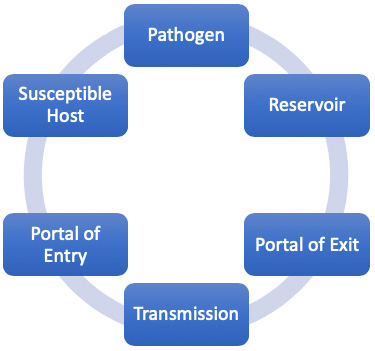

THE CHAIN OF INFECTION

Epidemiology involves knowing how disease spreads and how it can be controlled. Infection can only spread when conditions are right. This set of conditions is referred to as the “chain of infection,” which consists of six links. When all the links are connected, infection spreads. Infection control and prevention training provides the knowledge and skills that healthcare professionals can use to break the links in the chain and prevent the occurrence of new infections. Thus, understanding the chain of infection is at the foundation of infection prevention (APIC, 2020).

The six links in the chain of infection.

(Source: Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc.)

| Link | Examples |

|---|---|

| (Genieieiop, 2017) | |

| 1. Pathogen: Micro-organisms capable of causing disease or illness |

|

| 2. Reservoir: Places in which infectious agents live, grow, and reproduce |

|

| 3. Portal of exit: Ways in which an infectious agent leaves the reservoir |

|

| 4. Transmission: Ways in which the infectious agent is spread from reservoir to susceptible host |

|

| 5. Portal of entry: Ways in which the infectious agent enters the susceptible host |

|

| 6. Susceptible host: Individuals with traits that affect their susceptibility and severity of disease |

|

Pathogens

A pathogen is any biological agent that can cause disease or illness in its host.

BACTERIA

Bacteria are single-celled organisms present everywhere, some of which can cause disease. Humans are host to numerous bacteria—referred to as “normal flora” or “resident bacteria.” These usually do not cause disease unless their balance is disturbed or they are moved to a part of the body where they do not belong or to a new susceptible host. Important bacteria causing human disease include:

- E. coli (urinary tract infection, diarrhea)

- Streptococci (wound infection, sepsis, death)

- Clostridioides difficile (severe diarrhea, colitis, death)

- Mycobacterium (tuberculosis)

- Staphylococcus (skin boils, pneumonia, endocarditis, sepsis, death)

- Chlamydia trachomatis (sexually transmitted disease)

- Pseudomonas (infections in any part of the body)

- Rickettsia (spotted fever, typhus)

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae (“walking pneumonia”)

Bacterial spores (endospores) are thick-walled cells formed by bacteria to preserve the cell’s genetic material when conditions exist that are not conducive to bacterial growth and reproduction. This allows them to remain in a dormant state until conditions for multiplying return. Endospores can survive for extreme lengths of time. Most types of bacteria cannot change to the endospore form. Examples of bacteria capable of forming endospores include Bacillus and Clostridium. Bacterial spores are resistant to disinfectant and drying conditions. Infectious diseases transmitted to humans by endospores include:

- Anthrax

- Tetanus

- Gas gangrene

- Botulism

- Pseudomembranous colitis

(OSU, 2020)

VIRUSES

Viruses are not considered living organisms because they are acellular, i.e., they do not consist of cells. They contain either an RNA or DNA genome surrounded by a protective protein coat, and they lack the metabolic and biosynthetic machinery to reproduce. For this reason, they must co-opt a host’s cellular mechanisms in order to multiple and infect other hosts. Viruses can infect every type of host cell, but typically they infect only specific cell types within a host.

