HYPERGLYCEMIA-RELATED ILLNESSES AND COMPLICATIONS

People with diabetes face both acute and chronic health threats. Acute complications include diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. (Another possible emergency—hypoglycemia—is discussed above under “Insulin Therapy.”) Diabetes also continually injures tissues microscopically, and as these microscopic injuries accumulate, they lead to observable chronic problems such as heart disease or kidney failure.

Acute Complications

Before the discovery of insulin, most people with diabetes died of a condition known as diabetic coma, which came on suddenly and was fatal by the second or third day. Typically, this fatal condition was characterized by dehydration and precipitated by the occurrence of some other disease. Today, diabetic coma is called diabetic ketoacidosis.

Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (also called hyperosmotic hyperglycemic nonketotic state) are two emergency conditions that threaten persons with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Both conditions involve a high level of blood glucose that leads to dehydration beyond the body’s ability to cope. The person becomes tired and weak, is thirsty and urinates excessively, and often has an altered mental state, ranging from confusion to coma. Dehydration causes hypotension and acute renal failure, and if not treated with IV fluids and insulin, the condition leads to serious electrolyte abnormalities, brain injury, and death.

DIABETIC KETOACIDOSIS

Diabetic ketoacidosis develops when there is so little insulin that the body begins to use fat as a major fuel. Diabetic ketoacidosis is seen primarily in people with type 1 diabetes, although some people with type 2 diabetes may develop the condition.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is characterized by acidic ketones (the result of fat metabolism) in the blood and urine, and ketones can be smelled on the patient’s breath, giving a fruity or acetone-like odor. The resulting acidosis—a drop in blood pH below 7.3 (normal pH is 7.38 to 7.44)—causes the body to adopt a deep, sighing pattern of respiration called Kussmaul breathing or air hunger. Diabetic ketoacidosis, which usually comes on quickly (within a day or two), also produces nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain (Nettina, 2019).

HYPEROSMOLAR HYPERGLYCEMIC STATE

Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) develops when there is sufficient insulin for the body to use glucose as a fuel but there is not enough insulin to keep blood glucose levels in a safe range. HHS is primarily seen in older adults with type 2 diabetes.

Unlike diabetic ketoacidosis, HHS produces no ketones. The condition is caused directly by very high blood glucose levels, typically greater than 600 mg/dL and often higher than 1,000 mg/dL. Without acidic ketones, there is no Kussmaul breathing and usually no abdominal distress. HHS tends to develop slowly, over days or weeks, and by the time it is apparent, the patient may already be confused or stuporous.

Both diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS are precipitated by sudden stresses that change the body’s balance of insulin and glucose. The stress can be a new illness (such as a serious infection, a heart attack, or a stroke), or the stress can be an injury. Alternately, the stress can be the addition of a new drug, such as a corticosteroid, thiazide, anticonvulsant, or sympathomimetic. Diabetic ketoacidosis, which is almost always a condition of insulin-dependent diabetics, can also develop when a patient does not take prescribed insulin.

Both conditions are emergencies and are treated in the same way. The patient is given insulin to lower the hyperglycemia and fluids to reverse the dehydration. The blood electrolyte levels are corrected, and for diabetic ketoacidosis, the pH balance of the body is shifted back toward normal. Typically, both conditions are precipitated by another recent stressor, so this problem, too, must be identified and corrected. The patient is usually monitored in an intensive care unit.

Chronic Complications

MICROSCOPIC INJURY

Because continual hyperglycemia is the cause of the chronic complications of diabetes, any reduction of average blood glucose levels (i.e., A1C values) reduces the chances of developing chronic complications. Prolonged hyperglycemia has a number of deleterious effects. Two types of microscopic cell and tissue damage seem to be involved in most of the long-term complications of diabetes (ADA, 2020l).

When there is excess glucose in the bloodstream, glucose molecules stick indiscriminately to proteins in a process called glycosylation. (For example, excess glucose binds to hemoglobin, and this is the basis of the A1C index of hyperglycemia.) Higher blood glucose levels produce more glycosylated proteins, and these glycosylated proteins tend to cross-link (bind together) into abnormal complexes. The complexes then add to atherosclerotic plaque, damage kidneys, and disrupt the structure of extracellular matrices.

