RISK ASSESSMENT

The purpose of assessing the risk for developing pressure injuries is to implement early detection and prevention measures. This is of utmost importance, as assessment without intervention is meaningless.

Risk Factors for Pressure Injuries

Certain groups of patients have a higher risk for developing pressure injuries. These include patients who:

- Are older adults (those over age 65 are at high risk and those over age 75 are at even greater risk)

- Are in critical care

- Have a fractured hip (which indicates increased risk for heel pressure injuries)

- Have spinal cord injuries (spasticity, the extent of the paralysis, a younger age at onset, difficulty with practicing good skin care, and a delay in seeking treatment or implementing preventive measures increase the risk of skin breakdown)

- Have diabetes, secondary to complications from peripheral neuropathy

- Are confined to a wheelchair or bed

- Are immobile or for whom moving requires significant or taxing effort (i.e., morbidly obese)

- Experience incontinence

- Have neuromuscular and progressive neurological diseases (e.g., multiple sclerosis, ALS, Myasthenia gravis, stroke)

- Have neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, dementia)

Changes in both skin structure and function due to aging contribute to the occurrence of skin problems and decrease wound healing.

- A flattening of the epidermal-dermal junction decreases the overall strength of the skin, which increases the risk for skin tears and blistering.

- A decrease in the melanocytes and Langerhans cells increases the risk for allergic reactions and sensitivity to sunlight.

- A decrease in fibroblast function increases the time required to synthesize collagen.

- A decrease in blood flow decreases skin temperature and delays healing.

- A decrease in oil and sweat production contributes to dryness and flaking.

- A decrease in subcutaneous tissue, especially fat, decreases the body’s natural insulation and padding.

- A decline in the reproduction of the outermost layer of the epidermis may lead to the skin’s inability to absorb topical medications.

These changes in skin structure and function (together with changes in cellular DNA that affect cell reproduction and the ability to protect the skin) and the risks that occur with a change in overall health and functional ability put an aged patient at very high risk for the formation of a pressure injury (WOCN, 2016b; EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

More than 100 additional risk factors associated with the development a pressure injury have been identified. Some of these include:

- General medical conditions, such as diabetes, stroke, multiple sclerosis, cognitive impairment, cardiopulmonary disease, cancer, hemodynamic instability (abnormal/unstable blood pressure), peripheral vascular disease, malnutrition, and dehydration

- Smoking

- History of a previous pressure injury (since scar tissue is weaker than the skin it replaced and will break down more easily than intact skin)

- Increased facility length of stay

- Undergoing surgery longer than four hours

- Significant weight loss

- Prolonged time on a stretcher (since the surface is not conducive to pressure relief)

- Emergency department stays

- Medications, such as sedatives, analgesics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Impaired sensation

- Refusal of care, such as when a patient refuses to be turned or moved despite education

- Edema

- Obesity

- Patient not being turned

- An ICU stay, due to the high acuity of illness, presence of multiple comorbid conditions, and:

- Mechanical ventilation

- Vasopressors and hemodynamic instability

- Multiple surgeries

- Increased length of stay

- Inability to report discomfort

(WOCN, 2016a; EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019)

Risk Assessment Schedules

The skin is the largest organ in the body, and the clinician must assess it regularly. The assessment of pressure injury risk is performed upon a patient’s entry to a healthcare setting and repeated on a regularly scheduled basis (per facility policy) as well as when there is a significant change in the patient’s condition, such as surgery or a decline in health status (WOCN, 2016a; EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

A schedule for reassessing risk is established based on the acuity of the patient and an awareness of when pressure injuries occur in a particular clinical setting. Recommendations based on the healthcare setting are included below (WOCN, 2016a; EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019). A particular facility or setting may have different regulations.

Across all settings the three groups most at risk for pressure injuries are:

- Individuals over 65 years of age

- Neonates and children younger than three

- Individuals of any age with spinal cord injury

ACUTE CARE

Generally, pressure injuries can develop within the first two weeks of hospitalization, and elderly patients can develop pressure injuries within the first week of hospitalization. The initial assessment is conducted upon admission and repeated:

- At least every 24 to 48 hours

- Whenever the patient is transferred from one unit to another

- Whenever the patient’s condition changes or deteriorates

- Per facility policy

Most medical-surgical units reassess daily.