Viruses can be transmitted through direct contact, indirect contact with fomites, or through a vector (another living entity, such as a tick or mosquito). There are a wide variety of viruses that cause infections and disease. Some of the deadliest emerging pathogens in humans are viruses; however, we have few treatments or drugs to deal with them. Some of the more common diseases caused by viruses include:

- COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2)

- Chicken pox (varicella)

- Common cold (200+ types of rhinoviruses)

- Croup (parainfluenza virus)

- Ebola (Ebolavirus)

- Influenza (influenza A, B, and C viruses)

- Mumps (paramyxovirus)

- Polio (poliovirus)

- German measles (rubella virus)

- Rabies (rabies virus)

- HIV (human immunodeficiency viruses)

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV)

(OSU, 2020)

FUNGI

Fungi are prevalent throughout the world, but only a few cause disease in healthy people. Fungi are most closely related to animals and more distantly to plants. Fungi can be single cells or very complex multicellular organisms. Fungi can occur as yeasts, molds, or as a combination of both forms, some of which can cause superficial, cutaneous, subcutaneous, systemic, or allergic diseases.

In humans, most fungi affect skin, nails, and superficial mucosa. These are commonly caused by a group of at least 40 species of fungi called dermatophytes, but they can also be caused by common molds such as Aspergillus and the yeast Candida albicans. In persons with weakened immune systems, Candida can cause life-threatening invasive bloodstream or systemic infections.

Candida auris is an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat because it is often multidrug-resistant; it is difficult to identify with standard laboratory methods; and it has caused outbreaks in healthcare settings, including bloodstream, wound, and ear infections (MS, 2020; CDC, 2020e).

PRIONS

A prion is a nonliving disease agent similar to a virus in that it is unable to self-propagate. A prion is a misfolded rogue form of normal protein found in the cells. This prion protein may be caused by a genetic mutation, or it may occur spontaneously and can stimulate other endogenous normal proteins to become misfolded also, forming plaques.

Prions are known to cause various forms of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy in humans (Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease) and animals (mad cow disease, chronic wasting disease in elk and deer). They are extremely difficult to destroy because they are resistant to heat, chemicals, and radiation (OSU, 2020).

PROTOZOA (PROTISTS)

Protozoa are single-celled microorganisms that are larger than bacteria. They are neither plants, animals, nor fungi. They are very diverse, some being free-living, others parasitic. Most are harmless, but some can cause disease in animals and humans. Examples of diseases caused by protozoa include:

- Severe diarrhea (Giardia lamblia)

- Sleeping sickness (Trypanosoma)

- Malaria (Plasmodium protozoa)

- Pneumonia (Pneumocystis carinii)

- Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (Naegleria)

- Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii)

In individuals with weakened immune systems, untreated toxoplasmosis can lead to seizures and life-threatening illness such as encephalitis, which is fatal in those with AIDS (OSU, 2020).

Protozoa that live in a human’s intestine are transmitted through the fecal-oral route, and those that live in the blood or tissue are transmitted by arthropod vectors (e.g., mosquitoes) (CDC, 2020f).

HELMINTHS

Helminths are large, multicellular organisms that are generally visible to the naked eye in their adult states. They infect humans primarily through ingestion of eggs or when the larvae penetrate the skin or mucous membranes. These organisms can cause anemia, chronic pain, diarrhea, and undernutrition. There are four main groups of helminths that are human parasites:

- Flatworms (platyhelminths) (include flukes and tapeworms)

- Thorny-headed worms (acanthocephalins)

- Roundworms (nematodes) (immature/larval states can cause infection of various body tissues)

- Hookworms (Necator americanus)

(CDC, 2020f)

Reservoirs

The next link in the chain of infection is the reservoir, the usual “habitat” in which the infectious agent (pathogen) lives and multiplies. It is defined as any person, animal, arthropod, plant, soil, substance, or a combination of these on which it depends primarily for survival and where it reproduces itself in such a way that it can be transmitted to a susceptible host.

A reservoir, however, is not the same thing as the “source.” For example, in typhoid fever, the reservoir may be a person with the infection, but the source of infection may be the feces or urine of those who are infected or contaminated food, milk, or water (Aryal, 2020).

