correctable variances in operator competence, documentation of sterilization records, sterilizer maintenance and wrapping, and load numbering of packs (CDC, 2019e).

PACKAGING, STORAGE, AND HANDLING OF PROCESSED ITEMS

Written and illustrated procedures for preparation of items to be packaged should be readily available and used by personnel when packing procedures are performed.

Once items are cleaned, dried, and inspected, those requiring sterilization must be wrapped or placed in rigid containers and arranged in instrument trays/baskets according to guidelines.

There are several choices in packaging methods to maintain sterility of surgical instruments, including:

- Rigid containers

- Peel-open pouches, (e.g., self-sealed or heat-sealed plastic and paper pouches)

- Roll stock or reels (i.e., paper-plastic combinations of tubing designed to allow the user to cut and seal the ends to form a pouch)

- Sterilization wraps (woven and nonwoven)

The packing material must:

- Allow penetration of the sterilant

- Provide protection against contamination during handling

- Provide an effective barrier to microbial penetration

- Maintain the sterility of the processed item after sterilization

Wrapped surgical trays remain sterile for varying periods depending on the type of material used to wrap the trays. Safe storage times for sterile packs vary with the porosity of the wrapper and storage conditions.

Heat-sealed, plastic peel-down pouches and wrapped packs sealed in 3 mil polyethylene overwrap have been reported to be sterile for as long as nine months after sterilization. The polyethylene is applied after sterilization to extend the shelf life for infrequently used items. Supplies wrapped in double-thickness muslin comprising four layers remain sterile for at least 30 days.

Any sterilized item should not be used after the expiration date has been exceeded or if the sterilized package is wet, torn, or punctured. Although some hospitals continue to date every sterilized product and use the time-related shelf-life practice, many hospitals have switched to an event-related practice. This practice recognizes that the product should remain sterile until some event causes it to become contaminated (e.g., tear in packaging, packaging becomes wet, or seal is broken).

Following the sterilization process, handling of medical and surgical devices must use aseptic technique in order to prevent contamination (CDC, 2019e).

REPROCESSING AND REUSE OF SINGLE-USE DEVICES

Reusing single-use medical devices (SUDs) has been occurring since the late 1970s. Single-use medical devices can be reprocessed within healthcare organizations or by outside vendors (third-party reprocessors). Specifically, the FDA requires third-party reprocessors to meet the same criteria for the reprocessed devices as the original equipment manufacturer.

The FDA (2020) is proposing to prioritize its enforcement of premarket requirements for reprocessed SUDs on the basis of the risk that is likely to be posed by the reuse of the device.

The public health risk presented by a reprocessed SUD varies. Some that are low risk when used only one time may present an increased risk to a patient upon reprocessing. Others that are low risk when used for the first time may remain low risk after reprocessing, provided the reprocessor conducts cleaning and sterilization/disinfection in the appropriate manner.

CASE

Jennifer is a nurse and manager of an outpatient procedure center that performs colonoscopies and endoscopies on a regular basis. In the past three months, the center has had reports of six patients with a diagnosis of a strain of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) Escherichia coli (E. coli) that occurred within a few weeks of their GI procedures. An investigation was initiated by public health authorities to identify the source and prevent further transmission to other patients.

The investigators worked with Jennifer and the center to review the histories of all patients. They discovered that each patient had undergone a similar invasive procedure using an endoscope. On reviewing the center’s procedures, public health investigators found that the center has been cleaning and reprocessing the endoscopes according to manufacturer-recommended procedures for disinfecting. However, one endoscope was cultured and found to contain the resistant strain of E. coli.

Investigators recommended to Jennifer and the center that they switch to a liquid chemical, high-level disinfection system appropriate to their endoscope inventory and monitor the effectiveness by following the recommendations of the manufacturers of both the disinfection system and the endoscopes.

Jennifer and her instrument processing personnel met with their counterparts and an infection preventionist at the hospital with whom their physicians have privileges. Using the expertise and experience of their colleagues, they made recommendations to the management team of their procedure center regarding equipment acquisitions and policy/procedure changes.

After the center changed its disinfection procedures, no additional cases of E. coli occurred and patient safety has been maintained. The center invested a significant amount of its capital improvement and inventory budgets to purchase and install the disinfection system and acquire additional endoscopes and accessory instruments because of this outbreak.

Waste Management

Treatment of regulated medical waste reduces the microbial load in or on the waste and renders the by-products safe for further handling and disposal. Regulated medical waste treatment methods include:

- Chemical disinfection

- Grinding/shredding/disinfection methods

- Energy-based technologies (e.g., microwave, radio wave treatments)

- Disinfection/encapsulation methods

Medical wastes require careful disposal and containment. OSHA requirements are designed to protect workers who generate medical waste and who manage the wastes from point of generation to disposal. Personnel responsible for waste management must receive appropriate training in handling and disposal methods in accordance with facility policy.

State medical waste regulations specify appropriate treatment for each category of regulated waste. Major categories of medical waste requiring special handling and disposal precautions include:

- Microbiology laboratory wastes (e.g., cultures and stocks of microorganisms)

- Bulk blood, blood products, blood, and bloody body fluid specimens

- Pathology and anatomy waste

- Sharps (e.g., needles and scalpels)

Of all the categories of regulated medical waste, microbiologic wastes pose the greatest potential for infectious disease transmission, and sharps pose the greatest risk for injuries.

CONTAINERS AND DISPOSAL METHODS

In addition to any state rules for disposing of regulated waste, OSHA rules state that regulated waste must be placed in containers that are:

- Closable

- Constructed to contain all contents and prevent leakage of fluids during handling, storage, transport, or shipping

- Labeled or color-coded

- Closed prior to removal to prevent spillage or protrusion of contents during handling, storage, transport, or shipping

If outside contamination of the regulated waste container occurs, it must be placed in a second container meeting the above standards.