ICU/CRITICAL CARE

ICU patients are at high risk for developing pressure injuries, especially on the heel. ICU patients have been shown to develop pressure injuries within 72 hours of admission. Pressure injuries have been associated with a two- to fourfold increase in the risk of death in older people in the ICU. Pressure injury assessment is to be done at least once every 24 hours (WOCN, 2016b; EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

One study of 84 ICU patients found that over 30 days, 33 patients developed pressure injuries and seven of the pressure injuries were medical device–related. Another study demonstrated that mean arterial pressure and positive end-expiratory pressure in ICU patients on a mechanical ventilator can be contributing factors to the risk of developing pressure injury. The importance of carefully monitoring hemodynamic parameters in ICU patients, particularly mean arterial pressure, and carefully deciding on the most appropriate positive end-expiratory pressure for these patients was emphasized as a mechanism to decrease the occurrence of pressure injuries (Soodmand, 2019).

INPATIENT REHABILITATION SETTINGS

Studies in this area showed that 1.4% of patients developed a new or worsening pressure injury during their stay. The presence of a pressure injury was significantly associated with lower gains in motor function, longer length of stay, and decreased odds of being discharged to the community. Assessment is on admission and per facility protocol.

LONG-TERM CARE

In long-term care settings, most pressure injuries develop within the first four weeks.

- In skilled nursing facilities, the initial assessment is conducted upon admission and repeated weekly thereafter.

- In nursing homes with long-term patients, the assessment is conducted upon admission, repeated weekly for the first month, and repeated monthly thereafter, or whenever the patient’s condition changes.

HOME HEALTH

In home healthcare settings, most pressure injuries develop within the first four weeks.

The initial assessment is conducted upon admission and repeated:

- At resumption of care

- Recertification (assessment and approval of the need for continuation of patient care)

- Transfer or discharge

- Whenever the patient’s condition changes

Some agencies reassess with each nursing visit.

HOSPICE AND PALLIATIVE CARE

One study showed that of eight pressure injuries that developed during the study, five occurred within two weeks prior to death. Assessment occurs at admission and as patient condition changes.

Elements of an Assessment

Prevention of pressure injuries must begin with frequent and routine assessment of the patient’s skin and of the risk factors that, if left unmanaged, will contribute to the development of an injury. Risk assessment without interventions to modify the risk is meaningless.

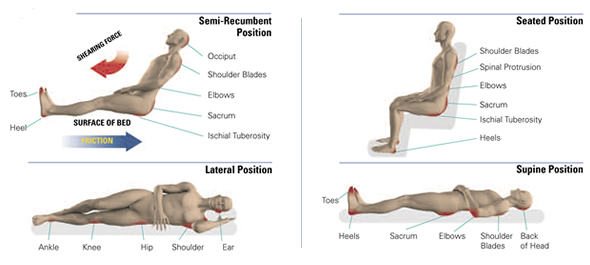

A head-to-toe inspection of the skin must be done on admission and at least daily (or per facility regulation). Five parameters for skin assessment are recommended by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, including skin color, skin temperature, skin texture/turgor, skin integrity, and moisture status (WOCN, 2016a). The assessment should focus on high-risk areas such as bony prominences, areas of redness, and under medical devices. The specific areas to assess are shown in the table and diagram below.

| If the patient’s position is: | Then focus on these areas: |

|---|---|

| Lateral | Ear, shoulder, trochanter, knee, ankle |

| Supine | Occiput, shoulder blades, elbows, sacrum, heels, toes |

| Semi-recumbent | Occiput, shoulder blades, elbows, sacrum, ischial tuberosities, heels |

| Seated | Shoulder blades, spinal protrusions, elbows, sacrum, ischial tuberosities, heels |

Bony prominences are high-risk areas for pressure injuries. (Source: © Invacare Corporation. Used with permission.)