HUMAN RESERVOIRS

The most important reservoir of infection for humans are other humans, and humans are also the most important reservoir for healthcare-associated infections. The nose (nostrils, nares) may harbor bacteria and viruses. The skin is another natural reservoir for yeast and bacteria, and both healthcare workers and patients may carry pathogenic MRSA and Staphylococcus on their skin. The gastrointestinal tract is a reservoir for many different types of organisms, including viruses, bacteria, bacterial spores, and parasites.

People who are sick can release microbes into the environment through infected body fluids and substances. For example, sneezing releases influenza virus in secretions from the respiratory tract. Coughing releases tuberculosis bacteria from the lungs. Diarrhea releases C. difficile and many pathogens from the bowel. Exudates from skin lesions release Staphylococcus in pus from boils or herpes virus from fluid in sores around the mouth, hands, or other body areas.

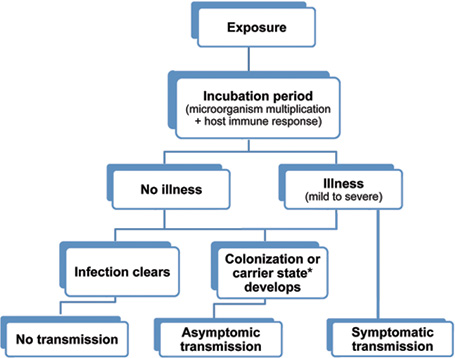

Two types of human or animal reservoirs are generally recognized. These are (1) symptomatic persons who have a disease (cases) and (2) carriers who are asymptomatic and can still transmit the disease. Carriers are individuals who have been colonized by a pathogen. Colonization is the presence of a microorganism on or in a host with growth and multiplication of the organism but no clinical expression or immune response from the host.

There are five types of carriers:

- Healthy or passive carrier: A person exposed to and harboring a pathogen but who has not become ill or has no symptoms

- Active carrier: A person who has been exposed to and harbors a pathogen, even though the person may have recovered from the disease

- Incubatory carrier: A person exposed to and harboring a pathogen in the beginning stages of the disease (e.g., the incubation period for HIV can last for many years before symptoms occur, but the person is able to transmit HIV to others during that time period)

- Intermittent carrier: A person exposed to and harboring a pathogen who can spread the disease in different places or at different intervals

- Convalescent carrier: A person who harbors the pathogen and, although in the recovery phase, is still infectious

(Merrill, 2021)

The important point to remember is that infectious agents are transmitted every day from people who are sick as well as from those who appear to be healthy. In fact, those individuals who are carriers may present more risk for disease transmission than those who are sick because:

- They are not aware of their infection.

- Their contacts are not aware of their infection.

- Their activities are not restricted by illness.

- They do not have symptoms and, therefore, do not seek treatment.

Possible outcomes of exposure to an infectious agent. (Source: Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc.)

* The term carrier state is used to describe the presence of a microorganism on or in a host with growth and multiplication of the organism but no clinical expression or immune response from the host.

ANIMAL/INSECT RESERVOIRS

Animal reservoirs transmit infectious diseases from animal to animal, with humans as incidental hosts. An infectious disease caused by a pathogen transmitted from birds, rodents, reptiles, amphibians, insects, and other domestic and wild animals is called a zoonosis. A common way for these pathogens to spread are via a vector, usually a bite from a mosquito, mite, or tick. Examples of zoonoses include:

- Rabies (from bats, skunks, raccoons, and other mammals, transmitted directly through a bite)

- SARS (believed to originate from horseshoe bats that transmitted the virus to small mammals called civets, which are trapped and eaten, exposing humans to blood or organs during butchering or food preparation; now capable of being transmitted from human to human in respiratory secretions)

- Lyme disease (from deer mice to deer ticks to humans)

- Bubonic plaque (from rats or prairie dogs to fleas to humans)

- West Nile virus (from birds to mosquito to humans)

- Zika (from monkeys to domestic animals and humans)

- Scabies (mites transmitted from humans to humans)

(Merrill, 2021)

ENVIRONMENTAL RESERVOIRS

Environmental reservoirs are certain environmental conditions or substances (e.g., food, feces, decaying organic matter) that are conducive to the growth of pathogens. Pathogens may survive in such a reservoir but may or may not multiply or cause disease. These reservoirs can include soil, water, and air, as well as inanimate objects, referred to as fomites, that convey infection because they have been contaminated by pathogenic organisms. Examples include facial tissues, doorknobs, telephones, bed linens, toilet seats, and clothing.

