LONG-TERM DIABETES MANAGEMENT

After 6 to 12 months of implementing and modifying an initial treatment plan, the frame of a long-term program takes shape. People have a schedule of regular visits with their physician and with other members of the diabetes care team. At each visit, the team reviews patient outcomes, including A1C values, daily blood glucose records, and the development and/or progression of diabetic complications, as well as offers support and help with problems in daily healthcare routines. When lab values or the clinical picture suggest the treatment routine needs to be changed, the patient meets with the healthcare team more frequently until optimal health outcomes are again stabilized.

Patient Education for Self-Management

The overall treatment plan for a person with diabetes includes a patient education program. The patient is an integral member of the treatment team and must understand and be involved in developing their particular plan.

Patient education is an entire program of its own, with trained educators who meet with the patient regularly and who are available for questions between visits (ADA, 2020g; Meneghini, 2020). The diabetes nurse educator is an important member of the healthcare team. Additionally, the Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists (ADCES) provides the names of local diabetes educators and contact information for education programs throughout the country.

PATIENT EDUCATION CORE CONTENT AREAS: ADCES SELF-CARE BEHAVIORS

- Diabetes pathophysiology and treatment options

- Healthy eating

- Physical activity

- Medication usage

- Monitoring and using patient-generated health data

- Preventing, detecting, and treating acute and chronic complications

- Problem solving

- Healthy coping with psychosocial issues and concerns

(ADCES, 2020)

HOME BLOOD GLUCOSE MONITORING

A key part of the patient education program is teaching patients how to check their blood glucose levels. Patients measure their blood glucose levels for two reasons:

- It provides a detailed record so that the healthcare team can recommend adjustments to meals, exercise, or medications.

- It gives the patient immediate feedback on how daily routines are affecting blood sugar levels.

Monitoring Frequency and Schedule

All patients with diabetes should check their blood glucose levels at a variety of times. This makes the abstract values more meaningful to the patient. It also builds a detailed record of the daily variation of glucose levels, which is especially useful while the initial treatment plan is being adjusted. Moreover, if patients watch their blood glucose levels over an extended period of time, they will learn to recognize the feeling of hypoglycemia and help to distinguish it from other uncomfortable sensations.

The frequency with which a patient checks their glucose level varies and is an individualized determination. Patients beginning insulin therapy are usually asked to monitor their blood glucose level four times a day until an optimal regimen of meals, exercise, and injections is established. After they have established a stable pattern, patients can reduce the number of blood tests as directed by their provider. Patients are advised to test their glucose level more frequently when their life pattern changes, when they get symptoms of hypoglycemia, or when they develop another illness.

Patients with type 2 diabetes who do not take insulin usually settle into a schedule of checking blood glucose levels once a day. Typically, they are asked to vary the test time so that within each week they check levels:

- First thing in the morning

- Before lunch

- Before dinner

- Before going to sleep

- 1 to 2 hours after each meal

(Nettina, 2019; ADA, 2017a)

Occasionally, patients should set an alarm and check their blood glucose level in the middle of the night. In addition, they should measure their blood glucose level when they get symptoms of hypoglycemia and when they develop another illness.

In all cases, patients should be given a target range of glucose values and told to report by telephone or email to a member of their diabetes team when home test results fall out of the prescribed goal range. Patients are also instructed to bring a log of all the interim blood glucose values to each office visit (Nettina, 2019).

Using Glucose Meters

Blood glucose meters are pocket-sized, handheld electronic devices. Most home meters measure the glucose concentration in a drop of whole capillary blood from a finger prick. (Some blood glucose meters also work with blood from other sites, such as the forearm or palm area below the thumb.) Clinical laboratories, however, measure the glucose concentration in plasma from venous blood. Glucose is about 15% more concentrated in plasma than in whole blood. The newer home meters make this correction so that the home numbers can be compared directly to the published standards.

Home testing supplies come with a variety of features, and they are changing and improving continually. The American Diabetes Association publishes an updated “Consumer Guide” in their magazine Diabetes Forecast that provides the latest updates on blood glucose testing meters and equipment, consumer health applications (apps), oral hypoglycemics, insulins, insulin delivery devices, and hypoglycemic treatments used by people with diabetes.