Excess glucose also amplifies the amount of certain rarely produced chemicals in the body. These chemicals include sorbitol, diacylglycerol, and fructose-6-phosphate, all of which, in sufficient quantities, are detrimental to the normal functioning of cells.

Both types of molecular problems damage blood capillaries, endothelial cells of larger blood vessels, and nerves. The accumulation of these microscopic injuries leads to the macroscopic damage that produce the long-term complications of diabetes.

MACROSCOPIC INJURY

Over the years, the continual hyperglycemia of diabetes takes its toll on tissues everywhere in the body. The chronic complications of diabetes are caused by the macroscopic damage that occurs after the accumulation of 10 to 20 years of microscopic damage. In type 2 diabetes, hyperglycemia may have been present for many years before the disease is recognized. Therefore, many people with type 2 diabetes may already have macroscopic damage when they are first diagnosed (ADA, 2020l).

In the United States, the major long-term health problems from diabetes are:

- Heart disease

- Stroke

- Hypertension

- Blindness

- Kidney disease

- Nervous system disease

- Amputations

- Dental disease

- Complications of pregnancy

(ADA, 2020l)

The most common long-term complications of diabetes are damage to arteries, kidneys, eyes, nerves, and feet.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

People with type 2 diabetes develop atherosclerotic coronary artery disease more frequently than people without diabetes because elevated blood glucose levels can damage small cardiovascular blood vessels. Atherosclerosis causes myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, and insufficient circulation to the feet. Today, 80% of the people with type 2 diabetes die from some form of cardiovascular disease.

Coronary heart disease and stroke—the two predominant types of cardiovascular disease—claim the lives of almost two thirds of people with diabetes. That is 2 to 4 times higher than the rate in the general population. When people with diabetes take steps to control their blood pressure, cholesterol, and other cardiovascular risk factors, they can reduce their risk of CVD, or possibly slow its progression (Meneghini, 2020).

Patients with type 2 diabetes should be screened annually for signs, symptoms, and risk factors of cardiovascular disease. Recommendations suggest a referral to cardiology for evaluation and cardiac stress tests for patients with diabetes who also have:

- Cardiac symptoms

- An abnormal resting ECG

- Peripheral or carotid artery disease

- Autonomic neuropathy affecting the cardiovascular system

(Meneghini, 2020)

By controlling their blood glucose levels, people with type 2 diabetes reduce the likelihood of having heart and artery problems. The risk of cardiovascular disease can be reduced still further by reducing high blood pressure. In addition, aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/day) may be considered as a primary prevention strategy in those with diabetes who are at increased risk for cardiovascular problems and as a secondary prevention strategy in those with diabetes and a history of arteriosclerotic CVD. Patients and providers should have a comprehensive discussion on the benefits vs. the increased risk of bleeding (ADA, 2020f).

Hypertension

The majority of people with type 2 diabetes also develop hypertension. Individuals with diabetes are advised to keep their blood pressure below 140/90 mmHg. Lower blood pressure goals (<130/80 mmHg) should be considered for patients based on individual benefits and risks (ADA, 2020l).

Even with lifestyle changes, most people with type 2 diabetes and hypertension need antihypertensive medications (often two or more drugs) to reach this target. Patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes should also perform home monitoring of their blood pressure. Maintaining a low blood pressure may also help ward off other complications of diabetes such as vision loss and kidney failure (Meneghini, 2020).

Lifestyle therapy for hypertension treatment consists of reducing excess body weight through caloric restriction; restricting sodium intake (<2,300 mg/day); increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables (8–10 servings per day) and low-fat dairy products (2–3 servings per day); avoiding excessive alcohol consumption (no more than 2 servings per day in men and no more than 1 serving per day in women); and increasing activity levels (ADA, 2020l).

Lowering of blood pressure with regimens based on a variety of antihypertensive agents, including ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), diuretics, and calcium channel blockers, has been shown to be effective in reducing cardiovascular events (ADA, 2020e).