Environmental reservoirs in healthcare facilities can include:

- Contaminated medical devices (e.g., central venous catheters, urinary catheters, endoscopes, surgical instruments, ventilators, needles/sharps)

- Contaminated water sources

- Contaminated medications

- Air from heating, ventilation, or air conditioning systems

- Hospital textiles (e.g., linens, privacy curtains)

- Patient care equipment (BP cuffs, gloves)

(Christenson & Fagan, 2018)

Portal of Exit

The portal of exit is the route (or routes) by which a pathogen leaves the reservoir.

| Portal | How the Pathogen Exits | Infectious Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| (CDC, 2019b) | ||

| Respiratory tract | Coughing, sneezing | Influenza, tuberculosis, common cold, SARS, COVID-19 |

| Skin | Draining skin lesions or wounds | Scabies, staph infection, MRSA |

| Blood | Insect bite, needles, syringes | HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B, hepatitis C |

| Digestive tract | Feces, saliva | Hepatitis A, cholera, salmonella infection, parasites, typhoid |

| Genitourinary tract | Urine, semen, vaginal secretions | HIV/AIDS, herpes, cytomegalovirus |

| Placenta | Mother to fetus | Herpes, malaria, rubella, Zika* |

| * The Zika virus has been found to cross the maternal-fetal barrier in the placenta, which viruses normally cannot do, and to infect the fetus, resulting in the birth defect microencephaly (small head with incomplete brain development). | ||

Modes of Transmission

In order for an organism to travel from one person to another or from one place in the body to another, it must have a way of getting there, or a mode of transmission. For any single agent, there are often many different means by which it can be transmitted. The modes of HAI transmission include:

Contact transmission, the most important and frequent mode of HAI transmission, is divided into three subgroups: direct contact, indirect contact, and droplet.

- Direct contact transmission involves skin-to-skin direct contact and the physical transfer of pathogens between a susceptible host and an infected or colonized person. Examples include scabies, sexually transmitted diseases, mononucleosis, and MRSA. Direct contact can include:

- Childbirth

- Medical procedures

- Injections of drugs

- Airborne, propelled a short distance (3–6 feet) via droplets, coughing, or sneezing and deposited on the host’s conjunctivae, nasal mucosa, or mouth

- Transfusion (blood)

- Transplacental

- Indirect contact transmission occurs by:

- Vehicle transmission involves contact of a susceptible host with a contaminated inanimate object (fomite), such as food, water, medications, contaminated instruments, patient-care equipment, needles, dressings, gloves, or hands. Contaminated hands are often responsible for transmission of HAIs.

- Vector-borne transmission usually refers to insects; however, a vector can be any living creature that transmits an infectious agent to humans. Vector-borne transmission is not a common source of HAIs.

- Airborne, long-distance transmission involves generation of aerosolized particles from droplet nuclei that remain infectious when suspended in air over long distances and time. Aerosolized particles may also be generated from biological waste products.

(Ather et al., 2020)

The mode of transmission is the weakest link in the chain of infection, and it is the only link that healthcare providers can hope to eliminate entirely. Therefore, a great many infection control efforts are aimed at avoiding carrying pathogens from the reservoir to the susceptible host.

Because people touch so many things with their hands, hand hygiene is still the single most important strategy for preventing the spread of infection.