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) measures interstitial glucose and includes sophisticated alarms. The FDA has recently approved CGM devices to monitor glucose. CGM allows real-time glucose monitoring to make treatment decisions and is most often used for those patients who are on insulin therapy (ADA, 2020k).

ADDRESSING HYPOGLYCEMIA RISK

It is important to educate persons with type 2 diabetes who are on insulin therapy or sulfonylureas about hypoglycemia, which is a serious risk. (Hypoglycemia is defined as blood glucose <70 mg/dL.) Hypoglycemia can cause unconsciousness and, if not corrected by the addition of glucose to the bloodstream, can eventually be fatal. A very low blood glucose level (<10 mg/dL) begins causing irreversible brain damage in as little as 30 minutes.

As a rule, hypoglycemia is less of a risk for people with type 2 diabetes than for those with type 1 diabetes, but it still occurs. All diabetes patients should learn to recognize the symptoms of hypoglycemia. Initially, patients and their family members/significant others should test their blood glucose levels in different situations to compare their subjective sensations with the actual glucose levels. They should also occasionally check blood glucose levels in the middle of the night to make sure they are not getting too hypoglycemic while sleeping.

Causes and Symptoms

For people on insulin therapy, missing a meal or exercising vigorously are the most common causes of hypoglycemia. Patients with type 2 diabetes who take antisympathetic drugs, such as beta blockers, should be warned that these medications blunt the symptoms of hypoglycemia, making a potentially life-threatening situation less obvious.

Health professionals monitoring patients with type 2 diabetes must recognize the following symptoms of hypoglycemia in their patients:

- Weakness

- Shakiness

- Dizziness

- Faintness

- Feeling warm

- Sweating

- Increased heart rate

- Increased respiratory rate

- Hunger

- Headache

- Irritability

- Mood swings

- Confusion

- Pale skin

- Blurred vision

- Seizures and coma

(Merck Manual, 2019a)

Treatment

People may be instructed to treat hypoglycemia if they are experiencing symptoms even if their blood glucose is only relatively low compared to their usual readings. Sugar is the treatment for hypoglycemia.

When symptoms of hypoglycemia are experienced, persons with diabetes should:

- Test blood glucose (to determine if hypoglycemia is indeed the cause of symptoms)

- If blood glucose is low, treat using “the rule of 15,” which means, eat or drink 15 grams of fast-acting carbohydrate (i.e., 1/2 cup fruit juice or sugared soda; 4 glucose tablets; or 1 tablespoon sugar, honey or syrup), then wait 15 minutes before retesting

- If repeat test is still <100 mg/dL, treat with another 15 grams fast-acting carbohydrate (as noted above) and repeat cycle

If treatment does not improve the symptoms, the patient is directed to go to a physician, clinic, or hospital for care (Nettina, 2019).

All patients with type 2 diabetes should wear medical identification, such as a Medic-Alert bracelet. Patients may be given specific instructions about how to handle hypoglycemic episodes. Some patients should also have an emergency glucagon kit, and family and friends should be taught how and when to give a glucagon by inhalation or injection (Nettina, 2019).

Monitoring Blood Glucose Levels

An important aspect of managing type 2 diabetes is establishing blood glucose targets and monitoring blood glucose levels. Two sets of data are used to review a patient’s glycemic control: A1C values and daily blood glucose records.

The A1C values show the average level of hyperglycemia in the preceding two to three months. (See table earlier in this course to translate A1C values into average blood glucose levels.) The target for adults with diabetes is an A1C of <7%, or about 170 mg/dL. Although the ideal would be an A1C of <7%, it is difficult for most people with diabetes to get these low A1C values without having significant periods of hypoglycemia. With this in mind, less stringent goals are set for some individuals (ADA, 2020i; Meneghini, 2020).

In addition to following A1C values, the patient’s daily glucose levels are reviewed regularly. Patients whose blood glucose values are close to the targets should be re-examined every six months. Patients whose blood glucose values are out of the target range or whose medications have changed are re-examined every three months.