Lifestyle modifications and exercise programs for those patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease may benefit greatly from supervision and direction from a physical therapist and/or occupational therapist, depending on individual needs. Physical rehabilitation programs are an important component to the ongoing self-management of patients who may struggle with adding safe and appropriate physical activity to their daily routines.

Dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemia increases a person’s chances of developing cardiovascular diseases. The fasting lipid levels of people with type 2 diabetes should be screened yearly and unhealthy lipid levels treated.

In terms of reducing cardiovascular risk, the primary goal is a fasting triglyceride level of <150 mg/dL and fasting HDL cholesterol levels of >40 mg/dL in men and >50 mg/dL in women. People who already have some form of cardiovascular disease should aim for a lower LDL cholesterol level, namely <70 mg/dL (ADA, 2020e).

Statin drugs are the most effective medications for controlling total and LDL cholesterol. Patients with diabetes who are over the age of 40 should be taking a statin (even if LDL cholesterol levels are less than 100 mg/dL) and should also consider daily aspirin therapy, which can prevent the aggregation or clumping of platelets in the blood from forming clots that can block blood flow to the heart or the brain (Meneghini, 2020).

As with hypertension, the lifestyle changes recommended for treating type 2 diabetes will also improve a patient’s dyslipidemia. The addition of a statin drug is recommended for patients who do not meet the lipid target goals after changing their lifestyles. (Pregnant women should not take statins.)

Prothrombotic State

In the prothrombotic state, a condition in which the blood clots inside blood vessels more easily than normal, unnecessarily high levels of clotting molecules in the bloodstream increase a person’s risk for developing coronary artery disease and stroke. A low dose (75–162 mg/day) of enteric-coated aspirin may be recommended for some people with type 2 diabetes to help prevent cardiovascular disease. Patients with aspirin allergies, bleeding disorders, recent gastrointestinal bleeding, or liver disease should not take aspirin (ADA, 2020e; Meneghini, 2020).

DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY

Diabetic nephropathy is a common complication of diabetes. Diabetic nephropathy can progress to end-stage renal disease, and 80% of all people with end-stage renal disease have type 2 diabetes.

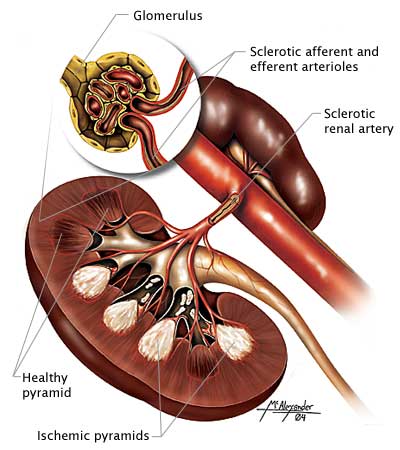

Diabetes injures those cell membranes in the kidney that are responsible for filtration and absorption of fluids and molecules. One of the earliest indicators of membrane damage is seen in the kidney glomeruli, the first of the filtration sites, which become slightly leaky and allow small amounts of protein into the urine. The small amount (30–300 mg/24 hours) of protein that abnormally appears in the urine is termed microalbuminuria.

A cross-section of the kidney showing ischemic pyramids and sclerotic arteries and arterioles. (Source: Illustration by Jason McAlexander, © Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc.)

Without treatment, the ability of the glomeruli to keep protein out of the urine declines, and eventually the person has albuminuria—the excretion of a significant amount (>300 mg/24 hours) of protein. While glomeruli are losing their ability to exclude large molecules such as proteins from the urine, they are also becoming less able to filter fluid, and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) declines. At the same time, blood pressure begins to rise.

Treatment for Diabetic Nephropathy

The American Diabetes Association (2020l) recommends that patients with type 2 diabetes check two indicators of kidney functioning annually:

- Blood should be tested for serum creatinine levels, which is used to estimate the glomerular filtration rate.

- Urine should be tested to assess albumin excretion.

In addition, blood pressure should be measured at each check-up.