HIGH-RISK SETTINGS FOR INFECTION TRANSMISSION

Every area of the healthcare facility and every type of patient care holds the potential for exposure to pathogens, but some settings and practices present greater risk than others. High-risk settings include:

- Intensive care units

- Burn units

- Pediatric units and newborn nurseries

- Operating rooms

- Long-term care facilities

Transmission risks within the various healthcare settings are influenced by the characteristics of the population (e.g., immunocompromised patients, exposure to indwelling devices and procedures), intensity of care, exposure to environmental sources, length of stay, and interaction among and between other patients as well as healthcare providers.

Intensive Care Units

More than 20% of all HAIs are acquired in ICUs. In an international study, 60% of ICU patients were considered infected, and the risks of infection in general and with a resistant pathogen in particular increased with the length of stay. Infections and sepsis are the leading cause of death in noncardiac ICUs and account for 40% of all ICU expenditures. The most important HAIs are catheter-related bloodstream infections, ventilator-associated pneumonias, and catheter-associated urinary tract infections.

Risk factors for HAIs in ICU patients include:

- Chronic comorbid illnesses such as diabetes, predisposing to colonization and infections by MDROs

- Immunosuppression

- Frequent presence of invasive devices

- High frequency of invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures

- Presence of traumatic injuries and/or burns

- Age (older adults and neonates being more susceptible to infection)

- Frequent manipulations and contact with healthcare workers who are concurrently caring for multiple ICU patients

- Longer lengths of stay

- Colonization pressure (the proportion of patients colonized with a particular organism in a defined geographic area within a hospital during a specified time period)

(Marchaim & Kaye, 2020)

Burn Units

The incidence rate of infections in burn units has been found to be 21.8 events per 1,000 patient-days. Burn patients are at higher risk for many types of infections because of the loss of skin barrier and immunosuppression that occurs as a result of systemic inflammatory response due to injured tissue (Escandón-Vargas et al., 2020). Burn wound infections are often the source of systemic infections, including bloodstream infections and pneumonia, which can result in sepsis, multisystem organ failure, and death.

Hydrotherapy equipment is an important environmental reservoir, and its use is discouraged. Advances in burn care—specifically early excision and grafting of the burn wound, use of topical antimicrobial agents, and institution of early enteral feeding—have led to decreased infections, but no studies exist that define the most effective combination of infection control precautions for use in burn settings (Siegel et al., 2019).

Patients in burn units have additional risk factors for developing infections:

- Comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes

- Presence of invasive devices

- Large burn areas

- Full-thickness burns

- Inhalation injury

(Strassle et al., 2017)

Newborn Nurseries and Pediatric Units

Pediatric intensive care unit patients and those with lowest birthweight have high rates of central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infections. There is a high prevalence of community-acquired infections among hospitalized infants and young children who have not yet become immune either by vaccination or by natural infection.

Close physical contact between healthcare personnel and infants and children offers many opportunities for transmission of infectious material. Children congregating in play areas with toys where bodily secretions are easily shared and family members rooming in can further increase risk of transmission (Siegel et al., 2019).

Other risk factors for infection in young patients include:

- Gestational age

- Low birth weight

- Age

- Presence of single or multiple invasive devices

- Invasive interventions and medical treatments

- Insufficient immune system development

- Insufficient mechanical barriers

- Lack of protective flora

- Permeable skin

- Parenteral nutrition

(Nandy, 2019)

Operating Rooms

This setting places both the patient and provider at higher risk for transmission of infectious pathogens. Factors that increase risk include:

- Invasive procedures with instruments (scalpel and other sharps) and tissue and blood exposure

- Quality of ventilation system

- Number of people present and their movements

- Rate of door opening

- Duration of surgery

- Classification of intervention as “dirty” (e.g., exposure to fecal material)

(Alfonso-Sanchez et al., 2017)

Long-Term Care Settings

Patients in these settings are at increased transmission risk due to:

- Advanced age

- Decreased immunity

- Underlying chronic diseases

- Decreased mobility

- Urinary catheter use

- Recent hospitalization

- Previous antibiotic use

- Colonization with multidrug-resistant pathogens

(Richards & Stuart, 2018)