Monitoring for Complications

People with type 2 diabetes are at risk for developing cardiovascular disease; therefore, blood pressure and lipid profiles are monitored. Over time, elevated blood glucose can damage cardiovascular blood vessels, which in turn impedes cardiovascular blood flow and increases the risk for cardiovascular disease. Target goals for blood pressure and cholesterol are:

- Blood pressure <140/90 mmHg (less stringent goals may be set for some individuals)

- Fasting plasma HDL-cholesterol >40 mg/dL in men, >50 mg/dL in women

- Fasting plasma triglycerides <150 mg/dL

(ADA, 2020f)

The liver is the major site of the degradation of most antidiabetes drugs, including insulin. Liver dysfunction can lead to abnormally high or prolonged levels of these drugs in the blood; thus, liver function should be monitored by checking liver enzymes periodically (ADA, 2020f).

Kidney damage is a classic complication of diabetes. When the small blood vessels in the kidneys are damaged due to elevated glucose levels, the kidneys are damaged and cannot function properly. Thus, the body retains more sodium and water, and waste materials build up in the blood. Among the values to be monitored are serum creatinine levels and urine albumin levels. Estimates of glomerular filtration rates (GFR) should be calculated from the creatinine values for each individual.

At each visit, the patient’s feet should be assessed for tissue or joint damage and the ability of the feet to sense stimuli.

The blood vessels of the retina in patients with diabetes can be injured because of elevated blood glucose levels. This increases the risk for eye problems in these patients. People with diabetes therefore need regular eye exams to check for glaucoma, cataracts, and retinal damage. An annual dilated-eye examination provides the best information about the health of each eye and an indication of total vascular health (ADA, 2020f).

Long-Term Exercise Management

For exercise to have a substantial role in treating diabetes, the activities must be regular and long-term. Therefore, exercise must fit realistically into the patient’s life. Duration and frequency of exercise is important in order to improve and maintain glycemic control along with weight management. Patients with diabetes should perform aerobic and resistance exercise regularly. Aerobic activity should last at least 10 minutes, with the goal of 30 minutes/day or more on most days of the week with no more than two consecutive days without exercise (ADA, 2020f; Meneghini, 2020).

Many patients with type 2 diabetes have lived sedentary lives before the time of their diagnosis. For this group of patients, an exercise schedule begins gradually, with short, regular walks or brief exercise sessions according to individual tolerance. Over time, the length and intensity of the exercise sessions are increased. Depending on each patient’s individual functional status and exercise needs, progress may be monitored by an exercise physiologist, physical therapist, and/or occupational therapist.

EXERCISE AND BLOOD GLUCOSE MONITORING

Depending on their medication regimen, persons with type 2 diabetes may need to monitor their blood glucose levels to assess for any fluctuations that occur with exercise. About 30 minutes after exercise begins, most people’s blood glucose level rises, then it begins to fall. Many things affect blood glucose levels during exercise:

- Fitness level of individual

- Time of day

- Type of exercise/activity

- Prevailing glucose level prior to exercise

- Duration and intensity of exercise

The patient is instructed to monitor blood glucose levels and plan according to the following recommendations:

- Check blood glucose before exercise and every one to two hours during exercise.

- Check blood glucose again after exercise to see how exercise affects glucose levels. This is beneficial in planning for future exercise and whether medication adjustment or carbohydrate intake is needed.

- Always have a carbohydrate food or drink available during exercise.

- If blood glucose was within the goal range before exercise and it falls more than 30–50 mg/dL or hypoglycemia occurs, eat one carbohydrate serving (15 grams) every 30–60 minutes during exercise.

- The effect of exercise on glucose levels can last for several hours after activity; be prepared for the possibility of delayed hypoglycemia.

- If rapid, short, or intermediate-acting insulin is being used as treatment, it may be necessary to decrease the dose of insulin taken prior to exercise by 10%–30% (long-acting insulin is not generally adjusted for exercise) as directed by the primary care provider.

- Whenever possible, exercise should be planned for times when insulin is not peaking.

(ADA, 2020f)

Patients should not exercise:

- If blood glucose level is >300 mg/dL. Postpone exercise until it is <300 mg/dL.

- If blood glucose is <70 mg/dL. Eat one or two carbohydrate servings and make sure the blood glucose level is back in goal before starting exercise.

- When feeling ill.

- Prior to bedtime. This reduces the risk of hypoglycemia during the night. If evening exercise is necessary, patients may be instructed to take an extra carbohydrate serving before bed and wake up during the night to test blood glucose.

(ADA, 2020f)

EXERCISE PRECAUTIONS AND DIABETIC COMPLICATIONS

The diabetes team screens each person for health problems that must be accommodated in the exercise program. Very few problems preclude adding more physical activity to the daily life of a person with diabetes, but certain problems put special constraints on those activities.