By controlling all three major risk factors—blood glucose levels, blood pressure, and blood lipid levels—people with type 2 diabetes can delay the development of kidney problems. People with diabetes who already have microalbuminuria can slow its progression to diabetic nephropathy by the same interventions. When kidney problems have progressed to albuminuria and a declining GFR, it is best to consult a kidney specialist.

By itself, good control of serum glucose levels will not prevent kidney problems in people with type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, when part of a regimen that targets all the major risk factors, glycemic control does slow the onset and progression of diabetic nephropathy.

Controlling blood pressure is an effective way to delay or prevent kidney problems in people with type 2 diabetes. Hypertension accelerates the development of kidney damage as well as atherosclerosis, and all these problems feed on and worsen each other.

Some studies suggest that ARBs can delay the progression of kidney problems in people with type 2 diabetes who do not have hypertension (i.e., whose blood pressures are <130/80 mmHg) but who already have microalbuminuria. Currently, there are no agreed-upon recommendations for using either ACE inhibitors or ARBs in normotensive people (those with normal blood pressure) with type 2 diabetes.

DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

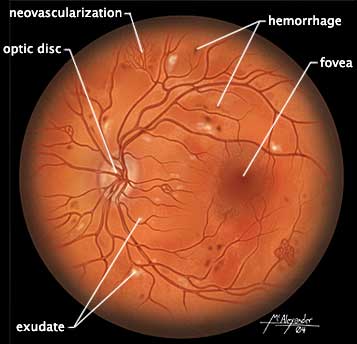

People with diabetes get cataracts earlier and with a higher frequency than people without diabetes. The most serious eye damage, however, results from long-term (>5 years) diabetic injury to capillaries and small blood vessels of the retina.

The retina viewed through a scope showing damage due to diabetes, including light exudate splotches, mini-hemorrhages, and areas of neovascularization. (Source: Illustration by Jason McAlexander. © Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc.)

Diabetic retinopathy begins with tiny aneurysms, small (“dot”) hemorrhages, and swelling of the retinal tissue. This early retinopathy leads to areas of ischemia and infarct, called cotton-wool spots. Eventually, the continuous injury causes new blood vessels to grow along the retina, accompanied by fibrous connective tissue. Once new blood vessels begin to grow (neovascularization), the problem is called proliferative diabetic retinopathy, which can later cause blindness.

For effective treatment, detecting retinal damage early is critical. People with diabetes should have a full (dilated) eye examination by an ophthalmologist or a trained optometrist when they are first diagnosed and every year thereafter (unless a less frequent schedule is recommended by an ophthalmologist). A patient with kidney damage may already have retinopathy, so kidney damage is a warning that the patient should be seen by an ophthalmologist (ADA, 2020l).

DIABETIC NEUROPATHY

Nerve damage is a common complication for people with diabetes. The damage can decrease a patient’s ability to sense actual pain, and at the same time, it can cause phantom burning pain, especially at night. Sometimes, motor nerves are affected and muscles or reflexes are weakened. When autonomic nerves are damaged, the patient can have symptoms ranging from impotence to digestive problems to dizziness on standing.

Diabetic neuropathies can take many forms. The two most common are generalized nerve injuries (called diabetic distal symmetrical polyneuropathy) and diabetic autonomic neuropathy.

Distal Symmetrical Polyneuropathy (DSPN)

Symptoms of DSPN show up at the ends of the longest nerves first. Typically, DSPN begins with unusual sensations such as tingling and numbness in the toes and feet. Over time, the paresthesias and numbness slowly move upward until they are distributed like socks on the feet, ankles, and legs. Before the problem reaches the knees, long nerves elsewhere in the body become affected, beginning at the fingers.

Eventually, the hands and lower arms have sensory reductions in a distribution like a pair of gloves. This “stocking-glove” pattern of sensory deficits is followed by decreased reflexes in the feet and ankles and by weakness in the muscles that spread the toes (Meneghini, 2020).