Blanchable erythema is a reddened area that temporarily turns white or pale when pressure is applied with a fingertip. This is an early indication to redistribute pressure. Nonblanchable erythema is redness that persists when fingertip pressure is applied. It means that tissue damage has already occurred. (See “Stage 1 Pressure Injury” later in this course for images of blanchable and nonblanchable erythema.)

It can be difficult to identify skin problems in patients with dark skin. Redness may not be easy to see. The clinician needs to compare the at-risk area (such as the coccyx or hip) with skin next to it and look for color differences or changes in temperature or pain.

ASSESSMENT AND MEDICAL DEVICES

Medical devices such as shoes, heel and elbow protectors, splints, oxygen tubing, face masks, endotracheal tube holders, compression stockings and TED hose, and others must be removed and the skin inspected daily. For example, oxygen tubing can cause pressure injuries on the ears, and compression stockings and TED hose have been known to cause heel injuries.

If the device cannot be removed—such as a nasogastric (NG) tube, urinary catheter, tracheostomy holder, neck brace, or cast—then the skin around the device must be carefully inspected: the nares for an NG tube, the neck for a tracheostomy, the mucosa for a urinary catheter, etc. If the patient complains of pain under an unremovable device, notify the physician.

Consider all adults with medical devices to be at risk for pressure injuries.

- The Joint Commission’s Quick Safety issue on the management of medical device–related pressure injuries (MDRPI) states that almost every hospital patient needs at least the use of one medical device during their stay, which puts them at risk for pressure injury (Camacho-Del Rio, 2018).

- Between 50%–90% of pressure injuries in the pediatric population are MDRPIs. In the pediatric population, MDRPIs include injuries caused by central lines, endotracheal tubes, feeding tubes, pulse oximetry monitors, tracheostomy appliances, and respiratory equipment. Studies indicate the majority of MDPRIs result from the use of respiratory equipment (Boyar, 2019a).

- A recent international study of MDPRIs in adult patients found that the most common sites are the ears and feet. Over 30% of MDPRIs were associated with nasal oxygen tubing, with injury to the ears and nose (Kayser, 2018).

Injuries caused by medical devices are reportable to state and federal agencies, just as are those caused by pressure on bony prominences (EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

ASSESSMENT AND MOBILITY

Immobility is the most significant risk factor for pressure injury development. More frequent monitoring to prevent pressure injuries is conducted for patients who have some degree of immobility, including those who are:

- Nonambulatory

- Confined to bed, chairs, wheelchairs, recliners, or couches for long periods of time

- Paralyzed and/or have contractures

- Wearing orthopedic devices that limit function and range of motion

- Dependent on assistance to ambulate or reposition themselves

ASSESSMENT FOR FRICTION VS. SHEARING

Friction is the rubbing of one surface against another. Patients who cannot lift themselves during repositioning and transferring are at high risk for friction injuries. Friction may contribute to the development or worsening of a pressure injury due to the shear it creates. There are two types of friction:

- Static friction is the force that resists motion when there is no sliding; for example, static friction prevents an individual from sliding down in bed when the head of the bed is elevated.

- Dynamic friction is the force between two surfaces when there is sliding, for example, when a person is sliding down in bed. Skin trauma can result.

Shear is the mechanical force that is parallel to the skin and can damage deep tissues such as muscle. Shear can result when friction stretches the top layers of skin as it slides against a surface, or deeper layers when tissues attached to the bone are pulled in one direction while the surface tissues remain stationary.

Shearing most commonly occurs when the head of the bed is elevated above 30 degrees and the patient slides downward. Friction is most common when patients are turned or pulled up in bed (WOCN, 2016a; EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

ASSESSMENT FOR INCONTINENCE

Moisture from incontinence can contribute to pressure injury development by macerating the skin and increasing friction injuries. Fecal incontinence is an even greater risk for pressure injury development than urinary incontinence because the stool contains bacteria and enzymes that are caustic to the skin. When both urinary and fecal incontinence occur, the fecal enzymes convert the urea in the urine to ammonia, which raises the skin’s pH. When the skin pH is elevated (alkaline), the skin is more susceptible to damage. Pressure injuries are four times more likely to develop in patients who are incontinent than in those who are continent (WOCN, 2016a).