Cardiovascular disease. Before a sedentary patient with diabetes and cardiovascular risks starts a new exercise program, the patient undergoes a medical exam, including a stress test to assess cardiac function. This may not be needed for young, otherwise healthy people with diabetes. If the test shows cardiovascular problems, it is still possible to create a gradually increasing exercise plan, with the patient warned not to overexert and to watch for symptoms of angina, including chest, jaw, or arm tightness or pain and palpitations or shortness of breath (ADA, 2020g).

Hypertension. The general rule is to bring a patient’s blood pressure into a healthy range before initiating an exercise program (ADA, 2020g).

Retinopathy. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (damage to the retina) or severe nonproliferative retinopathy puts a patient at risk for vitreous hemorrhages or retinal detachment. There is controversy over whether vigorous exercise can cause these problems, therefore the patient should be examined by a retinal ophthalmologist before adding exercise into the management plan for those with diabetic retinopathy (ADA, 2020g).

Peripheral neuropathy. A patient who lacks the ability to fully sense injury to the feet, ankles, and legs can damage skin and joints without realizing it. Peripheral neuropathy can also often affect balance and equilibrium. Therefore, diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy may benefit from working closely with a physical therapist or exercise physiologist to incorporate an individualized plan of care for rehabilitation that is appropriate for their specific situation. Patients with significant peripheral neuropathy should not participate in strenuous exercise such as prolonged walking, treadmill use, jogging, or step exercise unless specifically instructed and monitored by an appropriate healthcare professional (ADA, 2020g).

Autonomic neuropathy. Damage to the autonomic nervous system can cause reduced or inappropriate responses to exercise. Patients with diabetes who have autonomic neuropathy are given a thorough cardiac examination before beginning a new exercise program (ADA, 2020g).

CASE

Alessandro is a 53-year-old male patient who is being treated for newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. He has been referred for an initial evaluation with a physical therapist due to several recent falls that occurred at the factory where he is employed.

In the initial patient interview, Alessandro states that he has fallen on the job at least five times during the past six months. Two falls occurred when he tripped over a large wooden crate and three occurred when he may have tripped on something but “wasn’t sure what.” In addition to describing the falls, Alessandro also complains of slight numbness, tingling, and decreased sensation in his feet over the past several months. He states that he has not exercised regularly for over ten years but that he previously enjoyed playing basketball and golf.

Alessandro tells the therapist that he understands the importance of overall fitness in helping him to best manage his diabetes and that he would like to be able to be more active in the sports he used to enjoy. He states that he has been hesitant to participate in sports, however, due to fear of falling. Alessandro describes his goals for physical therapy as being able to perform his job without fear of falling and to find meaningful and enjoyable fitness activities for himself.

The physical therapist completes an initial evaluation of his functional status, which reveals the following pertinent objective information about Alessandro:

- Range of motion and manual muscle testing within functional limits for upper and lower extremities

- Berg Balance score of 37/56, indicating significant compromise of static and dynamic balance

- Ability to stand on his right foot for 7 seconds without losing balance and on his left foot for 3 seconds before losing balance

- Ability to maintain Romberg position for approximately 25 seconds before losing balance

- Inability to maintain sharpened Romberg position without external support

- Decreased proprioception at both ankles and diminished two-point discrimination on the plantar surfaces of both feet

- Frequent loss of balance when attempting to walk on uneven or soft surfaces

Together, the physical therapist and Alessandro develop the following goals to address both his current functional deficits and his long-term personal objectives:

Short-Term Goals

- Alessandro will be independent and compliant with a home exercise program that addresses static and dynamic balance, skin inspections to both feet, and proprioceptive activities.

- Alessandro will improve his Berg Balance score by at least 3 points.

Long-Term Goals

- Alessandro will demonstrate a Berg Balance score of 49 or above to ensure that he is safe with independent ambulation and at minimal risk of falling.

- Alessandro will demonstrate consistently safe ambulation over all surfaces (including soft, uneven, or sloped surfaces) without loss of balance.

- Alessandro will successfully navigate his work environment without loss of balance or falls for a period of 30 days.