Autonomic Neuropathy

When diabetes damages the autonomic nerves, the symptoms vary and can affect any of the internal organs. Possible symptoms include:

- Cardiovascular: resting tachycardia (≥100 bpm), orthostatic hypotension (a drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mmHg or more upon standing), fainting, exercise intolerance

- Gastrointestinal: difficulty swallowing, slow emptying of the stomach, highly erratic or labile blood glucose levels, weak response to hypoglycemia, constipation, alternating bouts of diarrhea and constipation, nocturnal diarrhea, fecal incontinence

- Genitourinary: impotence, reduced vaginal lubrication, inability to empty the bladder, recurrent urinary tract infections

- Skin: reduced sweating of hands and feet

(ADA, 2020l; Meneghini, 2020)

Patients with type 2 diabetes are monitored for distal polyneuropathy. This is done by testing the ability of the patient to sense the vibration of a tuning fork in the toes of both feet and also the ability to sense the pressure of a standardized 10-g diabetes monofilament on the bottoms of the toes. The Achilles tendon reflexes at the ankles are checked as well as each foot for skin lesions, soft tissue injuries, and joint damage.

To screen for autonomic neuropathy, patients are assessed for the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, or skin symptoms listed above. Patients may also experience orthostatic hypotension. The resting blood pressure of patients is taken and compared with blood pressure after standing (ADA, 2020l).

By improving glycemic control, neurologic symptoms can sometimes be reduced, but there are no cures for the nerve damage of diabetes; treatments for diabetic neuropathy only alleviate symptoms. Symptoms of diabetic neuropathy are treated individually.

Poor sensation in the feet is managed by educating the patient about foot care, by limiting impact exercises, and by regular foot exams every 3–6 months. The patient may benefit from a referral to a podiatrist or advanced practice nurse specializing in managing diabetic foot care. Additional management includes referral to a physical therapist for evaluation of the extent of sensation loss, functional limitations caused by diminished balance and/or proprioception, or the need for special footwear and/or assistive devices (such as a cane or walker) when needed. An occupational therapist consultation with the patient and family to address issues inherent to the home setting and activities of daily living is also important to consider for patients with autonomic neuropathy (Meneghini, 2020).

Pain from neuropathy should be treated by a specialist, who may recommend a medication (or other regimen) appropriate to the particular patient.

Orthostatic hypotension should be evaluated by a neurologist. Therapy usually includes having the patient sleep with the head of the bed elevated, avoid sudden posture changes by sitting or standing slowly, and wear full-length elastic stockings.

Diarrhea from autonomic neuropathy should be evaluated by a GI specialist. Sometimes, the diarrhea resolves on its own, but if not, it may respond to antidiarrheal medications or to antibiotic therapy. In other cases, diarrhea can be caused by impaired neural control of sphincters and result in fecal incontinence.

Constipation can usually be treated with a stimulant laxative, such as senna.

Gastroparesis (decreased stomach motility, which delays digestion of food), bladder dysfunction, and impotence can usually be improved by medications.

FOOT PROBLEMS

It has been estimated that 20% of hospital admissions of diabetic patients are for foot problems. Over the years, damage to capillaries and small blood vessels reduces the ability of the microscopic circulation to deliver oxygen to the feet of people with diabetes. In addition, many people with diabetes develop atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, which impedes the overall circulation to their feet (Meneghini, 2020).

People with diabetic neuropathy can have muscle weakness and a poor sense of position. For these reasons, they tend to injure their feet, ankles, and legs. Any damage to their sensory nerves will make these frequent small injuries less likely to be noticed. To compound the problem, diabetic ischemia of the lower legs slows the healing of injuries and encourages infections.

Decreased sensation from peripheral neuropathy can lead to ulcers. Daily inspections are important to address small abrasions and sores before they develop into ulcers. (Source: Illustration by Jason McAlexander. © Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc.)

At each visit, the patient’s nails, skin, and joints of both of the ankles and feet are examined. Testing includes assessing the foot and ankle pulses for the ability to feel pressure and vibration and two-point discrimination to test sensation in the toes. The clinician assesses the patient as they walk, looking for uneven gait and checking shoes for uneven wear and for locations of excess pressure. The patient is asked whether they have other problems walking, such as intermittent claudication, weakness, or imbalance. Another important consideration for self-care is to determine whether the patient can safely trim toenails. A referral to a podiatrist for regular foot care and nail trimming can be very beneficial to preventing problems (Meneghini, 2020).