Portals of Entry

The term portal of entry refers to the anatomical route or routes by which a pathogen gains entry into a susceptible host. The portal of entry is often the same as the portal of exit from the reservoir.

| Portal | How the Pathogen Enters | Infectious Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | Conjunctivae, hair follicles, sweat ducts, cuts, nicks, abrasions, punctures, insect bites | Hookworm, tinea pedis, herpes simplex, folliculitis, sepsis |

| Respiratory tract | Inhalation | Influenza, tuberculosis, common cold, coronaviruses |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Food, drink, contaminated fingers | Diarrheal illnesses, salmonella infection, gastric and duodenal ulcers, gastroenteritis |

| Genitourinary tract | Skin or mucous membrane of penis, vagina, cervix, urethra, external genitalia | Cystitis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, genital herpes, HPV, HIV/AIDS |

| Across placenta to fetus | Vascular access | Zika, rubella, syphilis |

Medical and surgical procedures often introduce new portals or facilitate the entry of pathogens. Examples include IV catheters, surgical wounds, urinary catheters, endotracheal tubes, and percutaneous injuries. Healthcare workers may develop dermatitis from frequent handwashing or allergy to latex gloves. They may receive needlestick injuries that allow pathogens access to their bloodstream. Any invasive procedure may facilitate entry of pathogens into the host.

INVASIVE DEVICES

An invasive device provides a portal of entry for pathogens. It is a device that, in whole or part, penetrates inside the body either through a body orifice or through the body surface. Examples include:

- Vascular access devices

- Urinary catheters

- Wound drains

- Gastrostomy tubes

- Endotracheal tubes or tracheostomy

- Fracture fixation devices

- Traction pins

- Dental implants

- Joint prostheses

- Cardiac pacemakers

- Mammary implants

- Mechanical heart values

- Penile implants

Susceptible Host

The final link in the chain of infection is the susceptible host. In healthcare settings, susceptible hosts abound. Susceptibility to infections depends on the genetic or constitutional factors, physiologic and immunological condition of the host, and the virulence of the pathogen. Host factors that influence the outcome of an exposure include the presence or absence of natural barriers, the functional state of the immune system, and the presence or absence of an invasive device.

HOST NATURAL BARRIERS

There are many natural barriers against the penetration of pathogens into the human host. They are categorized as physical, mechanical, chemical, and cellular.

Three “Lines of Defense”

The first line of defense against the entry of pathogens includes physical, mechanical, and chemical barriers, which are considered functions of innate (natural or inborn) immunity.

- Physical barriers (or anatomical barriers) include the skin and associated accessories, such as nails and hair within the nose.

- Mechanical barriers include the eyelashes and eyebrows, cilia (tiny hairs in the respiratory tract), eyelids, and intact skin-mucous membranes. Coughing, sneezing, urinating, defecating, and vomiting are also mechanical barriers.

- Chemical barriers include tears, perspiration, sebum (oily substance produced by the skin), mucus, saliva, earwax, gastrointestinal secretions, and vaginal secretions. Tears contain active enzymes that attack bacteria. Mucus in the respiratory tract traps pathogens and contains enzymes that serve as antibiotics. The gastrointestinal tract contains various chemicals, including acid in the stomach, bile, and pancreatic secretions. The normal acidic environment of the vagina protects from most pathogens.

The second line of defense comes into play when pathogens make it past the first line. Cellular defensive processes include:

- Phagocytes. Two types of white blood cells, macrophages and neutrophils, destroy and ingest pathogens that enter the body.

- Inflammation. Several types of white blood cells flood a localized area that has been invaded by pathogens, allowing for the removal of damaged and dead cells and beginning the repair process.

- Fever. Elevated temperature inhibits the growth, and is even lethal, to some bacteria and viruses; it also facilitates the host’s immune response and increases the rate of tissue repair.

- Lymphatic system. Lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils, and adenoids collect and filter tissue fluids of harmful pathogens.

The third line of defense against invading pathogens is the immune system response, which involves lymphocytes.