- Alessandro will be independent and active in a long-term plan of preferred fitness activities for which he has been medically cleared for participation (such as swimming, water polo, walking, or cycling) in order to optimize his overall activity and fitness level as a component to helping him most effectively manage his medical condition.

The physical therapist recommends a plan of care to include outpatient physical therapy two times weekly for a period of four to six weeks in order to address static and dynamic balance training, proprioceptive activities, training in foot inspections, workplace and community safety awareness training, and structuring and tailoring of an overall, long-term fitness plan.

Long-Term Nutrition Management

The American Diabetes Association and the American Dietetic Association make available many detailed recommendations about healthy eating for people with diabetes. Frequently, however, it is necessary for diabetes educators to translate the recommendations into terms that are practical and understandable for individual patients. For this task, a diabetes treatment team needs trained dietitians or nutritionists.

For all types of diabetes, a fundamental part of treatment is controlling the composition and quantity of meals. People with type 2 diabetes who take fixed doses of insulin or insulin secretagogues schedule their meals and their medications to avoid periods of hypo- and hyperglycemia.

The priority for meal planning is striking a healthy balance that minimizes hyperglycemia, encourages weight loss (when needed), reduces dyslipidemia, and lowers blood pressure. These goals can be accomplished when the person’s meals have reduced calories, low-saturated and trans fat, low cholesterol, and low amounts of sodium, with an appropriate overall mix of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. Detailed carbohydrate counting of each meal is not necessary (Franz & Evert, 2017).

The Mediterranean, low-carbohydrate, and vegetarian/plant-based diets are all examples of healthy eating that have shown positive results in research. Individualized meal planning should focus on personal preferences, needs, and goals. Reducing overall carbohydrate intake for patients with diabetes has the most evidence for improving glycemia control (ADA, 2020g).

The Diabetes Plate Method is often taught to individuals managing type 2 diabetes. This method provides a visual way to plan a meal of healthy vegetables, lean proteins, and limited higher carbohydrate foods that can cause a spike in blood glucose.

THE DIABETES PLATE METHOD

(Source: CDC.gov)

Start with a 9-inch dinner plate:

- Fill half with nonstarchy vegetables, such as salad, green beans, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, and carrots.

- Fill one quarter with a lean protein, such as chicken, turkey, beans, fish, or eggs.

- Fill one quarter with a grain or starchy food, such as potatoes, rice, or pasta.

(Hamilton, 2015)

Patients with type 2 diabetes not meeting glycemic targets or for whom reducing glucose-lowering drugs is a priority, reducing overall carbohydrate intake with a low- or very-low-carbohydrate eating plan may be an option to try. There is no exact mix of nutrients that comprises the optimal diet for people with type 2 diabetes. The recommended balance for all healthy adults is also one of the best guides for people with diabetes (ADA, 2020g).

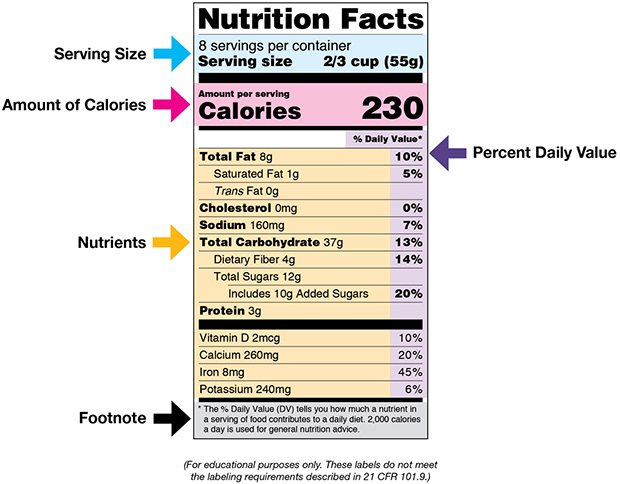

HOW TO READ FOOD LABELS

The “Nutrition Facts” label is required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on most packaged foods and beverages. The label provides detailed information about a food’s nutrient content, such as the total amount of calories, serving size, and amount and kinds of fat, added sugar, sodium, fiber, and other nutrients. Knowing how to read food labels is especially important for patients with diabetes who need to follow a special diet. It also makes it easier to compare similar foods to decide which is a healthier choice.

(Source: U.S. Food and Drug Administration.)