Patients with diabetes are warned about the extra risks that foot injuries pose for them. A physical therapist or other clinician working with a patient who has existing neuropathy or poor circulation instructs the patient and family on the proper way to inspect the feet for any injuries (e.g., with the use of a hand-held mirror) on a regular basis (ADA, 2020l). Patients are encouraged to examine their feet every day and counseled on how to care for their skin and toenails and to choose appropriate footwear. If patients have difficulty examining and caring for their feet, someone else (a family member, nurse, podiatrist, or physical therapist) is enlisted to help. Foot care is part of the initial education of all patients diagnosed with diabetes (Meneghini, 2020).

The most common cause of foot injury is excess pressure on the skin on bony prominences (such as metatarsal heads, calcaneus, and malleoli) of the feet and ankles. To ease pressure points, well-fitted athletic shoes are preferable to dress shoes or shoes with hard soles. For feet with insufficient circulation or poor sensation, special shoes with individualized internal molds may be needed in order to evenly distribute pressure during walking. Diabetic footwear includes a high, wide toe box (to maximize space and reduce pressure), removable insoles to insert orthotics if needed, and rocker soles and heel counters to provide support and stability (Physiopedia, 2020). These patients should see a podiatrist along with a physical therapist to address strategies and management to decrease injury to the feet (Meneghini, 2020).

Wounds on feet with neuropathy or poor circulation cannot be treated casually. Even small wounds must be thoroughly examined, cleaned, and debrided and re-examined daily. Patients may be unaware of pressure ulcers and other wounds, as they may have lost sensation. Antibiotics are used at the first signs of infection. Walking and other foot pressures are minimized while the wounds are healing. Soft-tissue infections must be treated aggressively with hospitalization and IV antimicrobial therapy.

When a diabetic foot becomes pale, pulseless, and painful, it is an emergency and a surgeon should be consulted.

WHAT PATIENTS NEED TO KNOW ABOUT FOOT CARE

- Cut toenails straight across and inspect the feet daily for cuts, scratches, blisters, and corns.

- Clean the feet daily with warm water and mild soap followed by thorough drying.

- Use a gentle moisturizer cream regularly (e.g., Eucerin or lanolin).

- Avoid prolonged soaking, strong chemicals (e.g., Epsom salts or iodine), and any home surgery.

- Avoid hazards such as going barefoot, extreme heat or cold, and wearing tight socks or shoes.

(ADA, 2020l; Meneghini, 2020)

AMPUTATION

At times, if a patient’s condition is not well managed, the chronic results of limb and foot problems are damaged and deformed joints and nonhealing skin ulcers. When soft tissues or bones become infected, the destruction may become severe enough to require amputation. The highest risk of amputations is in people who have had diabetes for more than 10 years and in whom microscopic tissue damage has already shown itself as eye or kidney problems (Meneghini, 2020).

The following conditions are associated with an increased risk of amputation:

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Altered biomechanics (limited mobility, bony deformities, and nail infections)

- Peripheral arterial disease

- History of nonhealing ulcers or amputations

(Cifu, 2020; Meneghini, 2020)

If a patient requires amputation, initial surgery and recovery are managed inpatient with a team approach. Rehabilitation with support from physical and occupational therapists and prosthetists during the pre- and postoperative period are vital to the patient.

Preoperative

Preoperative education goals include the following:

- Discuss the process and importance of rehabilitation after surgery.

- Describe the process of phantom pain.

- Discuss the healing process.

- Explain the process of prosthetic casting, fitting, and training.

(Cifu, 2020)

Postoperative

Postoperative rehabilitation goals include:

- Pain management

- Incisional healing

- Postoperative limb positioning and wrapping (to prevent contractures and help manage edema)

- Physical therapy:

- Bed mobility

- Transfers

- Lower extremity range of motion and strengthening

- Mobility training with appropriate assistive device (walker, wheelchair, cane, etc.)