Sharps containers must be puncture-resistant and located as close as possible to point of use. The container must be labeled with the universal biohazard symbol and the word biohazard or be color-coded red. Sharps containers must be maintained upright throughout use, replaced routinely, and not be allowed to overfill. Also, containers must be:

- Capable of maintaining impermeability after waste treatment

- Closed immediately prior to removal or replacement to prevent spillage or protrusion of contents during handling, storage, transport, or shipping

- Placed in a secondary container if leakage is possible; the second container must be:

- Closeable

- Constructed to contain all contents and prevent leakage during handling, storage, transport, or shipping

- Labeled or color-coded

- Reusable containers must not be opened, emptied, or cleaned manually or in any other manner that would expose employees to risk of percutaneous injury

- Upon closure, duct tape may be used to secure the lid of a sharps container as long as the tape does not serve as the lid itself.

CDC recommendations state:

- On-site incineration is an option for microbiologic, pathologic, and anatomic waste.

- Waste generated in isolation areas should be handled using the same methods used for waste from other patient-care areas.

- Containers with small amounts of blood remaining after laboratory procedures, suction fluids, or bulk blood can either be inactivated or carefully poured down a utility sink drain or toilet. No evidence indicates that bloodborne diseases have been transmitted from contact with raw or treated sewage.

- If treatment options are not available at the site of waste generation, transport in closed, impervious containers to the on-site treatment location or to another facility for treatment as appropriate.

- Store regulated medical wastes awaiting treatment in a properly ventilated area inaccessible to vertebrate pests. Use waste containers that prevent development of noxious odors.

- Regulated waste that has been decontaminated need not be labeled or color-coded.

(CDC, 2019e)

WARNING LABELS

Warning labels that include the universal biohazard symbol, followed by the term “biohazard,” must be included on:

- Bags and containers of regulated waste

- Refrigerators and freezers containing blood or OPIM

- Other containers used to transport or ship blood or OPIM

- Contaminated equipment that is to be serviced or shipped (must also contain a statement relating to which portions of the equipment remain contaminated)

These labels are fluorescent orange, red, or orange-red. Bags used to dispose of regulated waste must be red or orange-red, and they too must have the biohazard symbol in a contrasting color readily visible upon them.

Red bags or red containers may be substituted for the biohazard labels.

Biohazard warning label. (Source: OSHA.)

Linens and Laundry Management

The risk of actual disease transmission from soiled laundry is negligible. However, the hands of healthcare workers may be contaminated by contact with patient bed linens. Thus, common sense hygienic practices for handling, processing, and storage of textiles are recommended. These practices include:

- Do not shake items or handle them in any way that may aerosolize the infectious agents.

- Avoid contact of one’s own body and personal clothing with the soiled items being handled.

- Wear gloves and other protective equipment, as appropriate, when handling contaminated laundry.

- Contain soiled items in a laundry bag or designated bin at the location where they were used, minimizing leakage.

- Do not sort or rinse textiles in the location of use.

- Label or color-code bags or containers for contaminated waste.

- If laundry chutes are used:

- Ensure that laundry bags are securely closed before they are placed in the chute.

- Do not place loose items in the laundry chute.

- For textiles heavily contaminated with blood or other body fluids, bag and transport in a manner that will prevent leakage.

- Do not use dry cleaning for routine laundering in healthcare facilities.

- For clean textiles, handle, transport, and store by methods that will ensure their cleanliness.

- If healthcare facilities require the use of uniforms, they should either make provisions to launder them or provide information to the employee regarding infection control and cleaning guidelines for the item based on the tasks being performed at the facility.

(CDC, 2019e)

OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard requires employers to ensure that employees who have contact with contaminated laundry wear protective gloves and other appropriate PPE.

Employers are responsible for laundering reusable PPE. Work clothes such as uniforms are not considered to be PPE. Provided gowns or other PPE should be used to prevent soiling of uniforms.

Training healthcare workers who are responsible for housekeeping and management of linen and waste in appropriate infection control for their particular duties is essential for safe patient care.

CASE

David is a charge nurse in the emergency department (ED) in a rural hospital and is working with a team caring for a trauma patient, a farmer who was transported after an accident involving harvesting equipment. The patient is bleeding out from a partially severed arm on arrival, and the ED team stabilizes the patient prior to transfer to the OR.

Once the patient is transferred to the OR, David returns to the ED to work with housekeeping to ensure proper cleanup of the room. The housekeeping team has had the required infection control training but has had little experience with this type of trauma cleanup. Cleaning this room is doubly complex for them: There is the sheer volume and complexity of the work itself and the unavoidable thoughts about what caused it. As the charge nurse on duty, David is responsible for supervising the team and ensuring that proper procedure is followed.

David confirms that the housekeeping team has donned appropriate PPE prior to starting cleanup. Surfaces contaminated with blood are first cleaned with recommended disinfectant. All soiled items are contained, placed in biohazard bags, and secured for disposal. David also takes a second look to make sure that any sharps are placed in sharps containers and secured for disposal. Laundry that is contaminated with blood is also secured according to hospital procedures.

After cleanup, PPE is removed and discarded by the team in biohazard bags. Each team member monitors their uniform for any soiled items and performs hand hygiene as a final step prior to moving on to the next work assignment.

Because David considers the housekeeping personnel part of the team involved in this patient’s care, he coordinates with his manager to ensure that they are offered the same postincident care as those directly involved.