The following tips can help patients with diabetes read and understand food labels:

- Start by reading the serving size and the number of servings in the package. Serving sizes are standard, making it easier to compare similar foods. Serving sizes are usually listed in common terms, such as cups or pieces, as well as in metric amount (e.g., grams).

- Next review the calories. This section provides information on how much energy (in calories) is provided in the food.

- The following section of the label contains information about specific nutrients. Nutrients listed in the first section are those that may need to be limited (e.g., fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, or sodium). Listed next, total carbohydrates are a key component, and patients should understand their goals for total carbohydrates for each meal and decide the portion size to match. Nutrients listed in the last part of this section are important to include in a balanced diet (e.g., dietary fiber, vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron).

- The right-hand column and footnote area of the label provide information on Daily Values (DVs) for each nutrient listed and are based on public health experts’ advice. DVs are recommended levels of intakes. DVs in the footnote are based on a 2,000-calorie diet.

(U.S. FDA, 2020)

CARBOHYDRATES

A person with diabetes should include a healthy balance of carbohydrates in their meal plan each day. Although low-carbohydrate diets might seem to be a logical approach to lowering blood glucose levels after a meal, foods containing carbohydrates are important sources of energy, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and low-fat milk are all recommended. Foods with whole grains have been shown to reduce insulin sensitivity (ADA, 2020g).

Carbohydrate intake should be based on each individual patient’s lifestyle, medications, BMI, and level of activity. Patients who are very active will be able to have higher carbohydrate intake than those patients who are not active or who are active on a weight-loss plan. A general guideline for an adult woman is to limit carbohydrates intake to 30–45 grams for each of three meals per day and adult men to limit carbohydrate intake to 45–60 grams for each of three meals per day (ADA, 2020g; Franz & Evert, 2017).

| Recommend | Limit |

|---|---|

| (ADA, 2020g) | |

|

|

Glycemic Index

The glycemic index is a standard way to compare the effects of different foods on the blood glucose level after a meal. Foods with a lower glycemic index cause less of a spike in blood glucose after they are eaten. Low–glycemic index foods include oats, barley, bulgur, beans, lentils, legumes, pasta, pumpernickel (coarse rye) bread, apples, oranges, milk, yogurt, and ice cream. Theoretically, these foods should make blood glucose control easier for people with diabetes; in reality, studies show that diets with low–glycemic index foods make glycemic control only slightly easier than diets with high–glycemic index foods (Franz & Evert, 2017).

Carbohydrate Counting

Limiting the intake of excessive carbohydrates in the diet is a key part of controlling hyperglycemia. When regular doses of insulin or insulin secretagogues are needed to manage the glucose load after meals, it is important for patients to match the dose to the amount of carbohydrates that are eaten at each meal. Patients can estimate the carbohydrates in their meals by summing the approximate grams in each serving. The labels of most foods help patients to make these estimates (ADA, 2017b).

Carbohydrate counting may be done in one of two ways:

- The person takes a fixed dose of insulin at each meal and tries to eat a fixed, predetermined amount of carbohydrates that coincide with that amount of insulin.

- The person has an insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR) in which they count the carbohydrates they are going to consume and calculate the amount of insulin to take based on the ICR.

(ADA, 2017b)

FATS

Dietary fats contribute to the total calories consumed, but the amount of fat in a meal has only a small effect on the level of blood glucose after the meal. The more important consideration for people with type 2 diabetes is their risk for developing coronary heart disease. Dietary fats play a major role in the formation of atherosclerotic plaque. To reduce the likelihood of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, a person—especially, a person with type 2 diabetes—should limit saturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol in meals (ADA, 2020g; Franz & Evert, 2017).

Fats should make up 20%–35% of a person’s total daily calories. Saturated fats should be limited to less than 7% of total daily calories, trans fats minimized, and cholesterol limited to less than 200 mg per day. Most of the daily fat intake should be monounsaturated or polyunsaturated (a “Mediterranean” diet) (Franz & Evert, 2017).

| Recommend | Limit |

|---|---|

|

|

Plant sterols and stanols (types of natural vegetable fats) can lower blood cholesterol levels and are good substitutes for other fats (Franz & Evert, 2017). To increase the sterols and stanols in the diet, patients can replace other types of fat with commercial margarine spreads (e.g., Benecol, Take Control) or dietary supplement capsules (e.g., Benecol Softgels, Cholest-Off, Cholesterol Success Plus).