ASSESSMENT FOR NUTRITIONAL STATUS

Although individual nutrients and their specific roles in preventing pressure injury have not been determined, malnutrition is associated with overall morbidity and mortality. A nutritional assessment should be conducted upon admission or when there is a change in the patient’s condition that would increase the risk of malnutrition, such as:

- Patient’s refusal to eat or eating less than usual

- Prolonged NPO status

- Development of a wound or other conditions that increase metabolic demand

- When a pressure injury is not progressing toward healing

The clinician must also keep in mind that overweight and obese patients can be malnourished and should undergo a nutritional assessment.

Parameters to assess include:

- Current and usual weight

- History of unintentional weight loss or gain

- Food intake

- Dental health

- Ability to swallow and/or feed oneself

- Medical interventions (such as surgeries of the gastrointestinal tract that may affect absorption of nutrients such as vitamin B12)

- Psychosocial factors (such as the ability to obtain and pay for food)

- Cultural influences on food selection

Serum albumin and prealbumin are no longer considered reliable indicators of nutritional status, as there are multiple factors that will decrease albumin levels even with adequate protein intake. These include inflammation, stress, surgery, hydration, insulin, and renal function. Therefore, laboratory evaluation should be only one part of a nutrition assessment (WOCN, 2016a; Bryant & Nix, 2016; Shah, 2018).

CASE

Mr. Frank is a 90-year-old man who has been admitted to the hospital with pneumonia. He fell at home three months ago and was also hospitalized at that time. His equally elderly wife denies that she is having any difficulty caring for him and says that he eats well and takes all his medications.

The admitting nurse finds Mr. Frank to be very thin and that he weighs 10 pounds less than when he was hospitalized after his fall. His incontinence brief is saturated with urine, and his perineal skin is raw. He does not move himself in the bed. The nurse recognizes that Mr. Frank is at high risk for developing a pressure injury due to his poor nutrition, his immobility, and his incontinence. The nurse discusses with the physician the patient’s need for a dietitian referral, a pressure reduction mattress, and a barrier product to protect his skin. She alerts the discharge planner that Mr. Frank may also require home health, with personal care services daily if that is available with his insurance coverage.

The physician also requests a physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) evaluation and recommendations to improve the patient’s mobility and self-care needs in order to reduce his risk for developing a pressure injury. Prior to discharge, a physical therapist and occupational therapist assess and work with Mr. Frank, as well as providing pertinent education and hands-on training for Mrs. Frank in order to optimize her ability to safely care for her husband at home.

For instance, the physical therapist begins to teach Mrs. Frank how to safely assist her husband with bed mobility, transfers to/from a bedside chair and/or commode, and ambulating short distances with a rolling walker. The occupational therapist teaches Mrs. Frank how to safely assist her husband with ADLs (such as dressing, bathing, and toileting). Both therapists recommend continued PT and OT services in the home setting in order to progress the patient’s functional mobility and independence with ADLs.

If Mr. Frank and his wife continue to have difficulty with his care at home, nursing home placement will need to be considered.

Determining Risk Levels

Several risk assessment tools or scales are available to help predict the risk of a pressure injury, based primarily on those assessments mentioned above. These tools consist of several categories, with scores that when added together determine the total risk score.

The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk is the most popular, widely used risk assessment tool in use today for predicting pressure injuries. It was first published in 1987 and has thus been in use for about 30 years across a variety of settings. Two other common scales are the Norton Scale and the Waterloo Scale (WOCN, 2016d). The clinician uses these tools to help determine risk so that interventions can be started promptly.

These tools are only used for assessing adults. The Braden-Q Scale has subcategories that relate to assessing children.

It is important that when the clinician uses a scale, the scale must not be altered in any way, meaning there cannot be shortcuts or changes to the definitions. Any changes would alter the accuracy and usefulness of the scale in predicting the risk of developing pressure injuries. The same scale should be used consistently throughout the facility, and if this this not a standard practice, it is one that clinicians should advocate for.