- T cells send out an alarm and cause white blood cells to divide and multiply.

- B cells secrete antibodies that stick to antigens on the surface of pathogens and destroy them.

- Memory T and B cells store information about the invading pathogen to be used against a future invasion.

(Lindh et al., 2018)

The protective antibodies resulting from this process can be the result of:

- Past infection

- Vaccination or toxoid

- Indirectly through the placenta from mother to child

- Administration of antitoxin or immunoglobulin

Factors Affecting a Host’s Natural Barriers

Several important factors affect a host’s susceptibility to infection:

- Age. The very young and the very old are more susceptible to infection. The older adult often has comorbid conditions such as diabetes, renal insufficiency, or a decrease in immune function, and the young do not as yet have an immune system as efficient as adults.

- Genetics. Genetic background causes variations in innate immunity, e.g., Alaska Natives, Native Americans, and Asians are more susceptible to tuberculosis.

- Stress level. Stress increases the release of cortisol from the adrenal cortex, causing a suppression of the inflammatory response, which facilitates infection.

- Nutritional status. The function of the cells that make up the first, second, and third lines of defense are dependent upon specific nutrients without which the system weakens.

- Current medical therapy. Patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation are more susceptible to infections since these agents also destroy cells that make up the immune system. Transplant patients on immunosuppressant medications to prevent rejection are also more susceptible, as are patients taking corticosteroids.

- Pre-existing disease. Patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes or AIDS are more susceptible.

- Gender. Anatomical differences of the genitourinary tract allow bacteria to more easily traverse the shorter female urethra to reach the bladder.

(Paustian, 2017)

INFECTIOUS AGENT FACTORS

It is only when a pathogen has been successful in establishing a site of infection in the host that disease occurs, and little damage will result if the pathogen is unable to spread to other parts of the body. There are a number of factors that are important in this process.

Specific to the pathogen itself are its:

- Infectivity, or the ability of an infectious agent to invade and replicate in a host

- Pathogenicity, or the capacity of the agent to cause disease

- Virulence, or the extent of disease that the pathogen can cause

Another important factor includes the number of organisms that are transferred to the host (the inoculum). Some organisms require only a few to cause disease while others require many. The route of exposure, or the portal of entry of the pathogen, also influences the ability to cause infection, as does the duration or amount of time the host is exposed to the pathogenic reservoir.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Environmental factors are those extrinsic elements that affect the infectious agent and the opportunity for exposure. In a healthcare setting, these factors involve contamination of the environment and equipment.

Environmental contamination involves inanimate objects (fomites) such as air, water, food supply, floors, and surfaces around patients. Proper sanitation prevents the spread of infectious organisms from the environment to patients.

Contamination of equipment occurs when it is not cleaned and disinfected between patients. Equipment that has been contaminated can spread infectious agents from patient to patient.

CASE

Robert Turner, an 80-year-old patient, was admitted to the general medical unit for treatment of a pressure injury on his sacrum and the onset of new delirium and urinary incontinence. To protect the healing injury from urine, the medical team ordered placement of an indwelling urinary catheter. Mr. Turner is a susceptible host at risk of infection because of his advanced age, the fact that he is in the hospital, and because of the indwelling urinary catheter.

During the first three days of Mr. Turner’s hospital stay, the medical assessment revealed that a new medication was causing his delirium. The medication was stopped on the third day, and on the fifth day his delirium began to decrease. He slowly began to participate in activities of daily living. It was decided, however, to leave the indwelling urinary catheter in place until his pressure injury had sufficiently begun healing.

On day seven, his nurse noticed an abrupt change in the patient. He was more confused, agitated, and felt warm to the touch. On assessment, his temperature was 100.5 °F and he was slightly hypotensive. The medical team suspected the cause most probably was a urinary tract infection, and the urinary catheter was removed. Cultures confirmed infection with E. coli. Mr. Turner was started on antibiotics and IV fluids and recovered over the next three days.