PROTEIN

As with fats, proteins in a meal do not significantly raise after-meal glucose levels. Proteins (actually, the amino acids derived from the proteins) do increase insulin secretion, and in this way, eating protein with carbohydrates helps a person with type 2 diabetes to reduce the spike of blood glucose after a meal. For the same reason, however, proteins are not good snacks for preventing the hypoglycemia of vigorous exercise or hypoglycemic episodes in the middle of the night.

In a healthy diet, proteins should contribute about 15%–20% of a day’s total calories (Franz & Evert, 2017). Plant-based proteins are a good source of healthy protein and fats as well as a good source of fiber. Some research has found successful management of type 2 diabetes with meal plans that include slightly higher levels of protein (20%–30%), which may contribute to increased satiety (ADA, 2020g).

| Recommend | Limit |

|---|---|

|

|

FIBER

Some plant carbohydrates—such as cellulose, gums, and pectin—cannot be broken down and digested by humans. These are called dietary fiber. Insoluble dietary fiber, such as cellulose (e.g., bran), speeds the movement of food through the digestive tract. Soluble dietary fiber, such as gums and pectin (e.g., oatmeal), slows the rate of absorption of digestible nutrients. A high quantity of soluble fiber in a patient’s diet can reduce blood cholesterol and can modestly reduce hyperglycemia and insulin resistance.

The recommendation for the general public is 14 grams of fiber for every 1,000 calories in a person’s everyday diet. For people with diabetes, the recommendation is higher—a total of 50 grams of fiber per day, regardless of the total daily calories. Plants contain dietary fiber. Legumes, cereals with ≥5 g fiber/serving, fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain products are recommended (Franz & Evert, 2017).

MICRONUTRIENTS

As with the general population, people with diabetes need sufficient vitamins and minerals in their diets to meet the body’s daily needs. Poorly controlled diabetes or weight-loss diets can cause nutritional deficiencies, and the minimum daily vitamin and mineral needs may require the patient to take daily supplements. Other people with diabetes who may need supplements are older adults, pregnant women, lactating women, and strict vegetarians (Franz & Evert, 2017).

Vitamin B12 levels may be monitored in those patients who are taking metformin since B12 deficiency can occur in these patients (Aroda et al., 2016). Some clinicians may recommend that patients with type 2 diabetes take a daily supplement of 0.4–1.0 mg folic acid, 0.4 mg vitamin B12, and 10 mg pyroxidine (Franz & Evert, 2017).

BEVERAGES

High-calorie beverages should be replaced by no-calorie or artificially sweetened drinks. Most fruit juices contain more sugar than people realize, and juices should not be drunk by people with diabetes merely to quench their thirst.

Drinking high amounts of alcohol brings a host of health problems, including an increased risk for developing diabetes (ADA, 2020g). People with diabetes who choose to drink alcohol should drink only moderately. Generally speaking, moderate drinking means no more than two drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women.

Mixed drinks can also contain significant amounts of carbohydrates, so people with diabetes should pay attention to the content of their drinks. It is also best for those who drink alcohol to do so with food, especially at night, in order to avoid a later episode of hypoglycemia.

Alcohol should not be drunk by women who are pregnant or by people with liver disease, pancreatitis, advanced neuropathy, or very high levels of blood triglycerides (Franz & Evert, 2017).

According to the ADA, moderate alcohol consumption does not have major detrimental effects on long-term blood glucose control in people with diabetes. However, risks associated with alcohol consumption include hypoglycemia, weight gain, and hyperglycemia (ADA, 2020g).

DIABETES DISTRESS

Diabetes distress is a common and distinct concern for patients with diabetes. Diabetes distress is described as significant negative psychological reaction related to the emotional burden and stress a patient with diabetes may experience as a result of having to manage a severe and complicated chronic disease. Patients are dealing with multiple lifestyle and behavioral demands, including medication dosing and titration, monitoring blood glucose, food intake, and physical activity. This constant pressure to manage their condition may cause more and more distress as the disease progresses. Patients often feel guilt and distress if their condition worsens despite making lifestyle changes and taking medications.

Providers should routinely screen patients for distress using validated measures. If distress is identified, appropriate referral for additional support (social, emotional, and financial) and education may be recommended as well as a referral to a mental health provider for assessment and management (ADA, 2020f).