Assessment tools notwithstanding, if a patient has other major risk factors present (such as age, fever, poor perfusion, etc.), the patient may be at higher risk than a risk score would indicate. Clinicians should work to assure that, regardless of the specific risk assessment tool being used, the professionals using it are proficient in its use and knowledgeable regarding potential risk factors within their patient population that are not accounted for in the assessment tool they are using (WOCN, 2016b).

BRADEN SCALE

The Braden Scale consists of six categories:

- Sensory perception: Can the patient respond to pressure-related discomfort?

- Moisture: What is the patient’s degree of exposure to incontinence, sweat, and drainage?

- Activity: What is the patient’s degree of physical activity?

- Mobility: Is the patient able to change and control body position?

- Nutrition: How much does the patient eat?

- Friction/shear: How much sliding/dragging does the patient undergo?

There are four subcategories in each of the first five categories and three subcategories in the last category. The scores in each of the subcategories are added together to calculate a total score, which ranges from 6 to 23. The higher the patient’s score, the lower their risk.

- Less than mild risk: ≥19

- Mild risk: 15–18

- Moderate risk: 13–14

- High risk: 10–12

- Very high risk: ≤9

It is recommended that if other risk factors are present (such as age, fever, poor protein intake, hemodynamic instability), the risk level be advanced to the next level. Each deficit that is found when using the tool should be individually addressed, even if the total score is above 18. The best care occurs when the scale is used in conjunction with nursing judgment. Some patients will have high scores and still have risk factors that must be addressed, whereas others with low scores may be reasonably expected to recover so rapidly that those factors need not be addressed (WOCN, 2016b).

(See also “Resources” at the end of this course.)

NORTON SCALE

The very first pressure injury risk evaluation scale, called the Norton Scale, was created in 1962 and is still in use today in some facilities. It consists of five categories:

- Physical condition

- Mental condition

- Activity

- Mobility

- Incontinence

Each category is rated from 1 to 4, with a possible total score ranging from 5 to 20. A score of less than 14 indicates a high risk of pressure injury development.

WATERLOO SCALE

The Waterloo Scale, mainly used in Europe, was developed in 1987. This scale consists of seven items:

- Weight for height

- Skin type

- Sex and age

- Malnutrition screening tool

- Continence

- Mobility

- Special risk factors

Potential scores range from 1 to 64. The tool identifies three categories of risk: at risk (score of 10–14), high risk (score of 15–19), very high risk (score of 20 and above).

Of the three tools described above, the Braden Scale is the most validated pressure injury risk assessment tool, and it is the most widely used assessment tool in the United States (Shah, 2018; Baranoski & Ayello, 2016). In a study comparing the Braden and Waterloo tools, it was found that the Braden Scale took less time to administer and addressed risk factors that are more objective. Data from the study put the reliability of the Braden Scale at 83% and that of the Waterloo Scale at 40% (Solati, 2016).

THERMAL IMAGING TO DETECT DEEP TISSUE INJURY

Research has shown that changes in temperature frequently occur before there are changes in skin color. Thermal imaging has therefore become an established tool in the assessment of deep tissue pressure injury (DTPI). Human skin produces infrared radiation, which allows long-wave infrared thermography (thermal imaging) to detect changes in skin temperature. It has been found that alterations in skin color related to unrelieved pressure more often develop into a pressure injury when the temperature of the area at baseline is below that of the adjacent skin.

In a study of 114 patients in an ICU, thermal imaging was used along with clinical assessment to evaluate anatomical sites at high risk for DTPIs, namely, the coccyx, sacrum, and bilateral heels. Thermal assessments were performed using the Scout Device, which is FDA approved for this procedure. Detecting early changes in skin temperature before there were any visible signs of DTPI allowed for proactive interventions, and data from the study demonstrated about a 60% reduction in the number of DTPIs compared to the unit’s usual rate.

Study authors pointed out that thermal imaging can result in significant cost savings, reduced expenditure in treating pressure injury, and reduced settlements related to legal liability for hospital-acquired pressure injury. Clinicians require training in the correct use of thermal injury equipment (Koerner, 2019).