- Balance (seated, standing, walking, stairs)

- Progressively increasing activities to tolerance

- Discharge planning (assistive device recommendations/training, home exercise program, determining need for further therapies at home, etc.)

- Occupational therapy:

- Assisting with ADLs

- Assessing need for adaptive equipment in the home

- Evaluating home safety and recommendations for modifications if needed

- Developing energy conservation strategies

- Upper extremity stretching and strengthening

(Cifu, 2020)

The goal of rehabilitation therapy after amputation is to have the patient successfully transfer back to their baseline or home environment. After surgical recovery, the patient may need to remain inpatient within a more intensive and supervised rehabilitation environment, or may be able to participate in either home-based or outpatient rehabilitation. Regardless of the rehabilitation environment upon inpatient discharge, prompt follow-up with a physical therapist, occupational therapist, and a prosthetist is important in order to continue to meet patient needs (Cifu, 2020).

The patient is assessed for the appropriate prosthetic, including a preparatory limb, after a period of wound healing has taken place. Steps to transition to a prosthetic includes assessing arm strength, balance, bed-to-chair transfers, and contralateral limb strength. Prosthetic training and exercises focus on care of skin, sock management, gait training, range of motion, stretching and strengthening, and how to manage care at home with the prosthesis (activities of daily living such as dressing, bathing, and household chores) as well as a continued program of home exercises (Cifu, 2020).

General Rehabilitation Management and Type 2 Diabetes

Patients with type 2 diabetes who have chronic, progressive complications or are recovering from procedures or medical/surgical interventions often require structured rehabilitation for a successful recovery. As discussed above, the most common chronic effects that patients with type 2 diabetes may experience include peripheral neuropathy, orthostatic hypotension, vision changes, and cardiac decompensation (Cifu, 2020).

The key to a successful rehabilitation program is individualization. Rehabilitation specialists, including physical therapists and occupational therapists, start by evaluating the patient’s baseline physical condition and any disabilities or impairments that are present either due to deconditioning or chronic effects of diabetes. The patient’s interests and motivation for improving their condition is an important component as well. Initial goal setting involves the patient and family to work toward mutual goals for progress.

ROLE OF PHYSICAL THERAPY IN REHABILITATION

Physical therapists may assist patients with diabetes in rehabilitation management through the following:

- Helping prepare a patient for the functional mobility-related aspects of surgery and recovery

- Teaching patients how to use assistive devices and/or a prosthesis

- Assessing strength, flexibility, endurance, gait, and balance (static and dynamic)

- Creating safe, individualized exercise programs to improve functional mobility, reduce pain, and improve blood glucose levels

- Assisting patients to heal and/or manage circulation and skin problems

(APTA, 2017)

Patients with type 2 diabetes may also need assistive devices to improve functional activities of daily living. They may have reduced sensation, weakness, gait disturbances, balance problems, and/or pain. Mechanical mobility aids (such as wheelchairs, walkers, or canes) may help reduce pain and lessen the impact of physical disability. Properly fitted hand or foot/ankle braces may help compensate for muscle weakness or alleviate nerve compression. Orthopedic shoes may improve gait disturbances and help prevent foot injuries in people with a loss of pain/sensation (Tabloski, 2019). Patients with neuropathy have been shown to benefit from aquatic therapy focusing on gait training, strength, and balance control (Zivi et al., 2017).

Patients with orthostatic hypotension should be advised to be proactive when changing from a supine to standing position by moving slowly and holding onto a chair or bed for 30 seconds after standing to minimize their risk for falling. Patients may also be advised to wear supportive compression stockings to increase venous return (Tabloski, 2019).

If a patient has an existing cardiac condition, gentle daily exercise to increase and maintain the ability to perform ADLs is often encouraged. These may include chair exercises, arm exercises, and other nonstrenuous movements such as tai chi or chair yoga (Tabloski, 2019).

For a patient who would like to work on increasing balance and strength, resistance exercises (such as leg extensions, chest press, and rowing); functional exercises (such as stand-sit-stand and stair climbing); and balance training (heel-toe walking, standing on one leg, etc.) may be incorporated with appropriate guidance from therapy professionals (Cifu, 2020).